Takayasu's disease (Takayasu syndrome, aortic arch syndrome, nonspecific aortoarteritis) is a granulomatous inflammation of the aorta and its large branches and their stenosis. The disease was first described by Japanese ophthalmologist Mikito Takayasu in 1908. The disease mainly affects women. The average age of cases in Europe reaches 41 years, in Japan - 29, in India - 24. It is most common in Japan, Southeast Asia, India and Mexico. There are no exact data on the prevalence in Russia. In children, the disease has a more acute and aggressive course.

Story

In the first descriptions, nonspecific aortoarteritis was called “pulseless disease” - because due to obliteration of the large branches of the aorta, patients often had no pulse in the upper extremities.

Before the official discovery, the most similar disease was described by the professor of anatomy at the University of Padua Giovanni Batista Morgagni (1682–1771) in 1761: in a woman aged about forty years, an autopsy revealed dilation of the proximal part of the aorta in combination with stenosis of the distal parts, the inner layer of the aorta was yellow in color and contained calcifications. During life, the patient had no pulse in the radial arteries.

In 1839, British military doctor James Davy described another similar case. A 55-year-old soldier at the age of 49 developed pain in his left shoulder, and four years later the pulse in his hand weakened, for which he consulted a doctor. A year later, the man suddenly died; an autopsy revealed a large rupture of the aortic arch aneurysm and complete occlusion of the vessels extending from the aortic arch.

In 1854 in London, surgeon William Savory (1826–1895) also reported a disease very similar to Takayasu's disease. In a 22-year-old woman, no pulse was detected in the vessels of the neck, head and upper extremities for five years; seizures began to occur during the course of the disease, and the patient died. An autopsy revealed thickening and narrowing of the aorta and arch vessels - they felt like a thick rope to the touch, there were no aneurysms.

Finally, in 1908, the Japanese ophthalmologist Makito Takayasu, at the Twelfth Annual Conference of the Japanese Society of Ophthalmology, reported on two annular anastomoses around the optic disc in a young woman without pulses in the peripheral arteries. These were arteriolovenular shunts. In addition, the blood vessels surrounding the optic disc were slightly elevated. Japanese colleagues associated changes in retinal vessels with the absence of pulses in the patient’s radial arteries.

Pulselessness syndrome has been called by many names, leading to confusion. It was only in 1954 that Japanese doctors William Caccamise and Kunio Okuda introduced the term “Takayasu disease” (TD) into the English literature.

1.General information

Takayasu aortoarteritis (Takayasu disease, Takayasu syndrome, nonspecific aortoarteritis, sometimes in web sources you can also find the erroneous spelling “Takayasu arthritis”) is a granulomatous inflammatory process that affects large blood vessels, namely the arteries of the main aorta. Interestingly, this disease was first mentioned and described by ophthalmologists (it was named after its discoverer) more than a hundred years ago - as an unusual inflammation of the retinal vessels.

Today, Takayasu's disease is considered one of the rarest diseases, but by all criteria it is precisely a disease, a pathological process with certain patterns, and not sporadic unsystematic accidents. The frequency of occurrence is, according to various estimates, 1-4 people per million; Despite great difficulties in collecting the necessary statistics, it has been reliably established that women get sick approximately eight times more often than men, and the most common age of manifestation varies between 15-40 years.

A must read! Help with treatment and hospitalization!

Etiology and pathogenesis of Takayasu syndrome

Most often, the cause of BT cannot be determined; a connection with tuberculosis and streptococcal infections is assumed. There is evidence of an increased frequency of a number of histocompatibility antigens in patients in various populations:

- India - HLA B5, B21;

- USA - HLADR4, MB3;

- Japan - HLADR2, MB1, Bw52, DW2, DQW1 HLA Bw52‑CAD, AR, HLA B39.

Autoimmune mechanisms play a certain role in the pathogenesis: there is an increase in the level of IgG and IgA and fixation of immunoglobulins in the wall of the affected vessels. Also characteristic are changes in the cellular component of immunity and disturbances in the rheological properties of blood with the development of chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome.

The course of Takayasu disease (TD) has a certain stage. At an early stage of the disease or during exacerbations, nonspecific symptoms of systemic inflammation occur. During this period, up to 10% of patients do not have any complaints at all. As it progresses, there is inflammation of the vessel walls and the development of stenosis, which almost always occurs, even in patients with aneurysms. Bilateral vascular stenosis predominates.

Clinical picture: symptoms of Takayasu's disease

In the acute stage, patients are most often bothered by nonspecific symptoms of systemic inflammation. These are fever, night sweats, malaise, weight loss, joint and muscle pain, and moderate anemia. But already at this stage there may be signs of vascular insufficiency, especially in the upper extremities - absence of pulse. The absence of a pulse or a decrease in its filling and tension in one of the arms, asymmetry of systolic blood pressure in the brachial arteries is recorded in 15–20% of cases. Much more often, in 40% of cases, patients complain of a feeling of weakness, fatigue and pain in the muscles of the forearm and shoulder, often unilateral, aggravated by physical activity. At this stage, BT is diagnosed extremely rarely.

The chronic stage, or the full picture stage, begins after 6–8 years. Symptoms of damage to the arteries extending from the aortic arch predominate due to the progression of inflammation of the vessel walls and the development of stenosis, usually bilateral. Even in the presence of an aneurysm, in almost all cases there is also stenosis. As stenosis progresses, symptoms of ischemia of individual organs appear. Vascular inflammation can occur without systemic inflammatory reactions, then pain is observed at the site of projection of the affected vessel or tenderness upon palpation.

On the affected side, increased fatigue of the arm develops during exercise, its coldness, a feeling of numbness and paresthesia, the gradual development of atrophy of the muscles of the shoulder girdle and neck, weakening or disappearance of the arterial pulse, a decrease in blood pressure, in 70% - a systolic murmur is heard in the common carotid arteries. 7–15% of patients experience neck pain, dizziness, transient moments of visual impairment, shortness of breath and palpitations, and 15% of patients experience pain on palpation of the common carotid arteries (carotidynia).

During this period, compared with the early stage of the disease, symptoms of vascular insufficiency of the upper extremities and intermittent claudication, damage to the cardiovascular system, brain and lungs are much more common (50–70%).

Damage to internal organs

In the chronic stage, symptoms sometimes appear due to damage to the arteries arising from the abdominal aorta, most often with anatomical types II and III of the disease. Vasorenal arterial hypertension of a malignant course, attacks of “abdominal toad” caused by damage to the mesenteric arteries, intestinal dyspepsia and malabsorption may develop.

Clinical signs of lung damage (chest pain, shortness of breath, nonproductive cough, rarely hemoptysis) are observed in less than a quarter of patients.

Damage to the coronary arteries occurs in ¾ of patients, in 90% of cases the mouths of the coronary vessels are affected, and the distal parts are rarely affected. Damage to the ascending aorta is often described - compaction combined with dilatation and the formation of aneurysms. Arterial hypertension occurs in 35–50% of cases and can be caused by involvement of the renal arteries or the development of glomerulonephritis, less often by the formation of coarctation of the aorta or ischemia of the vasomotor center against the background of carotid vasculitis. As a result of arterial hypertension, coronaryitis and aortic regurgitation, chronic heart failure develops.

Anatomical variants of Takayasu's disease:

Type I - the lesion is limited to the aortic arch and its branches (8% of patients); Type II - the descending part (thoracic and abdominal sections) of the aorta is affected (11%); Type III (mixed) - the most common, includes damage to the aortic arch and its descending section (65%); Type IV - includes lesions characteristic of the first three options in combination with arteritis of the branches of the pulmonary artery; occlusion of the brachial and iliac arteries, damage to the aortic arch and renal arteries is also observed (Takayasu-Denerey syndrome, 16%).

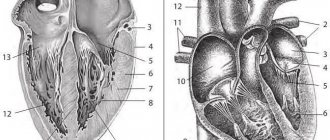

Pathomorphology

In the chronic phase, the aorta is thickened due to fibrosis of all three layers of the vessel. The lumen often narrows in several places. If the disease progresses quickly, fibrosis does not have time to lead to the formation of an aneurysm. The intima may be ribbed, with a “tree-bark” appearance; this feature is characteristic of many aortoarteritis. These changes usually occur in the aortic arch and its branches, but the thoracic and abdominal parts of the aorta and their corresponding branches may be involved in the process.

Recent studies of the cellular composition of the aortic walls have shown that the formation of new vessels occurs in the deep intima associated with the adventitia. T cells and dendritic cells are also observed in the vascular environment, with small numbers of B cells, granulocytes and macrophages. Inflammation is most noticeable in the adventitia, with infiltration of B and T cells.

As a result, ischemia, hypertension, and atherosclerosis develop. With a slow course, there is a pronounced development of collateral circulation.

Takayasu arteritis

Takayasu arteritis is a well-known but rather rare form of large vessel vasculitis. As with any rare disease, randomized controlled clinical trials are either absent or conducted on a small number of patients, which does not allow full conclusions to be drawn.

Takayasu arteritis, also known as pulseless disease, occlusive thromboaortopathy, and Martorell syndrome, is a chronic inflammation of the arteries primarily affecting large vessels, primarily the aorta and its main branches. Inflammation of the blood vessels leads to thickening, fibrosis, stenosis of the wall and, as a result, to the formation of blood clots. Manifested by symptoms of limb ischemia. More acute inflammation can lead to the formation of an aneurysm. Previously it was believed that the disease only affected women from East Asia, but now it is clear that both women and men can get sick. The sex ratio appears to decrease from East Asia to the West.

The first description of this pathology was published in 1830. Yamamoto described the case of a 45-year-old man with persistent fever, weight loss, shortness of breath, and absent pulses in the upper extremities and carotid artery. In 1905, Takayasu, professor of ophthalmology at Kanazawa University, Japan, presented a case of a 21-year-old woman with characteristic arteriovenous anastomoses. The same year, Onishi and Kagosha described similar cases involving absent pulses in the wrist. In 1920, the first postmortem case of a 25-year-old woman demonstrated panarteritis, leading to the theory that changes in the fundus were due to retinal ischemia. It was not until 1951 that Shimizu and Sano summarized the clinical features of this “pulseless disease.”

Takayasu arteritis is most commonly seen in Japan, Southeast Asia, India, and Mexico. It was listed as an incurable disease in 1990, and patients suffering from this disease are supported by the Japanese government, where 5,000 such patients have been registered to date. The clinical picture ranges from asymptomatic disease detected by pulse examination to catastrophic neurological impairment. A hypothesis has been proposed of a two-stage disease process with a “pulseless phase”, characterized by nonspecific inflammation, followed by a chronic phase with the development of vascular insufficiency, in some cases accompanied by repeated outbreaks of inflammation.

People usually get sick in the 2nd-3rd decade of life; from the moment the first symptoms appear until diagnosis is made, it takes from several months to several years. In one large study, 80% of patients were between 11 and 30 years of age, 77% between 10 and 20 years, and the time of symptom onset to diagnosis was between 2 and 11 years in 78% of cases. Nonspecific symptoms include fever, night sweats, malaise, weight loss, arthralgia, myalgia, and mild anemia. As inflammation progresses and stenoses develop, the clinical picture due to the development of collateral circulation comes to the fore. Stenotic lesions predominate and tend to be bilateral. Almost all patients with aneurysms also have stenoses, and in most of them the vascular lesions were widespread.

Characteristic symptoms:

- In 84-96% of cases, there is a weakened or absent pulse associated with lameness.

- Vascular murmurs are present in 80-94% of patients; several arteries are often affected, especially the carotid, subclavian and abdominal vessels.

- Hypertension in 33-83% of patients is usually a consequence of renal artery stenosis, which is observed in 28-75% of patients.

- Takayasu retinopathy occurs in 37% of cases.

- Aortic regurgitation due to dilatation of the ascending aorta, divergence and thickening of the valve leaflets in 20-24%.

- Congestive heart failure associated with hypertension, aortic regurgitation and dilated cardiomyopathy.

- Neurological symptoms due to hypertension and/or ischemia, including postural dizziness, seizures and amaurosis.

- Pulmonary artery involvement occurs in a wide range of 14-100% of cases, depending on the method of examining the pulmonary vessels.

- Pulmonary artery involvement has only a slight correlation with the systemic nature of the involvement, but this feature may be useful in the differential diagnosis.

- Other symptoms include shortness of breath, headaches, carotidynia, myocardial ischemia, chest pain and erythema nodosum.

Symptoms can be quite variable: for example, Japanese patients, predominantly female (96%), had dizziness, lack of pulsation, longer and more severe inflammation and aortic regurgitation. This is in contrast to Indian patients, 37% of whom were male. They usually complained of headache, had hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy due to vasculitis of the abdominal aorta and renal vessels. Nevertheless, the majority of patients in both countries had diffuse arterial disease.

Of the most characteristic clinical manifestations of Takayasu's arteritis, the American College of Rheumatology defined specific diagnostic criteria in 1990 (Table 1).

Table 1 | American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria. At least 3 of 6 criteria are required to make a diagnosis.

In diagnosis, angiography remains the gold standard (Fig. 1, 2). Evaluation of the pulmonary vasculature by angiography is not recommended routinely and is indicated for symptoms of pulmonary hypertension.

Figure 1 | Aortogram of the aortic arch. Damage to all extracranial vessels.

Figure 2 | Aortogram of the aortic arch. (A) severely narrowed right common carotid artery, (B) occlusion of the left common carotid artery, and (C) proximal stenosis of the left subclavian artery. (D) The right vertebral artery provides the main supply to the brain.

Doppler ultrasound is a useful non-invasive method for assessing vessel wall inflammation. Because of the vascular involvement, histologic examination is usually not helpful unless patients undergo revascularization procedures.

Differential diagnosis includes other causes of large vessel vasculitis: inflammatory aortitis (syphilis, tuberculosis, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, Behcet's disease, Kawasaki disease and giant cell arteritis); developmental abnormalities (aortic coarctation and Marfan syndrome) and other aortic lesions such as ergotism and neurofibromatosis. Most of them have specific symptoms that allow them to be diagnosed, although tuberculosis still poses a problem in terms of differential diagnosis, being a possible etiological factor. Although tuberculous aortitis tends to cause erosion of the vessel wall to form true or false aneurysms, most commonly affecting the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta, and causing dissection and rupture as complications rather than the stenoses that are typical of Takayasu arteritis. The incidence of complications such as rupture and bleeding in Takayasu aneurysmal arteritis is low. Syphilis tends to affect older age groups, with calcification of the descending thoracic aorta, although it is not characterized by stenosis.

An attempt was made to classify the disease based on angiographic findings. A new classification of Takayasu arteritis has been proposed (Table 2).

Table 2 | Angiographic classification of Takayasu Arteritis.

This system is useful in that it allows the patient's characteristics to be correlated according to vascular involvement, which is important in surgical planning, although it is not particularly helpful in terms of prognosis. The normal course of any disease can only be established in the absence of specific treatment. Ishikawa defined clinical groups based on the natural history of the disease and its complications. The four most important complications were identified: Takayasu retinopathy, secondary hypertension, aortic regurgitation, and aneurysm formation. Each of them is rated as moderate, moderate or severe, which allowed us to describe four degrees of disease (Table 3).

Table 3 | New classification of Takayasu arteritis proposed by Ishikawa.

In the chronic phase, macroscopically, the aorta is thickened due to fibrosis of all three layers of the vessel wall. The lumen is narrowed unevenly, often affecting several areas. If fibrosis progresses rapidly, it can lead to subsequent aneurysm formation. The intima may become deformed, with the appearance of the “tree bark” symptom, characteristic of many aortitis. Microscopically, an acute inflammatory phase can be distinguished, resulting in fibrosis. In the acute phase, inflammation of the vessels feeding the vessels is observed in the adventitia. The media is infiltrated with lymphocytes and single giant cells. Mucopolysaccharides, smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts thicken the intima. In the chronic phase, fibrosis occurs with the destruction of elastic tissue. Similar histopathological findings are also observed in giant cell arteritis, making it impossible to differentiate between these vasculitis based on biopsy results.

A recent study of the cellular composition of the aortic wall showed newly formed vessels in the intima associated with the adventitial vasa vasorum. The vessels were surrounded by T cells, dendritic cells, with some B cells, granulocytes and macrophages. The media contained acellular fibrous tissue with foci of neovascularization and single smooth muscle cells. Inflammation was most pronounced in the adventitia infiltrated by B and T cells. In half of the cases, nodes are formed in the immediate vicinity of the antigen represented by dendritic cells, with a central location of B lymphocytes and peripheral T lymphocytes. Granulocytes were located outside these nodes.

Infection has also been shown to be involved in the pathogenesis. The role of tuberculosis is especially noted due to its high prevalence in patients with Takayasu arteritis, which is especially evident in endemic areas. Viral etiology is also being investigated as a trigger for vasculitis. γδT cells, αβT cells (CD4 and CD8) and natural killer cells play an important role in vascular damage. Heat shock protein, to which γδT cells respond, is found in high abundance in the aortic tissue of patients with Takayasu's arteritis, and limited expression of the αβT cell receptor VαVβ gene indicates activation against a specific antigen. This is also supported by reports of limited expression of VγVδ genes in γδT cells and the synthesis of various costimulatory molecules necessary for T cell activation.

Takayasu arteritis is also associated with different human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles. Some alleles have specific epitopes that may be important as a factor in susceptibility to disease, which is interpreted by some scientists as an argument in favor of an autoimmune process. However, no specific autoantigens have yet been found, and for any adaptive immune response against an exogenous or endogenous antigen, presentation of the antigen to T cells by the major histocompatibility complex is a central event.

A study published in 1998 concluded that no known serological test could establish the phase of the disease with vascular pathology. Several studies have examined the acute phase response in Takayasu arteritis. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated in 29 of 54 patients. Higher values were observed in younger patients and decreased with age, possibly representing the natural history of the disease. However, later researchers came to the conclusion that ESR is not a reliable marker of the course of the disease, which led to a further search for better serological markers, which was not successful. Markers assessed included ESR, C-reactive protein, tissue factor, von Willebrand factor, thrombomodulin, and tissue plasminogen activator, in addition to various adhesion molecules.

Although disease activity cannot be determined from these markers, for some patients, testing them over time may be helpful. The concentrations of pro-inflammatory and chemotactic cytokines interleukin 1β, IL-6 and cytokine A5 (RANTES) were assessed using ELISA. All subjects had elevated IL-6 and RANTES concentrations during active disease compared to healthy controls. These cytokines correlated with ESR, but not with CRP. This phenomenon has not been explained. Positive correlation with disease activity suggested that these cytokines may contribute to the development of vasculitis, but serum cytokine levels are not necessarily a reflection of tissue cytokine concentrations.

Treatment

Steroids are the mainstay of treatment for Takayasu's arteritis, although reports of effectiveness vary. Early data suggested little benefit, with six of eight patients showing no improvement. Data from the United States in 1985 demonstrated a decrease in ESR, a decrease in the activity of inflammatory symptoms, and in 8 of 16 patients with pulselessness, its restoration occurred. In more recent studies, remission was achieved at least once with steroids alone in 60%. Today it is estimated that approximately half of patients receiving steroids will respond to treatment. These results led to a further search for more effective treatment.

Comparisons were attempted with treatments for other systemic vasculitides such as Wegener's granulomatosis. Immunosuppressants tested included cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and methotrexate. However, the difficulty in comparing Takayasu's arteritis with Wegener's granulomatosis relates not only to the size of the vessel affected by the disease process, but also to the very different morbidity and mortality. Untreated systemic Wegener's granulomatosis has a 1-year mortality rate of 82%, which is in sharp contrast to that of Takayasu's arteritis. A study was conducted in 25 steroid-refractory patients who received cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or methotrexate, although not at the same time. The overall remission rate was 33% versus 23% who did not achieve it.

Because no single cytotoxic drug was superior to any other in terms of effectiveness, side effects were factors in determining treatment. Methotrexate has previously been reported to be clinically effective and well tolerated. Subsequent studies showed good response to therapy including methotrexate and steroids. There are also data from treatment of three patients with mycophenolate mofetil. All three responded well, no toxicity was observed, and steroids were limited or discontinued. However, larger studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Indications for surgical treatment include hypertension with critical renal artery stenosis, cerebrovascular ischemia or critical stenoses of three or more cerebral vessels, moderate aortic regurgitation and coronary artery disease with confirmed coronary artery disease. Radical surgical treatment of thoracic aneurysms is recommended if technically possible, although such procedures do not prevent recurrence of aneurysms.

Sources

Johnston SL, Lock RJ, Gompels MM Takayasu arteritis: a review //Journal of clinical pathology. – 2002.

Treatment of nonspecific aortoarteritis

Taking steroid medications is the main treatment for Takayasu's disease. Data on its effectiveness vary, which may be related to the stage of the disease. Data obtained in the USA in 1985 showed that in six out of 29 patients, steroid treatment led to a decrease in ESR, inflammatory symptoms. Eight of the 16 patients with absent pulses experienced their return after a delay of several months. Later (1994) American studies showed that remission was achieved in 60% of cases (out of 48 patients).

It is now generally accepted that approximately half of patients treated with steroids experience improvement. The lack of universal treatment and the side effects associated with steroid use have led to the search for more effective treatments.

As with other systemic vasculitides, immunosuppressive drugs can be used, including cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and methotrexate. American researchers in 1994, using the example of 25 patients who were not amenable to treatment with steroid drugs, showed that taking cytostatic drugs (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine or methotrexate) leads to remission in 33% (Takayasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:919– 29).

Since methotrexate is easily tolerated, its effectiveness in combination with steroids was further studied. Thirteen of 16 study participants with aortic arch syndrome taking methotrexate (81%) experienced remission. However, 7 of them experienced relapses when they completely stopped taking steroid drugs. Ultimately, eight patients experienced sustained remission for four to 34 months, and four of them were able to stop treatment completely. In three of the 16, the disease progressed despite treatment.

Thus, about a quarter of patients with active disease do not respond to current treatments.

Complications

Aortic arch syndrome can vary in severity. In some people, the disease is mild and is not accompanied by complications. However, in other cases, prolonged or repeated cycles of arterial inflammation and healing can lead to one or more of the following:

Reduced elasticity and narrowing of blood vessels, which can lead to a decrease in blood supply to organs and tissues. Arterial hypertension, which usually develops as a result of decreased blood supply to the kidneys. An inflammatory process in the heart that can affect the heart muscle (myocardium), the heart valves (valvulitis) or the sac around the heart (pericarditis). Heart failure due to hypertension, myocarditis, or aortic regurgitation—a condition characterized by blood leaking back into the heart due to a leaky aortic valve—or a combination of these conditions. Ischemic stroke is a type of stroke that occurs when blood flow in the arteries leading to the brain is reduced or blocked. Transient ischemic attack, a temporary disorder of cerebral circulation, the symptoms of which are identical to those of an ischemic stroke, but does not cause long-term damage. An aortic aneurysm, which occurs when the walls of a blood vessel weaken and bulge, forming a bulge in the vessel that can rupture. A heart attack (myocardial infarction) is an uncharacteristic phenomenon that can develop as a result of a decrease in blood supply to the heart. Damage to the lungs when the disease develops in the arteries leading to the lungs (pulmonary arteries) Pregnancy

In women with aortic arch syndrome, uncomplicated pregnancy is possible. However, the disease can negatively affect a woman's reproductive ability and the course of pregnancy. If you have aortic arch syndrome and are planning a pregnancy, it is important to work out a detailed action plan with your doctor before becoming pregnant to prevent possible complications. In addition, during pregnancy it is necessary to be under close medical supervision.

Surgery

It is advisable to perform surgical intervention on the aorta and great vessels in the first five years after diagnosis.

- Endarterectomy is indicated for small occlusions.

- Bypass surgery with special prostheses is performed when the lesion is large.

Indications for surgery are determined by the extent of the process and the degree of obstruction of peripheral vessels. Surgery is performed outside the active stage of BT.

Clinical example

A 13-year-old girl was admitted to the pediatric department on the referral of a cardiologist with complaints of headaches, nosebleeds, and increased blood pressure to 220/110 mm.

rt. Art. She did not suffer from childhood infections. Vaccinated according to age up to three years. From the age of nine she was in a boarding school (her mother and father abused alcohol and were deprived of parental rights). At the age of ten, myopia was detected (wears glasses). For the last two years, the child has been under the care of her aunt, who considers the girl sick since she was nine years old, when the above-described complaints appeared. Upon admission to the department, the girl’s condition was of moderate severity, the child had an asthenic build and poor nutrition. During auscultation of the heart, a systolic murmur is heard at the V point. The liver is 1 cm below the edge of the costal arch, blood pressure is at the level of 180–150/85–80.

The hemogram shows slight neutrophilia, ESR - 43 mm/h. In a biochemical blood test, C-reactive protein was elevated, the rest was without pathology, antistreptolysin-O and rheumatoid factor were not detected. Coagulogram - decreased prothrombin index. ECG without pathology. EchoCG revealed moderate hypertrophy of the interventricular septum and posterior wall of the left ventricle, left-sided aortic arch, narrowing of the aorta in a typical location to 5–6 mm. According to CT/MRI, there are signs of Takayasu's disease (type IV): intimal detachment of the ascending aorta with transition to the arch, segmental stenosis of the thoracic descending aorta, damage to long segments of the great vessels of the brain, CT data in favor of segmental narrowing of the left renal artery.

Metipred and methotrexan were prescribed. Symptomatic therapy included aspirin, atenolol, chimes, and captopril. During therapy, regression of general inflammatory signs was noted, but hypertension could not be completely suppressed. Three months later, the dose of metipred was increased, antihypertensive therapy was adjusted, but the pressure remained high. Taking into account the nature of vascular damage (type IV), the unstable and partial anti-inflammatory effect of the therapy, in this case the prognosis for life is very unfavorable.

Adapted from: Okhotnikova E.N. et al.: Takayasu’s disease (nonspecific aortoarteritis) is a fatal systemic vasculitis in children. "Clinical immunology. Allergology. Infectology", No. 2, 2011.

Why us?

- Qualified help. In our hospital, doctors conduct examinations using high-precision, expert-class equipment. Therapy is prescribed in accordance with international treatment standards. Provide comprehensive recommendations for nonspecific aortoarteritis e.

- Convenient accommodation. The diagnostic complex and therapeutic departments are located in the same building, so you will spend a minimum of time on examination and consultation.

- Confidentiality. Our employees strictly adhere to the principle of medical confidentiality, so you do not have to worry about disclosing information about your health.

- Comfortable conditions. Our rheumatologists devote maximum time to each client. If surgery is necessary, you will be provided with a comfortable room in our hospital.

Modern medicine in the vast majority of cases makes it possible to reduce risks and improve the quality of life in this complex disease, subject to early diagnosis. At the slightest suspicion of nonspecific aortoarteritis, make an appointment with a rheumatologist at the Yauza Clinical Hospital to identify the disease in time and begin treatment.

You can see prices for services

Exodus

The 5- to 10-year survival rate for Takayasu disease is about 80%, and the five-month to one-year survival rate is close to 100%. The most common cause of death is stroke (50%) and myocardial infarction (about 25%), less often - rupture of an aortic aneurysm (5%). With damage to the coronary arteries in the first two years from the onset of symptoms of cardiac pathology, mortality reaches 56%. An unfavorable prognosis in patients whose disease is complicated by retinopathy, arterial hypertension, aortic insufficiency and aortic aneurysm. Patients with two or more of these syndromes have a 10-year survival rate from diagnosis of 59%, with most deaths occurring in the first five years of the disease.

Contraindications to surgery for aortoarteritis are the acute period of myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic renal failure, sepsis, diabetes mellitus and obliteration of distal vessels.

2. Reasons

For a long time, the causes of aortic-arterial inflammation remained completely unclear. Today, most experts are inclined to believe that Takayasu’s arteritis is one of the autoimmune rheumatoid diseases in which the body’s defense system begins to attack and tries to destroy its own cells, recognizing them as foreign. However, this hypothesis, for all its validity (the obvious clinical and pathomorphological similarity with diseases of this type is also confirmed by laboratory results), also explains little, since science still does not have a clear and comprehensive answer to the main question: why, in fact, does it start? autoimmune attack and why in different cases it targets different organs - in particular, the walls of the blood supplying arteries, as in this case.

Visit our Rheumatology page