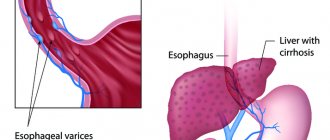

Causes of esophageal varicose veins

The disease develops against the background of increased pressure in the portal vein (also known as the portal vein), but other pathologies (hypertension, congenital anomalies, and so on) can contribute to its occurrence. Esophageal varicose veins, the causes of which lie in pathological changes in the portal vein, often begin to progress with previously diagnosed severe diseases of the liver or pancreas - cirrhosis, tumors, insufficiency. The disease often develops against the background of severe diseases of the thyroid gland, in which case we will be talking about pathological disorders of the vena cava.

According to statistics, esophageal varicose veins are more often diagnosed in men aged 50 years and older.

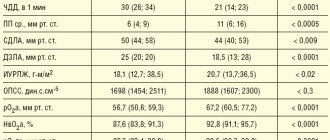

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF PORTAL HYPERTENSION

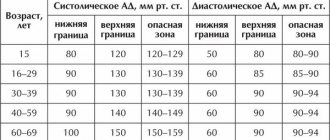

With physical examination, it is easiest to detect ascites, redness, spider-like angiomas on the skin, erythema pubis, testicular atrophy, gynecomastia, Dupuytren's contracture and muscle atrophy. Portosystemic encephalopathy may also manifest itself - in some cases, asterixis (blurring or “purrying” tremor of the hands) and lethargy, in the lungs - restlessness, sleep disturbance. Most patients with PG also exhibit splenomegaly, although the size of the spleen correlates poorly with portal venous pressure and its increase may be associated with other illnesses. A hyperdynamic state can be indicated by a high (jumping) pulse, warm, well-perfused endings in conjunction with arterial hypotension.

Signs of portosystemic collaterals are dilated veins on the anterior surface of the abdomen (umbilical-epigastric shunts), the “jellyfish head” becomes a sinuous colateral vein near the navel. Internal hemorrhoids are not a specific finding, but may also manifest collateralization. The weakness of the visible collateral vessels on the back does not indicate portal hypertension, but obstruction in the level of the inferior venous vein. A rare cause may be compression of the lower empty vein by regenerative nodes in liver cirrhosis.

Ascites is easy to detect when there is a lot of swelling in the stomach - in such cases the life is tight, and swelling of the spine can be detected. However, minor ascites can be diagnosed instrumentally, for example, with the help of ultrasonography. Paracentesis helps to establish the etiology of ascites: the portal (non-peritoneal) etiology indicates a serum ascitic albumin gradient (SAAG) of over 1.1 g/dL (11 g/L). However, this method cannot distinguish between hepatic and suprahepatic PH, for example, in cases of persistent heart failure. Recent studies indicate a decrease in SAAG following the placement of transjugular portosystemic shunts (TIPS).

Laboratory testing of gas is not specific for the detection of PG. Indicates an increase in prothrombin hour and thrombocytopenia. In patients with cirrhosis of the liver, these indicators are considered predictors of the presence of varicose veins (see below). Hypoalbuminemia indicates the importance of liver function and, indirectly, PG. Similarly, hyponatremia and low sodium concentrations in the tissue may contribute to water and sodium retention in portal hypertensive syndrome.

Esophageal varicose veins: symptoms

Depending on the degree of development, the following signs are distinguished:

- First degree. The diameter of the veins is increased by no more than 3 mm, the formation of single nodes is possible. Diagnosis of the disease is possible only by the endoscopic method; there are no clinical signs.

- Second degree. A rather dangerous period of varicose veins of the esophagus - there are no symptoms (even the mucous membrane of the organ still remains unchanged), but at the same time the contour of the veins already becomes unclear, and X-ray diagnostics reveal thickenings on the veins (harbingers of nodules). Already at this stage, bleeding is possible, which in the absence of immediate medical attention often leads to death.

- The third and fourth degrees of varicose veins of the esophagus are characterized by severe symptoms - the patient is often bothered by heartburn, pain occurs in the sternum, shortness of breath is possible, not only during physical activity, but also at rest. Often the disease is diagnosed only in the later stages of its development, when the first bleeding appears; blood is released directly from the esophagus or found in the vomit.

Endoscopic diagnosis, treatment and prevention of portal bleeding

Bleeding from varicose veins (VVV) of the esophagus is the final link in the sequence of complications of liver cirrhosis. Mortality during the first episode of gastrointestinal bleeding reaches 50%. Today, of all available diagnostic methods, esophagogastroduodenoscopy is recognized as the gold standard both in identifying varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach, and in choosing treatment tactics. The main sources of bleeding from the upper parts of the digestive tract are esophageal varices, mainly in its distal parts. Treatment of variceal bleeding includes three main areas: treatment of active bleeding (current bleeding), prevention of recurrent bleeding and prevention of first bleeding. Endoscopic treatment is considered part of a comprehensive medical and surgical treatment and is aimed at stopping bleeding or eradicating varicose veins as a potential source of bleeding. Temporary methods of hemostasis are aimed at stopping high-intensity bleeding to stabilize the patient's condition and then use one of the methods of final hemostasis. Permanent endoscopic hemostasis for bleeding from the esophagus and stomach can be achieved using several technologies - ligation, sclerotherapy, and the introduction of adhesive compositions. The most popular is endoscopic ligation. The article discusses endoscopic methods of treatment and prevention of bleeding from esophageal varices in accordance with national clinical guidelines.

Drawing. Endoscopic picture before (A) and after (B) ligation

Introduction

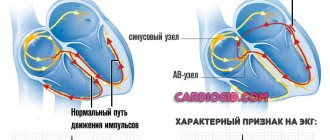

According to world statistics from developed countries, 90% of cases of portal hypertension develop against the background of liver cirrhosis (LC). Bleeding from varicose veins (VV) of the esophagus is the final link in the sequence of complications of cirrhosis caused by progressive fibrosis of the liver tissue, blockage of blood flow through its tissue, development of portal hypertension syndrome, followed by the discharge of blood along the collateral circulation, including progressive enlargement veins of the esophagus with their subsequent rupture. Today, the efforts of doctors are aimed at preventing the development of successive stages of portal hypertension and searching for therapeutic and surgical methods that can radically reduce the pressure in the portal vein system and thereby prevent the risk of bleeding from the esophagus. Another approach to preventing gastroesophageal bleeding of portal origin is the use of local endoscopic therapy aimed at eradicating varicose veins in order to prevent their rupture [1–4].

The threat of esophagogastric bleeding is considered the main, but, as a rule, delayed indication for surgical treatment of portal hypertension syndrome in 25–35% of patients with cirrhosis. Mortality during the first episode of gastrointestinal bleeding reaches 50%. In 60% of patients who have had bleeding from varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach in the past, a relapse occurs within the first year, as a result of which another 30 to 70% of patients die. Thus, it is gastroesophageal bleeding that makes portal hypertension a surgical problem in patients with cirrhosis. Unsatisfactory results of surgical treatment of patients with risk of portal bleeding served as an impetus for the development of minimally invasive endoscopic techniques [3].

Endoscopic diagnosis of varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach

Currently, of all available diagnostic methods, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the gold standard both in identifying varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach, and in choosing therapeutic tactics. Endoscopic examination makes it possible to determine not only the presence, but also the localization of varicose veins, assess the degree of their expansion, the condition of the vein wall, the mucous membrane of the esophagus and stomach, identify concomitant pathology, as well as the stigmata of the threat of bleeding [2].

Regardless of the severity of varicose veins, endoscopic examination should be carried out very carefully, taking into account that the examination itself can provoke manifestations of bleeding. In this case, you should pay attention to the adequacy of local anesthesia, avoid forced insertion of the device and rapid insufflation of air into the lumen of the stomach, preventing regurgitation of air and excessive vomiting. When starting the study, you need to make sure that you are ready to perform endoscopic hemostasis in case of bleeding. The use of ultrathin devices and transnasal examination is considered a priority.

To assess the severity of esophageal varices, two equivalent classifications are used. An earlier classification by KJ Paquet (1983) included four degrees of the disease:

- 1st degree: single venous ectasia (verified endoscopically, but not determined radiographically);

- 2nd degree: single well-demarcated vein trunks, mainly in the lower third of the esophagus, which are clearly visible during air insufflation. The lumen of the esophagus is not narrowed, the mucous membrane of the esophagus above the dilated veins is not thinned;

- 3rd degree: the lumen of the esophagus is narrowed due to bulging of the esophagus in the lower and middle thirds of the esophagus, which partially collapse with air insufflation. Single red markers or angioectasia are detected at the apices of the varicose veins;

- 4th degree: in the lumen of the esophagus there are multiple varicose nodes that do not collapse with strong air insufflation. The mucous membrane over the veins is thinned. At the tops of the varixes, multiple erosions and/or angioectasia (supervarixes) are detected.

In 1997, N. Soehendra and K. Binmoeller proposed a classification of varicose veins separately for the esophagus and stomach.

Varicose veins of the esophagus:

- 1st degree: the diameter of the veins does not exceed 5 mm, elongated, located only in the lower third of the esophagus;

- 2nd degree: the diameter of the veins is from 5 to 10 mm, tortuous, located in the middle third of the esophagus;

- 3rd degree: diameter more than 10 mm, tense, with a thin wall, located close to each other, “red markers” on the surface of the veins.

Varicose veins of the stomach:

- 1st degree: the diameter of the veins does not exceed 5 mm, poorly visible above the gastric mucosa;

- 2nd degree: diameter from 5 to 10 mm, single, polypoidal appearance;

- 3rd degree: diameter more than 10 mm, in the form of extensive conglomerates of polypoid-type nodes with thinning of the mucous membrane.

In gastric varices, there are two main types of lesions depending on the location of the veins and the extent of the lesion involving the esophagus. Combined lesions of the esophagus and stomach (Gastroesophageal Varices - GOV):

- type I – gastroesophageal varices with extension to the cardiac and subcardial parts of the lesser curvature of the stomach (GOV 1);

- type II – gastroesophageal ERVs from the esophagocardial junction along the greater curvature towards the fundus of the stomach (GOV 2).

Isolated Gastric Varices (IGV) are divided into isolated lesions of the fundus of the stomach (IGV 1) and a form with predominant lesions of the antrum (IGV 2) [1].

The main sources of bleeding from the upper parts of the digestive tract are esophageal varices, mainly in its distal parts. Gastric varices are less common and are usually less well diagnosed due to the structural features of the mucous membrane and the difficulty of examining the cardia in a retroflexed position, especially against the background of ongoing bleeding. Dilation of the venules and capillaries of the mucous membrane and submucosal layer of the stomach leads to portal hypertensive gastropathy, which, on endoscopic examination, is characterized by the presence of foci of red spots on the mucous membrane, hyperemia, mosaic pattern of the mucous membrane, and in more severe cases, diffuse dark red spots or intramucosal hemorrhages. It is believed that up to 25% of bleeding may be due to gastropathy.

Comprehensive treatment strategy for patients with portal bleeding secondary to liver cirrhosis

Treatment of variceal bleeding includes three main areas:

- treatment of active bleeding (current bleeding);

- prevention of recurrent bleeding;

- prevention of first bleeding.

Of course, endoscopic treatment is only part of a complex therapeutic and surgical treatment and is aimed at stopping bleeding or eradicating varicose veins as a potential source of bleeding.

When choosing treatment tactics in patients with cirrhosis, it is necessary to assess its functional state. For this purpose, the Child–Pugh classification is used.

In liver cirrhosis of functional classes A and B, surgical intervention aimed at reducing portal hypertension is considered possible. In case of decompensated cirrhosis (class C), the risk of surgery is extremely high, and if bleeding occurs from the esophagus and stomach, priority should be given to conservative or minimally invasive treatment methods.

The main causes of esophagogastric bleeding in portal hypertension are:

- hypertensive crisis in the portal system (increased portosystemic gradient > 12 mm Hg);

- trophic changes in the mucous membrane of the esophagus and stomach due to impaired hemocirculation and exposure to the acid-peptic factor;

- disorders of the coagulation system.

There is currently no consensus on which of these factors is the main one [1, 5–7].

The main goals of treatment are to stop bleeding, compensate for blood loss, treat coagulopathy, prevent recurrent bleeding, deterioration of liver function and complications caused by bleeding (infections, hepatic encephalopathy, etc.) [1, 5–7].

Please note that the standards have undergone changes over the past few years. A number of provisions have been confirmed from the position of evidence-based medicine. In the presence of bleeding, the primary goals of treatment are to stop the bleeding and stabilize hemodynamics by replenishing the circulating blood volume using fresh frozen plasma.

Providing assistance for acute bleeding from the esophagus in patients with cirrhosis should begin with the use of vasoactive drugs. Terlipressin (Remestip, Ferring) is considered the drug of choice. In case of acute bleeding, intravenous jet administration of the drug at a dose of 1.0 mg (10 ml) is recommended at intervals of 4-6 hours until the bleeding stops. Administration of the drug continues for the next 3–5 days with its discontinuation provided there is no bleeding within 24–48 hours. An important point: the method of administration of terlipressin allows its use at the stage of pre-hospital medical care [8].

Currently, a sufficient evidence base has been accumulated for the use of terlipressin for acute bleeding from the esophageal varices in a patient with cirrhosis. Five minutes after intravenous jet administration of 2 mg of terlipressin, the venous pressure gradient in the liver and blood flow in the portal vein significantly (30%) decreased.

In addition, placebo-controlled studies have shown that the use of terlipressin can stop bleeding from the esophagus within 12 hours in 70% of patients with cirrhosis. The survival rate one month after acute bleeding from the esophageal varices is significantly higher compared to the placebo group – 90 and 62%, respectively [9].

Please note: along with the prescription of vasoactive drugs, it is recommended to carry out antibacterial therapy from the first days to prevent portal-systemic encephalopathy. When blood hemoglobin levels decrease

As part of the therapy, an endoscopic examination is performed immediately upon admission to the hospital, the purpose of which is to establish the source of bleeding and endoscopic hemostasis. If endoscopic hemostasis is ineffective or there is massive bleeding, balloon tamponade is indicated as a temporary method of hemostasis. If complex therapy and endoscopic hemostasis are ineffective, or early recurrent bleeding, the issue of applying a transjugular portosystemic shunt or surgical intervention is considered.

Endoscopic treatment and prevention of portal bleeding

Hemostasis methods used to stop portal bleeding can be divided into temporary and permanent. Temporary ones are aimed at stopping high-intensity bleeding to stabilize the patient’s condition and then use one of the methods of final hemostasis. Temporary hemostasis is achieved by installing a Sengstaken-Blackmore obturator probe or a Danish stent.

After a diagnosis of “bleeding from the esophagus or stomach” has been made and the endoscope has been removed, a Sengstaken-Blackmore obturator probe is immediately inserted and the cuffs are inflated, thereby achieving reliable hemostasis.

Patients find it difficult to tolerate the procedure of inserting a probe into the nasopharynx (as well as keeping it in the nasopharynx for several hours), so premedication (1.0 ml of a 2% solution of promedol) is required before its introduction.

An obturator probe is inserted through the nasal passage, inserting the gastric balloon deep into the stomach. Preliminary measurement of the distance from the earlobe to the xiphoid process allows you to correctly position the obturator probe in the esophagus and stomach. Then, using a graduated syringe attached to the catheter of the gastric balloon, 150 cm3 of air (but not water!) is injected into the latter and the catheter is closed with a clamp. The probe is pulled until elastic resistance is felt, which provides compression of the veins in the cardia area. After this, the probe is fixed to the upper lip with a sticky patch.

The esophageal balloon is rarely inflated, only if regurgitation of blood continues. Otherwise, inflating the gastric balloon alone is sufficient. Air is introduced into the esophageal balloon in small portions, initially 60 cm3, subsequently 10–15 cm3 at intervals of 3–5 minutes. Compliance with these conditions is necessary in order to enable the mediastinal organs to adapt to their displacement by an inflated balloon. The total amount of injected air in the esophageal balloon is usually adjusted to 80–100 cm3, depending on the severity of esophageal dilatation and the patient’s tolerance of the pressure of the balloon on the mediastinum.

After inserting the tube, the gastric contents are aspirated and the stomach is washed with cold water. Bleeding is controlled by dynamic monitoring of the gastric contents flowing through the tube after thorough gastric lavage. To avoid bedsores on the mucous membrane of the esophagus, after four hours the esophageal balloon is deflated and, if at this moment no blood appears in the gastric contents, the esophageal cuff is left deflated. The gastric cuff is released later - after 1.5–2 hours. In patients with satisfactory liver function, the tube should be in the stomach for another 12 hours to monitor gastric contents. After removal of the obturator probe, it is necessary to immediately consider performing one of the options for permanent endoscopic hemostasis. In case of recurrent bleeding, the obturator probe should be reinserted, the balloons should be inflated, and the patient with cirrhosis (classes A and B) should be offered surgery or endoscopic hemostasis, since the possibilities of conservative therapy are considered exhausted [1].

If temporary hemostasis using a Sengstaken-Blackmore probe is ineffective, installation of a Danish stent can be used as an alternative technology. This is a plastic self-expanding covered stent, the implantation of which does not require endoscopic or radiological control. The degree of compression of the deployed stent allows achieving reliable hemostasis in a period of two to 14 days. Oral nutrition can be provided immediately after stent placement. Subsequently, the stent is removed and the issue of further treatment and the need for final hemostasis is decided.

Permanent endoscopic hemostasis for bleeding from the esophagus and stomach can be achieved using several technologies - ligation, sclerotherapy, and the introduction of adhesive compositions. In addition to achieving final hemostasis, indications for interventions of this kind are the prevention of the first episode of bleeding (primary prevention) and the prevention of recurrent bleeding (secondary prevention) from the esophageal varices in patients with portal hypertension when surgical treatment is not possible.

To ligate varicose veins, a special device is used - a ligator. The ligator consists of several parts: a distal cap with ligatures, a screw-handle, with the help of which the ligating rings are released, and a metal or nylon string connecting them, which is passed through the instrumental channel. The distal cap is made of rigid transparent plastic and fits over the distal end of the endoscope. On the outer surface of the cap there are stretched latex ligature rings. The process of releasing (dropping) the ligature ring is carried out by pulling the thread attached to it. The device is assembled into a single structure immediately before use. In our work, we often use the Speedband Superview Super7TM ligating system. This choice is due to the maximum convenience and safety of this system due to its design features. With this ligation system, the tension thread is located in a special channel of the cap, which prevents it from entering the field of view and triggering the automatic light correction of the endoscope. This in turn significantly improves visualization, and therefore the safety of the procedure itself.

The operation is performed under intravenous anesthesia. The calm state of the patient allows us to minimize technical difficulties at the stage of inserting the distal end of the device with a ligating device into the lumen of the esophagus, and is also an important point in the prevention of bleeding and rupture of the varix during ligation.

Passing the device into the esophagus may be accompanied by certain difficulties. The cap with ligatures at the distal end of the endoscope is rigid and meets natural resistance at the level of the pyriform sinus and the lower pharyngeal sphincter. The device is passed to the area of the esophagogastric junction with minimal air insufflation to avoid regurgitation and rupture of varix. A detailed examination of the stomach for diagnostic purposes, especially in the inversion position, is impractical. The distal cap with pre-installed rings significantly narrows the field of view and its illumination. By the time the decision on ligation is made, diagnostic issues must be completely resolved. If a control diagnostic study is necessary, it is better to conduct it immediately before ligation.

After holding the endoscope with the ligating device, ligation begins, starting from the area of the esophagocardial junction, just above the dentate line.

The rings are applied in a spiral. It is necessary to avoid applying ligature rings in the same plane around the circumference to prevent dysphagia in the immediate and long-term periods.

The selected varicose node is aspirated as much as possible into the lumen of the ligating cap. After this, the ligature is dropped onto the base of the node. Then it becomes clear that the ligated node changes color to bluish. It is necessary to resume the air supply and slightly remove the endoscope: these manipulations allow you to remove the ligated node from the cylinder. Depending on the severity of varicose veins, up to ten ligatures are applied per session (see figure).

Ligation of varicose veins during ongoing or ongoing bleeding has some technical features. The first ligature must be applied to the source of bleeding. Then the remaining ERVs are ligated.

On the first day after ligation, only drinking cold water is prescribed, from the second day - a certain diet (table No. 1). Large sips should be avoided. Food should be cool, liquid or pureed. For pain, it is advisable to prescribe Almagel A with a local anesthetic. For intense chest pain, the use of analgesics from the group of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is recommended. The pain syndrome usually stops by the third day.

From the second to the seventh day after ligation, the nodes become necrotic, decrease in size, and are densely covered with fibrin, followed by rejection of necrotic tissue along with ligatures and the formation of superficial ulcerations. Ulcers heal by 14–21 days, leaving star-shaped scars without stenosis of the lumen of the esophagus. By the end of the second month after ligation, the submucosal layer is replaced by scar tissue, and the muscular layer remains intact.

In the absence of complications, control EGD is performed one month after surgery. Additional ligation sessions are prescribed if the first session is insufficient, as well as if new trunks of varicose veins appear over time.

Endoscopic sclerosis of the esophageal varices is based on obliteration of varicose veins after the introduction of a sclerosant into the lumen of the vein through an endoscope using a long needle. Along with the intravasal method of sclerotherapy, there is a method of paravasal administration of sclerosant, which results in compression of varicose nodes - initially due to edema, and then due to the formation of connective tissue.

For intravasal administration, sodium tetradecyl sulfate (Thrombovar) 5–10 ml per injection is most often used. A 3% solution of Ethoxysclerol is also used. After administering the sclerosant, it is necessary to compress the vein at the puncture sites. This will ensure the formation of a blood clot as a result of swelling of the endothelium of the vessel. In one session, no more than two varicose vein trunks are thrombosed in order to avoid increased stagnation in the varicose veins of the stomach. For paravasal administration of sclerosing agents, Ethoxysklerol is usually used, which contains 5–20 mg of polidocanol in 1 ml of ethyl alcohol. Ethoxysclerol 0.5% is most often used. With each injection, no more than 3-4 ml of sclerosant is administered. Typically 15 to 20 injections are performed. In one session, up to 24–36 ml of sclerosant is consumed. The sclerosant injected through the injector creates dense swelling on both sides of the varicose vein, compressing the vessel.

The procedure is performed under intravenous anesthesia. Sclerotherapy begins from the area of the esophagocardial junction and continues in the proximal direction.

At the end of the sclerotherapy session, varicose veins are practically not visible in the edematous mucous membrane. Leakage of blood from puncture sites is usually minor and does not require additional measures.

The immediate period after a sclerotherapy session is usually not accompanied by pain. The patient is allowed to drink and take liquid food 6–8 hours after the procedure.

After the first sclerotherapy session, the procedure is repeated five days later. At the same time, they try to cover areas of the esophagus with varicose veins that were outside the coverage area of the first sclerotherapy session. The third sclerotherapy session is carried out after 30 days. At the same time, the effectiveness of the treatment, the dynamics of reducing the degree of varicose veins and the absence of the threat of bleeding are assessed. The fourth session of sclerotherapy is prescribed after three months.

A deep scar process in the submucosal layer of the esophagus and stomach during repeated sclerotherapy sessions prevents the possibility of the development of pre-existing venous collaterals and varicose transformation. Treatment continues until eradication or a positive result is achieved. This requires an average of four to five sclerotherapy sessions per year. Dynamic control is subsequently carried out once every six months. If necessary, treatment is repeated.

Currently, after the introduction of the varicose vein ligation technique into clinical practice, multi-stage sclerotherapy, which is accompanied by a large number of complications, is not a first-line method of endoscopic hemostasis and bleeding prevention and is used in combination with ligation as a tool to achieve radical intervention

In cases where sclerotherapy does not stop bleeding (with gastric varicose veins), cyanoacrylate adhesive compositions are used. Two fabric adhesives are used: N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (histoacrylate) and isobutyl-2-cyanoacrylate (bucrylate). When it enters the blood, cyanoacrylate quickly polymerizes (20 seconds), causing obliteration of the vessel, thereby achieving hemostasis. A few weeks after the injection, the adhesive plug is rejected into the lumen of the stomach.

The injection time is limited to 20 seconds due to the polymerization of histoacryl. Failure to comply with this condition leads to premature hardening of the glue in the injector, which does not allow this method to be widely used in the treatment and prevention of bleeding from varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach.

Conclusion

Solving the clinical problem of bleeding from the esophageal esophagus requires coordinated actions of specialists from various specialties: hepatologists, endoscopists, surgeons, and the constant improvement of the professional knowledge and practical skills of doctors will save the lives of our patients.

Treatment

Treatment of varicose veins of the esophagus begins with finding out the true causes of the development of the disease. If a pathology of the liver, thyroid or pancreas is diagnosed, then it must be treated - the provoking factor must be eliminated or its influence must be weakened. Medications include vitamin complexes, antacids and astringents. If bleeding is diagnosed, there is always a risk of its reoccurrence. In this case, the following is prescribed:

- blood transfusion;

- hemostatic drugs;

- introduction of a special probe that can compress the vessels.

Varicose veins of the esophagus, bleeding in which occurs too often, require surgical treatment.

Surgery is also performed if there is no effect from therapeutic treatment. Can esophageal varicose veins be stopped in this case? The prognosis is more favorable - the survival rate of patients increases 3 times. After any treatment, you must follow the dietary recommendations of doctors, undergo regular examinations and avoid excessive physical activity.

You can find out more about what esophageal varicose veins are and which doctor you should contact on the pages of our website Dobrobut.com.

2.What are the symptoms of bleeding from varicose veins?

As we have already said, varicose veins of the esophagus themselves do not cause any discomfort. But if a vein ruptures and starts bleeding, it is dangerous and requires emergency medical attention. Symptoms of varicose veins of the esophagus or stomach and the onset of bleeding from them may include:

- Vomiting blood;

- Black or bloody stools;

- Low blood pressure;

- Increased heart rate;

- Shock (in particularly serious cases).

Visit our Gastroenterology page

Diagnostics

A basic examination to confirm the diagnosis of varicose veins of the lower extremities and clarify the degree and nature of the disorders includes (5, English):

- Clinical examination. The phlebologist determines the course and condition of visible superficial veins, changes in the skin and soft tissues, and the presence of edema. Functional tests are performed to assess vertical reflux and identify the approximate level of horizontal reflux. The patient survey is aimed at clarifying the predisposing and provoking factors, duration and features of the development of the disease.

- Ultrasonography. In case of varicose veins, the most informative is not a conventional ultrasound, but an assessment of blood flow using Doppler Doppler Ultrasound (USD). The study shows the speed of blood movement, the presence of pathological veno-venous reflux, and impaired vascular patency. This information is necessary for the doctor to select the necessary treatment regimen.

- Hemostasiogram (blood tests for a comprehensive assessment of the coagulation system).

Preparation for miniphlebectomy.

Applying markings to the perforators of the lower leg, performing an ultrasound examination of the veins. According to indications, multislice computed tomography (MS CT) is performed - a high-tech study in some cases becomes the main technique for determining the picture of damage to the venous system.

In modern medicine, other diagnostic techniques are also used - plethysmography, laser Doppler flowmetry. They are not available to a wide range of patients; the results obtained are usually not critical in determining treatment tactics. Usually a basic examination is sufficient, which, if necessary, is supplemented by consultations with specialized specialists (endocrinologist, hematologist, cardiologist and others). Previously, several stages of varicose veins of the legs were distinguished. Currently, when making a diagnosis, phlebologists use the CEAP classification of chronic venous diseases, which includes characteristics of the case according to clinical, etiological, anatomical and pathophysiological characteristics.

ASSESSMENT OF PORTAL HYPERTENSION

The shortest, albeit indirect, method of assessing portal pressure involves wedged hepatic venous pressure (WHVP), which is determined by inserting a balloon catheter (from the jugular, brachial or stegnosus access) under the fluid. oroscopic guidance of the hepatic vein and “jamming” it in the small hilt (introduced all the way) or (which is still sticky) - by inflating the balloon and occluding the larger hilt of the liver vein. The correction of WHVP will ultimately involve the improvement of the internal hepatic vein pressure (for example, with ascites) by releasing the pressure in the hepatic vein - VTPV (free hepatic vein pressure - FHVP) or the internal hepatic vein pressure pressure in the empty vein, which is respected by the internal zero level. They survive when the balloon is deflated. The hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is determined by the pressure gradient in the hepatic vein. The indicator, as a matter of course, dies three times; If the values are technically correct, they are also well-designed and reliable. Although there is a gradient of pressure between the sinusoids (and not the portal vein veins) and the hepatic vein, HPVT will be advanced in case of intrahepatic causes of portal hypertension, such as cirrhosis, however normal for prehepatic causes, such as portal vein thrombosis. Normal HPVT readings are 3–5 mmHg. Art. It was found that WHVP closely correlates with portal pressure in both alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis. HPVT and changes in its symptoms, which are observed over time, may have a transferable value to the development of varicose veins in the vein, the risk of varicose bleeding, the development of non-varicose folds of portal hypertension And death. Single extinction is useful for the prognosis of both compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, while repeated extinction is useful for monitoring the effectiveness of drug therapy and the reversal of liver disease. The main considerations for the widespread viability of HPVT include the lack of evidence from practicing physicians and their continued recommendations on how to eliminate reliable and effective indicators, as well as other the simplicity of the procedure.

Duplex Doppler ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is a safe, inexpensive and effective method for screening for PG. The knobby structure of the liver, splenomegaly and the presence of colateral circulation give rise to suspicion of liver cirrhosis and PG. The diameter of the splanchnic vessels, directly and the fluidity of the bloodstream, changes in the diameter of the vessels during breathing, the index of portal venous stagnation, the pulsativity index and the resistance index of the liver, upper pars and glands also depend. Hepatic artery and hepatic vessel index. Normally, the diameter of the portal vein does not exceed 13 mm during quiet breathing, but during deep breathing it can increase by 50%. Expand a vein with a diameter of >15 mm while breathing calmly. When the pressure of the hemorrhage at the portal vein is increased and becomes monotonous (without breathing sounds) and resolves completely in the portal vein, straightened at the non-functioning portocaval shunts.

However, the creation of many ultrasonic parameters, their accuracy is insufficient, lies both in the tracking technology and in the form of additional rhythms, the development of the sympathetic nervous system, medicine, etc. So, for example, the diameter of the portal vein may increase in case of severe congestive heart failure (water from the inferior empty vein). Therefore, duplex Doppler ultrasonography itself is not recommended for establishing an accurate diagnosis of PG; it is unclear that its diagnostic value for the early stages of PG is lost (in most of these studies, patients were monitored with severe cirrosis and severe PG). Nevertheless, this method is valuable for primary closure, and also helps to identify the etiology of PG, for example, obstruction of blood vessels at different levels, highly sensitive to the identification of functional portocaval anastomoses. After placement of TIPS or portocaval anastomoses, Doppler ultrasonography is of great importance in monitoring shunt patency.

Computed tomography is a test with clear (not sharp) values, whereas ultrasonography did not give clear results. Apart from ultrasonography, CT results do not indicate the presence of gas in the intestine. Reconstruction of the vascular tree with the help of 3-D technology makes it possible to accurately create the actual portal venous system and collaterals. A common finding in portal hypertension during CT scanning is dilatation of the inferior vein. However, CT does not allow assessing the flow of blood through the venous and arterial vessels. MAR makes it possible, in addition to clear information, to obtain detailed information, for example, to assess venous flow in the portal and azygos veins. However, this does not exclude the need for invasive surveillance.

In cases of doubt about the genesis of liver disease, puncture biopsy may be necessary: necrosis of the third zone, for example, indicates portal hypertension, secondary to cardiac failure, and normal liver parenchyma - about subhepatic cause of PG.

Contraindications for liver biopsy include coagulopathy and ascites. Table 1. Causes of portal hypertension and pressure gradient in the hepatic vein

| GTPV | |||

| Rhubarb occlusion | Normal | Normal or movement | Advances |

| Subhepatic syndromes of PG | Portal vein thrombosis Thrombosis of the splenic vein Splanchnic arteriovenous fistula | ||

| Intrinsic hepatic syndromes of PG More important than the level of presinusoidal level | Schistosomiasis, primary biliary cirrosis, idiopathic PG (early stage)* Vuzlova regenerative hyperplasia* | Myeloproliferative diseases*† Polycystic disease*† Liver metastases*† Granulomatous disease † (sarcoidosis, tuberculosis)*† | |

| More important is the level on the sinusoidal or postsinusoidal level | Budd-Chiari syndrome‡ | Cirrosis of the liver Schistosomiasis, primary biliary cirrosis, idiopathic PG (late stage) Hospital and fulminant hepatitis Gostria alcoholic hepatitis Wilson's illness Veno-occlusive disease Budd-Chiari syndrome‡ | |

| Post-hepatic syndromes of PG | Obstruction of the inferior venous vein Right heart failure Clutching pericarditis Tristucular valve insufficiency | ||

* Rare causes of PG. † For the mind of the sinusoids. ‡ Sinusoidal symptoms are weak.