What happens in the body of a woman with thrombophilia?

The reason for thrombophilia is that during pregnancy a third circle of blood circulation is formed - the placental one.

The system that connects mother and fetus does not have its own capillaries, which is why blood flows directly into the vessels of the umbilical cord and placenta. Due to this, the child receives oxygen and nutrients as quickly as possible. But if a woman has problems with blood circulation, then such direct blood flow will strengthen them.

Pregnant women have increased blood clotting. This is necessary so that the expectant mother does not bleed during childbirth. But with thrombophilia, the blood already clots too quickly. A further increase in coagulability leads to the formation of blood clots, especially after 10 weeks. They clog the vessels between the maternal organ and the placenta, and between the fetus and the placenta. As a result, the child does not receive the required amount of nutrients and, most importantly, oxygen.

The consequences may be as follows:

- Miscarriage, stillbirth, fading pregnancy. Such situations are caused by oxygen starvation of the fetus (hypoxia).

- Developmental defects in a child. More often than others, problems arise with the cardiovascular and nervous system.

- Severe toxicosis. The expectant mother suffers from edema, high blood pressure, and in severe cases from eclampsia - severe convulsions that resemble epileptic seizures. To save a woman’s life, doctors have to resort to surgical delivery.

- Detachment of the altered placenta. Placental abruption is often accompanied by severe bleeding, which threatens the life of the expectant mother.

Thrombophilia is not limited only to blockage of placental vessels. Since the coagulability of all blood increases, blood clots can form in any vessels. Pregnant women often develop blood clots in the veins and arteries of the legs. The fact is that the uterus, which has increased in size, puts a lot of pressure on the veins in the groin, and due to the outflow of blood from the placenta, the vessels experience increased stress. This leads to stagnation of blood, deformation of the walls of the veins and, as a result, the formation of blood clots. Unfortunately, during pregnancy, the likelihood of developing blood clots increases by a record 200%. Women diagnosed with varicose veins are primarily at risk.

However, there is another danger - the formation of blood clots in the brain and pulmonary artery. This type of thrombosis is especially dangerous as it can lead to death.

Thrombosis in a pregnant woman: clinical manifestations

Thrombosis in pregnant women occurs with the following symptoms:

- Swelling of the affected leg;

- Redness and swelling of the skin around the affected veins;

- Local and general increase in temperature;

- Painful symptoms;

- Numbness of the affected leg;

- Fast fatiguability;

- Visibility of the vascular pattern of the affected limb.

The above is especially evident in the second half of pregnancy, when the uterus greatly increases in size. However, if there is deep vein thrombosis, symptoms appear even later.

Types of thrombophilias

The types of disease are presented in the table.

| Type of disease | Causes |

| Acquired | Concomitant diseases - polycythemia, heart disease, taking hormonal drugs, past infections |

| Gennaya | Hereditary pathologies and mutations affecting blood clotting. It occurs at the gene level and is expressed by a congenital increase in blood clotting factors. Often found in close relatives |

| Immune | Autoimmune disorders, in which the mother’s body produces antibodies to her own tissues, and alloimmune, manifested by the production of antibodies to fetal tissues |

| Vascular | Atherosclerosis, vasculitis, varicose veins, diabetic vascular lesions |

| Hemodynamic | Disruption of blood flow through vessels caused by decreased blood pressure and increased blood viscosity |

| Hematogenous | Acquired disorders of the hematocoagulant, anticoagulant and fibrinolytic systems |

The disease can develop in severe form. Most often this happens due to congenital pathologies (for example, a tendency to form blood clots).

Another risk factor is age: in women over 35 years of age who are giving birth for the first time or already have many children, thrombophilia, regardless of the type, develops more severely. Provoking factors can be abortions, severe chronic diseases, and recurrent miscarriages.

Diagnosis of thromboembolism during pregnancy

The complexity of the disease is that it is not easy to diagnose. If a woman has at least one of the symptoms listed below, she should definitely consult a doctor.

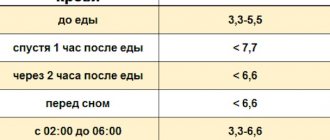

If the doctor suspects thrombophilia, he prescribes a blood test (general) and a coagulogram (clotting test) for the expectant mother. If a woman develops thrombophilia, this will affect the following indicators:

— I trimester – 750 ng/ml.

— II trimester – 1000 ng/ml.

— III trimester – 1500 ng/ml.

If there is a possibility that thrombophilia was inherited by a woman, an additional gene analysis is performed. It allows you to identify gene mutations that cause blood clots.

If the doctor suspects the immune nature of the disease, he will prescribe an analysis for antibodies to cardiolipins IgG and IgM, for antinuclear factor, and lupus coagulant. If the fears are confirmed, then we can talk about antiphospholipid syndrome. This is an immune abnormality that provokes the formation of blood clots in the placenta, which leads to impaired development of the child.

Pulmonary embolism in obstetric practice

Thromboembolic complications are an urgent problem in modern obstetrics and gynecology, since they occupy a leading place in the structure of maternal mortality and lead to severe long-term consequences. The article discusses the etiology, pathogenesis, classification, clinical picture and modern approaches to the prevention and treatment of pulmonary embolism in obstetric patients.

Key words:

pulmonary embolism, thrombophilia, thrombophlebitis, pregnancy, thrombolytic therapy.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a blockage (occlusion) of the arterial bed of the lungs (trunk, right or left pulmonary artery and/or their branches) with thrombotic masses of various calibers formed in the veins of the systemic circulation (deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the legs and ileo - caval segment, pelvis, i.e. in the basin of the inferior vena cava, rarely - in the basin of the superior vena cava), less often - in the right atrium or in the right ventricle of the heart. [10]. As a result, spasm of the branches of the pulmonary artery, acute cor pulmonale, decreased cardiac output, decreased blood oxygenation and bronchospasm develop [6,7]. However, in 50% of cases the cause of thromboembolic complications remains unknown; such thromboses are called idiopathic [3,8]. Thromboembolic complications are characterized by severe course and high mortality [3,8]. In developing countries, mortality due to pulmonary embolism ranks third after cardiovascular diseases and cancer [3,6,8]. There has been an increase in thromboembolic complications in various diseases, an increase in the frequency of postoperative and post-traumatic embolisms. Early diagnosis of these complications and timely initiation of anticoagulant therapy reduces mortality from this pathology by 4–6 times [1,2,5,7,8].

Thromboembolic complications are an urgent problem in modern obstetrics and gynecology, since they occupy a leading place in the structure of maternal mortality [5,8] and lead to severe long-term consequences [1,5,7,8]. Up to 85% of women who have suffered deep vein thrombosis during pregnancy subsequently suffer from at least one of the signs of postthrombophlebitis syndrome: chronic pulmonary hypertension, trophic ulcers [5,7]. Pregnancy increases the risk of thrombosis by 5–6 times, which is confirmed by the presence of all three factors of Virchow’s triad: slowing of blood flow, damage to the vessel wall, changes in the rheological properties of the blood [1,6,12,14]. Many authors point out that the process of gestation itself creates the preconditions for thromboembolic complications in the mother’s body. Pregnancy causes changes in blood flow in the veins of the femoroiliac triangle. The pressure of the pregnant uterus leads to disruption of venous outflow and an increase in venous pressure by an average of 10 mm Hg. An increase in the level of gestagens during pregnancy also contributes to the development of venous stasis [7,12,14,22]. At the end of the first trimester of pregnancy, venous stasis appears, which forms prothrombotic potential. At the end of pregnancy, hypercoagulation is observed, which contributes to thrombus formation in the veins of the pelvis and lower extremities. According to some authors, up to 20–24% of pregnant women have embologenic thrombophlebitis. [3,4,6,8,10,11,12,17]. Already by 25–29 weeks of pregnancy, the speed of venous blood flow decreases by 50%, and by 36 weeks it becomes minimal and is restored only by 6 weeks after delivery [3,4,6,12]. During natural childbirth and during caesarean section, damage to the pelvic veins is always present. Congenital and acquired thrombophilias play a significant role in the development of thrombosis [5,8]. Increase the risk of developing thromboembolic complications and TORHC group infections (T - toxoplasmosis; O - other infections; R - rubella; C - cytomegalovirus infection; H - herpes simplex virus) , and above all herpes simplex infection [10].

According to modern ideas in obstetric practice, the following risk factors are identified for pregnant and postpartum women: cesarean section, especially for urgent indications; operative delivery; lesions of the pelvic veins; childbirth before 36 weeks; blood group A(II); multiple births; age over 35 years; obesity; a history of many births; preeclampsia; Varicose veins; purulent-inflammatory diseases; sepsis; long (more than 4 days) bed rest before surgery; dehydration and increased hematocrit due to repeated vomiting of pregnant women, gastroenteritis, uncontrolled treatment with laxatives; prolonged immobilization or fixed positions of the legs in a car, airplane (more than 6 hours); central venous catheterization; use of oral contraceptives; extragenital pathology (rheumatic heart defects; heart failure; atrial fibrillation; diabetes mellitus; polycythemia; malignant neoplasms; nonspecific inflammatory bowel diseases; nephrotic syndrome; homocysteinuria); chemotherapy; hypercoagulation (factor V Leiden mutation; dysfibrinogenemia; increased level of factor VIII (antithrombin deficiency, protein C and S deficiency, impaired synthesis of tissue plasminogen activator)); congenital thrombophilias (antithrombin III deficiency; C-protein deficiency; S-protein deficiency; antiphospholipid syndrome). PE is most common in the postpartum period [3,17,20]. More than 80% of all cases occur after cesarean section on the 5th–7th day of the postoperative period. By this time, the formation of embologenic thrombosis is completed. Taking into account the expansion of the range of physical activity, it is likely that the weak connection of the thrombus with the venous wall is disrupted or its fragmentation, which leads to pulmonary embolism. [10,20]. The most common cause of pulmonary embolism is venous thrombosis in the femoriliac triangle [4,5,12,18,20]. To stratify the risk of venous thromboembolism, we recommend using the risk categories of maternal venous thromboembolism during pregnancy, after childbirth and after cesarean section (adapted from the French Thrombophilia and Pregnancy concensus conference, 2003) according to O. V. Grishchenko et al [10].

Acute thromboembolism manifests itself with clear symptoms only when there is occlusion of more than 30–50% of the pulmonary arterial bed. The clinical picture is determined by hemodynamic disturbances, respiratory failure and hypoxia. Large and/or multiple emboli lead to a sharp increase in the vascular resistance of the pulmonary bed, and the preload on the right side of the heart increases significantly. In some patients this can lead to cardiac arrest. Others in this situation may develop systemic hypotension, shock, and death from acute right ventricular failure. If the compensatory mechanisms are adequately triggered, the patient does not die immediately, but in the absence of treatment, secondary hemodynamic disorders quickly progress, especially when thromboembolism recurs in the coming hours.

Significantly worsen compensatory capabilities and worsen the prognosis of cardiovascular disease. In milder cases, hemodynamic disturbances are less pronounced and are clinically manifested by hemoptysis, pleurisy and other symptoms of pulmonary infarction [10].

Until now, we use the clinical classification of pulmonary embolism (ICD-10):

1) According to the severity of the development of the pathological process: acute; subacute; chronic (recurrent).

2) According to the volume of vascular damage: massive (accompanied by shock/hypotension); submassive (accompanied by right ventricular dysfunction without hypotension); non-massive (no hemodynamic disturbances or signs of right ventricular failure).

3) According to the presence of complications: with the development of pulmonary infarction; with the development of cor pulmonale; no mention of cor pulmonale.

4) By etiology: associated with deep venous thrombosis; amniotic, associated with: abortion, ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy and childbirth; idiopathic (without an established cause).

In the new guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (2008), the terms “massive”, “submassive”, “non-massive” are considered incorrect. It is proposed to stratify patients into high and low risk groups, and among the latter, moderate and low risk subgroups are distinguished. High risk is considered to be the risk of early death (death in hospital or within 30 days after PE) exceeding 15%, moderate - up to 15%, low - less than 1%. To determine risk, it is recommended to focus on three groups of markers: clinical, markers of right ventricular dysfunction and markers of myocardial damage. The high-risk group is characterized by: shock or hypotension for 15 minutes, unrelated to arrhythmia, hypovolemia or sepsis; signs of right ventricular dysfunction in the form of echoCG markers of its dilatation, hypokinesia or overload, dilatation of the right ventricle according to the results of spiral computed tomography (CT). High risk is also characterized by an increase in the blood level of brain natriuretic peptide and an increase in pressure in the cavities of the right heart according to the results of cardiac catheterization. Myocardial damage is characterized by a positive test for troponin T or I. In the moderate risk group, the hemodynamics are relatively stable, there are markers of right ventricular dysfunction and myocardial damage. In patients with a low risk of death against the background of stable hemodynamics, signs of right ventricular dysfunction and myocardial damage are not detected [10].

The probability of pulmonary embolism can be assessed using the MW Roges and PS Wells scale (2001) or the so-called Geneva scale (G. le Gal et al., 2006) [5].

PE is characterized by a nonspecific clinical picture and similarity to other diseases. However, in 90% of cases, the suspicion of pulmonary embolism is based on clinical symptoms. All symptoms are divided into general, functional, painful and congestive [3,8,11,13,16]. These symptoms form symptom complexes that develop with pulmonary embolism. These include: acute cardiovascular failure, acute coronary insufficiency, acute asphyxia, cerebral syndrome, abdominal syndrome, allergic syndrome. [3,8,10,11]. The most common symptoms of pulmonary embolism are inspiratory dyspnea, tachycardia (more than 100 beats/min), chest pain, hemoptysis, fever (more than 38.50C), and dry cough. Wheezing is heard in the lungs. There is excitement and a feeling of “fear of death,” sweating, pallor or cyanosis, a drop in blood pressure, and fainting [1,3,4,5,6,8,10,11,12,17,22,23].

The change in the patient's condition with pulmonary embolism occurs suddenly. He becomes restless or apathetic. With occlusion of small branches of the pulmonary artery, only general weakness may be observed, without clinical manifestations [17,20]. Patients may complain of tightness in the chest, a feeling of pressure in the heart. The development of rapidly progressing tachycardia is typical. Characterized by a sharp drop in blood pressure. The skin may take on a pale or grayish tint. With massive pulmonary embolism, cyanosis of the neck and upper half of the body suddenly appears. When small branches of the pulmonary artery are occluded, cyanosis occurs only on the lips and wings of the nose. As acute right ventricular failure develops, dyspnea or tachypnea develops. There is swelling of the neck veins and pathological pulsation in the epigastrium. A systolic murmur and a “gallop rhythm” are heard on auscultation above the xiphoid process. An accent of the second tone is heard above the pulmonary artery, however, due to physiological moderate hypertension in the pulmonary circulation, in pregnant women the significance of this symptom is leveled out. An important sign of pulmonary embolism is hemoptysis, which usually appears on days 3–7 and indicates the development of pulmonary infarction [3,8,10,11]. In the embolic zone, it is possible to develop exudative reactive pleurisy, which is manifested by acute pain in the chest, aggravated by breathing and coughing. Irritation by the embolus of the nerve endings in the wall of the pulmonary arteries causes unbearable pain. In severe hemodynamic disorders, microcirculation is disrupted, resulting in acute renal failure and cerebral disorders (hypoxemia, convulsions, vomiting, drowsiness, fainting, coma). At 2–5 weeks after PE, an allergic syndrome may develop, including the appearance of skin rash, itching and eosinophilia [3,8,11,19]. With a pulmonary infarction, jaundice may be observed, more often in patients with heart failure or due to hyperbilirubinemia caused by the decomposition of hemoglobin at the site of the infarction [3,8,10,11,19]. The onset of PE in pregnant women may be a short-term fainting or loss of consciousness, which may be underestimated as a symptom of thromboembolism. Management of pregnant women with PE or at high risk of its development is carried out according to a specific algorithm, which includes: identifying groups at risk of developing PE and carrying out its prevention, diagnosing PE when clinical symptoms appear, comprehensive treatment of patients with PE, resolving the issue of the possibility of carrying a pregnancy, management of pregnancy and delivery [6,13,18].

Research methods for pulmonary embolism are divided into 3 groups: mandatory, verifying and clarifying [6,8]. Mandatory studies (blood pressure monitoring, electrocardiogram recording, chest radiography, echocardiography, blood gas analysis, determination of D-dimers in the blood, troponin T and I, MB fraction of creatine phosphokinase) are carried out in all patients with suspected PE [8,12,18 ,20]. Verifying studies (pulmonary angiography, spiral computed tomography and ventilation-perfusion lung scintigraphy) make it possible to determine the location, nature and volume of the embolism. Clarifying studies (transesophageal echocardiography, ultrasound of the veins of the lower extremities, pelvic veins, inferior vena cava, impedance plethysmography of the veins of the lower extremities, contrast venography, phleboscintigraphy with Tc99m) identify the source of pulmonary artery embolization [3,7,8,13].

If PE is suspected in pregnant women, diagnosis should begin with determining the level of D-dimers and ECG [7]. However, the level of D-dimers in pregnant women is not a specific marker of PE, since during pregnancy it increases to 1000 μg/L [5,6,7,8,12,16,19,20]. An increase in D-dimers to 2000 µg/l or more is diagnostically significant, along with clinical manifestations of pulmonary embolism [8,20]. Electrocardiography allows you to diagnose signs of overload of the right heart and myocardial ischemia [5,7,8,9,13]. Massive thromboembolism is characterized by disturbances in metabolic processes in the right ventricle, which are manifested by tachycardia, right bundle branch block, extrasystole, atrial fibrillation and flutter. ECG signs of acute cor pulmonale in patients with pulmonary embolism are: deviation of the electrical axis to the right; identification of a pathological P-pulmonale wave (in leads III, AVF, V1, V2); nonspecific changes in the RS-T complex (in leads III, AVF, V1, V2); right bundle branch block; extrasystole, tachycardia [5,8,10,11,12,17,23]. X-ray signs of PE are not very specific and are detected only in 40% of patients and help to exclude other causes of shortness of breath and chest pain [4,5,6,7,9,16,17,19]. These include: bulging conus pulmonary; sharp expansion of the root of the lung; expansion of the heart shadow to the right; picture of “amputation of the branches of the pulmonary artery”; decreased transparency of the ischemic lung; depletion of the pulmonary pattern (Westermarck's symptom); the presence of a triangular shadow of the infarction (Hamser's sign); high and sedentary standing of the dome of the diaphragm on the affected side; pleural effusion [4,6,7,8,12,17]. EchoCG is of great importance and is used for the differential diagnosis of PE with other pathologies of the cardiovascular system [13]. PE is characterized by: hypertrophy, dilatation and hypokinesia of the right ventricle; tricuspid regurgitation; blood clots in the pulmonary bed or heart; signs of pulmonary hypertension; pericardial effusion; paradoxical movement of the interventricular septum; thickening of the anterior wall of the right ventricle and interventricular septum in the early stages of the development of pulmonary embolism. [5,6,8,13]. A study of the blood gas composition in patients with pulmonary embolism reveals hypoxia and hypocapnia, however, in 15%, the gas composition of arterial blood may remain normal [5,6,8,10,11,12,13]. When the level of D-dimers increases, compression ultrasonography of the veins of the lower extremities is used. Detection of proximal deep vein thrombosis is a sufficient criterion for prescribing anticoagulant therapy without further diagnosis [5,6,11,22]. Spiral computed tomography is used in the absence of results from previous studies. It helps to visualize thromboembolism in the pulmonary arteries down to the subsegmental level of the pulmonary arteries [5,16,17,23]. The ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy method is non-invasive and highly informative. It is based on the intravenous injection of technetium (Tc99m)-labeled particles of albumin macroaggregates and makes it possible to identify an area of the lungs with impaired blood supply - a “cold spot”. [5,6]. PE is characterized by the detection of pulmonary hypoperfusion against the background of normal ventilation (perfusion-ventilation mismatch) [5]. Angiopulmonography is one of the most informative methods for diagnosing pulmonary embolism, as it allows one to verify a defect in the filling of a vessel and its “amputation” as a result of blockage by a thrombus, which makes it possible to determine the exact localization of even small thrombi up to 1–2 mm in subsegmental arteries. However, its use is limited due to the high risk of complications and significant radiation exposure to the fetus [3,5,6,8,12,20].

For pulmonary embolism in pregnant women and after childbirth, the treatment strategy depends on the degree of risk and in some respects differs from the standard one. Treatment of confirmed thromboembolism is divided into symptomatic and specific [5,6,9]. As part of symptomatic therapy: resuscitation measures and oxygen therapy are carried out, and, if necessary, artificial ventilation (with increasing hypoxemia, paO2 < 60 mm Hg); when the level of systolic blood pressure (SBP) drops <90 mmHg. Art., intravenous administration of hydroxyethylated starch in a volume of no more than 500 ml is indicated (until the SBP reaches more than 100 mm Hg), dopamine, dobutamine are used for inotropic purposes; To relieve pain, fentanyl with droperidol and morphine are used (with the development of pulmonary edema and the ineffectiveness of other drugs); to relieve bronchospasm and arteriolospasm, 1 ml of PgE2 (prostenon, prostin) is injected intravenously; if there is no effect, repeated intravenous administration of 1 ml of PgE2 is indicated; it is also possible to use atropine at a dose of 0.5 ml of 1% solution; the prescription of fibrinolysis inhibitors is indicated (trasylol or contrical is administered intravenously at a dose of 20,000–50,000 units); To prevent the development of infarction-pneumonia, broad-spectrum antibiotics (cephalosporins, macrolides, semi-synthetic penicillins) are used [6,7,12,13,22]. The main role in the management of patients with pulmonary embolism belongs to anticoagulant therapy. Timely initiation and active anticoagulant therapy significantly reduces the risk of death and recurrent thromboembolism, and is therefore recommended not only in persons with a confirmed diagnosis, but also in cases of a sufficiently high probability of pulmonary embolism during the diagnostic process [10]. Systemic thrombolysis during pregnancy is indicated only in cases of massive pulmonary embolism. It is most effective in the first 24–72 hours. [3,6,11,13]. Thrombolysis is absolutely contraindicated in cases of internal bleeding, recent intracranial hemorrhage, and the first 15 days of the postoperative and postpartum period [11,13]. In clinical practice today, streptokinase, urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator (alteplase) are used [3,13]. Thrombolysis regimens are presented in Table 1 [4,5,6,13]..

Table 1

Systemic thrombolysis regimens depending on the drug chosen

| Medicine | Starting dose | Maintenance dose | Note |

| Streptokinase | 250,000 units are diluted with 30 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride solution and administered intravenously over 30 minutes (using a syringe dispenser, speed 2 ml per hour) | continue infusion of the drug at a rate of 100,000 units per hour for 24 hours. | Before the procedure, administer hydrocortisone 100 mg or prednisolone 90–120 mg intravenously, as well as 2 ml of a 2% solution of chloropyramine. GCS are re-administered after 12 hours. |

| Urokinase | 4400 U/kg administered intravenously over 10 minutes | infusion over 12 hours at a rate of 4400 U/kg/hour. | |

| Alteplase | administered intravenously as a bolus of 15 mg over 15 minutes. | Then 0.75 mg/kg is administered intravenously over 30 minutes, and then 0.5 mg/kg over 60 minutes. |

The effect of alteplase occurs within 15 minutes, which determines its advantage over other thrombolytics [5]. However, there is currently no reliable data on the effectiveness of thrombolysis and safety for the mother and fetus [3,11,20,21,22]. After thrombolysis, it is necessary to prescribe anticoagulant therapy to prevent rethrombosis, based on the use of unfractionated and low molecular weight heparins, as well as indirect oral anticoagulants [8,11,12,13,15,17,24]. In obstetrics, it is advisable to use unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin, since they do not penetrate the placenta and do not cause side effects on the fetus [3,4,5,6,8,12,13,15, 16,17,19,20,22, 23]. A rapid effect is achieved by administering unfractionated heparin (UFH). If there is a high probability of PE, it is permissible to begin administering heparins before obtaining the results of an objective study (100 U/kg for 5 minutes), which will prevent further growth and formation of a blood clot [1,3,5,12,13,16,18,22]. According to indications, transfusion of fresh frozen plasma at a rate of 10-15 ml/kg may be indicated simultaneously with heparin [13]. When using UFH (the goal of heparinization is to increase the aPTT by 1.5–2 times), the aPTT should be monitored after 6 hours, and subsequently, after selecting an individual dose, after 12–24 hours. After stopping the acute phase of pulmonary embolism, you should switch to titrating UFH at a dose of 30,000–50,000 units per day, then 1000–2000 units/hour. After 5–7 days of therapy, unfractionated heparin begins to be administered subcutaneously or is replaced with low molecular weight heparins [4,6,17]. Every three days it is necessary to monitor the INR, platelet count and antithrombin III [1,4,6,13]. If bleeding occurs, intravenous administration of protamine sulfate 50–100 mg is indicated, after which after 15 minutes the aPTT is monitored and a decision is made to resume heparin titration [12,13,23]. The UFH dose adjustment scheme is presented in Table 2 [13].

table 2

UFH dose adjustment scheme based on the dynamics of APTT increase

| Increase in APTT (x times) | Heparin dose adjustment |

| APTT < x 1.2 | Repeat bolus + titration |

| APTT = x 1.2–1.5 | Bolus 2000* - 2500 U + titration dose increase by 2 U/kg per hour. |

| APTT = x 1.5–2.3 | No correction required |

| APTT = x 2.4–3.0 | Reduce titration dose by 2 U/kg per hour. |

| APTT > x 3.0 | Stop titration for 1 hour, then titrate by reducing the dose by 4 U/kg per hour. |

| * - for patients weighing less than 80 kg. | |

When carrying out anticoagulant therapy, careful monitoring of hemostasis should be carried out (Table 5).

Some authors recommend prescribing calcium supplements at a dose of 1500 mg/day simultaneously with the use of heparin for the prevention of osteoporosis [8,13,20,23]. Table 2 shows the scheme for adjusting the dose of UFH according to the dynamics of the increase in aPTT. Intravenous infusion of heparins (UFH and LMWH) should be stopped 4–6 hours, and subcutaneous administration 12–24 hours before delivery [6,8,12,20,22,23].

Table 3

Basic criteria for monitoring anticoagulant therapy in pregnant women

| Anticoagulant | Criteria for monitoring hemostasiogram | |

| indicator under study | required value | |

| UFH (heparin) | APTT | 1.5–2 times higher than normal |

| LMWH (fragmin, fraxiparine, clexane) | D-dimer | Not higher than 500 µg/l |

| Not higher than 2–5 μg/ml | ||

| Indirect anticoagulants (warfarin) | INR | Should be between 2 and 3 |

| or PTV | 1.5–2 times higher than normal | |

| UFH, LMWH, indirect anticoagulants | Fibrinogen, Tr, Er, Ht numbers, antithrombin III, liver transaminases, blood proteins | Within normal physiological values |

For unplanned births, they are canceled immediately after the onset of labor [6]. Anticoagulant therapy should be carried out for 3–6 months during pregnancy and 6–12 weeks after childbirth [3,12,13,16,22], as well as for up to 12 months for women with antiphospholipid syndrome, thrombophilias and when thrombophilia is combined with recurrent venous thrombosis [6,7,22]. After childbirth, it is more advisable to use LMWH [14,20]. Their appointment is possible 3–6 hours after birth or 6–8 hours after cesarean section. To avoid the occurrence of spinal and epidural hematoma, it is not recommended to perform regional anesthesia within 24 hours after taking the last therapeutic dose of heparin and within 12 hours after the last prophylactic dose [5,14,20,22]. Due to severe side effects, the use of oral coagulants (warfarin) during pregnancy is contraindicated [3,12,15,22]. Prescription of warfarin is possible in the postpartum period from 2–3 days, in parallel with the administration of heparins, the starting dose of the drug is 5 mg per day. Once the INR increases (monitored once daily) by a factor of 2, heparins are discontinued, and warfarin therapy continues for up to 12 weeks [5,6,7,14,20].

Vava filters are used only in case of contraindications to anticoagulant therapy, its complications and recurrent pulmonary embolism with the formation of pulmonary hypertension, as well as if extensive thromboembolism occurs 2 weeks before birth [1,4,8,13,19,20,21]. Installation of vena cava filters is contraindicated in cases of septicemia and uncontrolled coagulopathy [8,13,23].

The method of choice for delivery in patients with pulmonary embolism is cesarean section, which is contraindicated if the patient is in extremely critical condition and there is no labor. If the condition of the woman and the fetus is satisfactory, vaginal delivery is possible, but provided that the episode of pulmonary embolism occurred at least 1 month ago and the patient has vena cava filters installed [13].

An important factor in preventing thromboembolic complications is their rational nonspecific prevention. Which includes the use of agents that enhance the antithrombotic properties of the vascular wall, such as phytin, glutamic acid (prescribed 2–3 weeks before birth and within 2–3 weeks after birth); use of elastic knitwear; the use of non-invasive low-frequency hemomagnetic therapy [5,7]. If a floating thrombus of the lower extremities is detected, percutaneous implantation of a vena cava filter is advisable. It is possible to use phlebotonic agents (venoruton, detralex, lyoton-gel, heparin ointment, troxevasin ointment). It is important to ensure adequate pain relief during labor [1,6,11,12].

Thromboembolic complications increase the disability of patients and worsen their quality of life. Pulmonary embolism was one of the unpreventable causes of maternal mortality. However, the achievements of modern medical science make it possible, in some cases, to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality [8,9,14,20,21,22].

Literature:

1. Venous complications in pregnant women / V. I. Medved, V. A. Benyuk, S. D. Koval / Medical aspects of women’s health No. 7–2010, p. 29–33.

2. Diagnosis and treatment of acute pulmonary embolism / National recommendations / Minsk 2010

3. Clinical lectures on obstetrics and gynecology. Volume 1. Obstetrics / ed. A. N. Strizhakova, A. I. Davydova, I. V. Ignatko.-M.: Medicine, 2010.-pp.473–495.

4. Makatsaria, A. D., Bitsadze O. V. Thrombophilias and antithrombotic therapy in obstetric practice. - M.: “Triad X” - s. 101–904.

5. National recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of acute pulmonary embolism / S. G. Sudzhaeva, Yu. P. Ostrovsky, O. A. Sudzhaeva, N. A. Kazaeva.-M.: 2010.-pp.4–12, 14–22, 39–42, 57–66.

6. Peresada, O. A. Current problems of obstetrics and gynecology - Minsk: FUA-inform, - 2009. - pp. 66–96.

7. Peresada, O. A. Women’s reproductive health: A guide for doctors. - M.: MIA, 2009. - pp. 460–508.

8. Thrombohemorrhagic complications in obstetric and gynecological practice: A guide for doctors / ed. A. D. Makatsaria.-M.:MIA,-2011.-pp.91–142.

9. Thrombotic conditions in obstetric practice / ed. Yu. E. Dobrokhotova, A. A. Shchegoleva.-M.:GEOTAR-Media,-2010.-p.69–72.

10. Thromboembolism in obstetric practice/ Grishchenko O. V., Korovay S. V./ Emergency Medicine No. 3 (34)-2011, pp. 33–43.

11. Thromboembolic complications during pregnancy and the postpartum period/ Smirnova T. A., Klimantovich A. I., Deychik D. A./ Medical journal No. 2–2012, p. 106–112.

12. Thromboembolic complications in obstetric practice / E. N. Zelenko, L. A. Smirnova, V. A. Zmachinsky, S. L. Voskresensky. - Minsk: BelMAPO, 2010. - pp. 3.-33.

13. Kharkevich, O. N., Kurlovich I. V., Korshikova R. L. “Management of pregnancy and childbirth in women with pulmonary embolism” / Medical News, 2007. - No. 2. - vol. 1. - c. 19–28.

14. Ageno, W., Squizzato A., Garcia D. et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of venous thromboembolism // Semin. Thromb. Hemost. — 2006 Oct.; 32 (7).-p. 651–8.

15. Andra, H. James. Venous Thromboembolism in pregnancy // Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology.-2009, 29.-p.326–331.

16. James Drift. Thromboembolism.Reducing maternal death and disability during pregnancy// British Medical Bulletin.-2003.-67 (1).-p.177–190

17. Johenna Weiss, Ramada S. Smith Emergency conditions in obstetrics // Obstetrics and gynecology, edited by Alan H. De Cherny, Lauren Nathan, vol. 1M.: MEDpress-inform.-2008.-pp.745–750.

18. Lee T. Dresang, Pat Fontaine, Larry Leeman, Valery J. King. Venous Thromboembolism During Pregnancy//American Family Physician.-2008.-No. 15;77(12).-p.1709–1716.

19. Maristella D'Uva, Pierpaolo DiMicco, Ida Strina, Giuseppe De Placido.Venous Thromboembolism and Pregnancy//Journal Of Blood Medicine.-2010.-No. 1.-p.9–12.

20. Martin N. Montoro. Venous Thromboembolism and Inherited Thrombophilias / Management of Common Problems in Obstetrics and Gynecology edited by T. Murphy Goodwin, Martin N. Montoro, Laila Muderspach, Richard Paulson, Subir Roy.-S.: Wiley-Blackwell, -2010.-p.117–126.

21. Paul E. Marik, Lauren A. Plante. Venous Thromboembolic Disease and Pregnancy//The New England Journal Of Medicine.-2008.-359:2025–2033.November 6, 2008.

22. Rosenberg VA, Lockwood CJ Thrombembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2007; 34.-p. 481–500.

23. Shannon M. Bates, Jan. A. Greer, Ingrid Pabinger, Shoshanna Sofaer, Jack Hirsh. Venous thromboembolism, Thrombophilia, Antithrombotic Therapy, and Pregnancy // Chest.-2008.-Vol.133.-p.844–886.

24. Tapson VF Acute Pulmonary Embolism // New England J. Med. — 2008.— Vol. 358. - p. 1037–1052.

Treatment of thrombophilia

Before therapy, two tasks are set: firstly, it is necessary to eliminate blood clots, and secondly, to remove the cause that led to their formation.

Treatment usually includes:

Also, women who are at high risk of developing blood clots are recommended to wear compression stockings; they support the veins and help maintain their elasticity. It is advisable to lie down with your legs raised and placed on soft support.

Diagnosis of thrombosis in pregnant women

Before prescribing thrombosis treatment to a patient, CELT specialists conduct a comprehensive diagnosis aimed at making an accurate diagnosis. As a rule, the latter does not cause difficulties. Our phlebologist takes a medical history and prescribes the following tests for the pregnant woman:

- Complete blood count - to assess the functioning of the coagulation system;

- Ultrasound scanning of the fetus - to determine its condition and eliminate the risk of hypoxia;

- Dopplerography - to determine the condition of blood veins and detect disturbances in blood flow.

Planning pregnancy with thrombophilia

If a woman knows that she has thrombophilia, she should see a doctor and start taking medications to alleviate her condition before conceiving. This will make pregnancy easier. You should also strictly follow all the doctor’s recommendations and do not skimp on compression garments or medications.

In particular, to improve the elasticity of blood vessels and maintain normal clotting, long-term intake of vitamins E and C, as well as rutin, is prescribed. All of them are included in the Synergin complex, which is also approved for pregnant women.

THIS IS NOT AN ADVERTISING. THE MATERIAL WAS PREPARED WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF EXPERTS.

Our doctors

Malakhov Yuri Stanislavovich

Doctor - cardiovascular surgeon, phlebologist, Honored Doctor of the Russian Federation, Doctor of Medical Sciences, doctor of the highest category

Experience 36 years

Make an appointment

Drozdov Sergey Alexandrovich

Cardiovascular surgeon, phlebologist, Doctor of Medical Sciences

47 years of experience

Make an appointment