Sodium in food: main sources in the diet

Sodium enters the body with food and, in much smaller quantities, with water. Many foods rich in sodium do not contain sodium. The main source of sodium in the diet is table salt (also known as sodium chloride or NaCl), which is added to foods during the cooking phase to enhance the flavor of meats, vegetables, or soups and sauces. It also acts as a natural preservative to protect foods from spoilage.

Sodium is also found in highly processed foods:

- fast food;

- sauces and dry soups;

- ready-made dishes (not only salty, but also sweet);

- processed meats (cold cuts, sausages, sausages, salami, wild boar, pate and canned meats).

The sodium content in 100 grams is up to half the daily value of this ingredient for an adult!

sodium in food

Sodium is also found in large quantities in the following foods:

- bread and buns;

- salty snacks: sticks, crackers, chips, vegetable juices, canned goods (for example, canned beans);

- bouillon cubes;

- universal seasoning with dried vegetables for dishes;

- pickled vegetables: olives, capers, peppers, onions, pickles (pickled cucumbers, sauerkraut, beetroot starter);

- smoked and salted fish, canned fish;

- rennet cheeses, that is, yellow ones (for example, Parmesan, Roquepol, feta, Camembert);

- some dairy products: grain cheese, Turkish drink “Ayran”.

Daily sodium requirement

The level of sodium in the blood in women and men depends on:

- age;

- gender;

- level of physical activity.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends:

- adults – consume no more than 5 grams of salt per day from all sources (1 level teaspoon)

- children – no more than 3 g (about 2/3 flat teaspoons).

5 grams of salt contains about 2.4 grams of sodium. The normal sodium content in body fluids for an adult is from 136 to 145 mmol per liter of blood.

Causes and consequences of sodium deficiency in the body - hyponatremia

Sodium requirements depend on many factors, including physical activity. Causes of sodium deficiency include:

- insufficient sodium intake (low sodium diet);

- overhydration of the body - increased excretion of sodium in urine or sweat (for example, with regular exercise, dehydration on a hot day);

- food poisoning with diarrhea and vomiting;

- use of laxatives or dehydrating substances;

- cirrhosis of the liver;

- hypothyroidism,

- kidney, heart, liver failure;

- Bartter's syndrome (also known as inappropriate vasopressin release syndrome).

Lack of sodium in the human body, that is, hyponatremia , is very dangerous, as it can lead to dehydration, disruption of the functioning of many organs, and if the level of sodium in the body is less than 110 mmol/l, even death. Fortunately, this condition is very rare.

Hyponatremia can be mild, chronic, or acute. Main symptoms of sodium deficiency:

- headache and dizziness;

- lack of appetite;

- gastric symptoms: diarrhea, constipation, vomiting;

- trembling of the muscles of the arms and legs;

- low blood pressure;

- drowsiness and weakness;

- confusion and difficulty concentrating;

- difficulty remembering;

- dry mucous membranes and skin.

normal sodium level in blood

Interference:

- ACTH, anabolic steroids, androgens, carbenicillin, carbenoxalone, clonidine, corticosteroids, diazoxide, enoxolone, estrogens, guanethidine analogues, lactulose, mycorice, methoxyflurane, methyldopa, oral contraceptives, oxyphenbutazone, phenylbutazone, reserpine, sodium bicarbonate.

- Aminoglutethimide, aminoglycosides, ammonium chloride, amphotericin B, ACE inhibitors, captopril, carbamazepine, carboplatin, chlorpropamide, cholestyramine, cisplatin, clofibrate, cyclophosphamide, desmopressin, diuretics, fluoxetine, hypertonic glucose solution, haloperidol, heparin, indomethacin, ketoc onazole, lithium, lorcainide , miconazole, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oxytocin, phenothiazines, thienylic acid, tolbutamide, tricyclic antidepressants, vasopressin, vinblastine, vincristine.

Causes and consequences of excess sodium in the body - hypernatremia

Excess sodium, or hypernatremia , is most often caused by poor diet - excessive consumption of foods containing sodium. Inadequate fluid intake, fever, and increased metabolism (common, for example, with thyroid hormone disorders) can also contribute to elevated blood sodium levels.

Too much sodium is also dangerous because it causes too much water to be retained in the cells and tissues of the body. This may lead to:

- increased blood pressure;

- narrowing of blood vessels;

- development of high blood pressure.

The consequences of excess sodium are swelling of the legs and body, water cellulite.

Chronic excess sodium can lead to:

- renal failure;

- nephrolithiasis;

- cardiovascular diseases.

This increases the risk of stroke, aneurysms and heart attack. More often than not, excess sodium causes hypertension and worsens the disease in people who have already been diagnosed (although this is not a rule because not all patients experience increased blood pressure after eating salt).

High salt intake (the most common cause of excess sodium in the body):

- increases the risk of developing stomach cancer;

- increases the excretion of calcium from the body, which negatively affects the mineralization of bones and teeth.

How to reduce your sodium intake?

European society far exceeds salt intake recommendations, resulting in elevated sodium levels in the body. To prevent hypernatremia and reduce the risk of hypertension, doctors recommend eating a low-sodium diet, called the DASH diet.

This is the healthiest diet that suits everyone. You can stick to it without worrying about your health or nutritional deficiencies. It prevents violations such as:

- arterial hypertension;

- obesity;

- atherosclerosis;

- diabetes.

Avoid over-salting foods and limit your intake of foods that are extremely rich in this element (particularly fast food and salty snacks). It is also recommended to increase your intake of foods rich in magnesium (whole grains, cocoa, nuts) and potassium (vegetables and fruits).

You can replace salt in food with many spices, such as basil, oregano or marjoram. Low amounts of sodium can be found in vegetables, fruits and unsmoked meats, so these foods should form the basis of the DASH diet.

People have long had a difficult relationship with salt. The most popular seasoning all over the world is not just that, but also vitally necessary for humans. According to L. Dahl, perhaps salt is the most important nutritional factor affecting the control of blood pressure (BP) [1]. Moreover, the consumption of table salt is such an important component of nutrition that eliminating salt from the diet can lead to an irreversible catastrophe, namely death. After all, without salt, or rather without sodium chloride (NaCl), our body simply would not be able to perform its functions normally. It is sodium, which is mainly found in salt, that will be discussed. For your information, 100 g of salt contains 38.183 mg of sodium.

The main physiological functions of sodium are as follows:

— ensures the penetration of amino acids and carbohydrates into cells;

— stimulates the activity of digestive enzymes;

- participates in the passage of impulses along the nerve fiber along with potassium;

- accumulates fluid in the body.

The most important property of sodium from a physiological point of view is its ability to bind water. Thus, 1 g of salt is able to retain up to 100 ml of water in the body. When tissues and blood vessels are oversaturated with salt, an excess of water occurs in the body, which leads to an overload of the activity of all organs involved in a particular process. For example, the heart is forced to work harder, and the kidneys are forced to remove excess amounts of both water and salt from the body.

Currently, in many countries, salt intake ranges from 9 to 15 g per day [2]. Women consume slightly less salt than men. In our country, according to data collected in Moscow, they consume an average of 12 g of salt per day [3]. However, this amount of salt, according to modern researchers, is excessively high and harmful to health, since the human body needs and only needs 2-3 g of sodium per day, and in the case of increased sweating and significant loss of water - a little more. For a healthy person, 5-7 g of table salt per day does not pose any risk. However, continually exceeding this limit has consequences. For those suffering from arterial hypertension (AH) or prone to this disease, salt can be harmful. Why did salt receive such an unattractive status?

Salt intake and hypertension

Although salt is highly regarded by many people as a versatile seasoning, its intake has long been associated with elevated blood pressure and, more recently, with other health indicators [1–3].

Mechanisms linking salt intake and increased blood pressure include increased extracellular volume and peripheral vascular resistance due in part to increased sympathetic nervous system activity.

The results of epidemiological studies show that the development of hypertension is associated with salt consumption, there is a close relationship between sodium intake and the incidence of hypertension, and in addition, limiting sodium intake contributes to a significant reduction in blood pressure [4]. The authors of a meta-analysis of several randomized trials lasting from 1 month showed that a moderate reduction in salt intake caused a significant decrease in blood pressure in both individuals with and without hypertension: a reduction in salt to 6 g per day led to a decrease in blood pressure by 7/4 mmHg. in hypertensive patients and by 4/2 mm Hg. in normotensive patients [5]. One well-controlled, double-blind, crossover study examined three levels of salt intake in 20 participants with untreated hypertension in whom salt was reduced from 11.2 to 6.4 and 2.9 g per day. Before the study, blood pressure was 163/100 mmHg, salt intake was 11.2 g/day; when salt intake was reduced to 6.4 g/day, blood pressure decreased by 8/5 mmHg. and reached 155/95 mm Hg. With a further reduction to 2.9 g/day, blood pressure decreased by 8/4 mmHg. - up to 147/91 mm Hg. 19 out of 20 participants were observed for 1 year, their blood pressure did not exceed 145/90 mm Hg. at the lowest salt intake (up to 3 g/day).

According to H. Blackburn, who devoted his population-based work to the study of hypertension: “...a decrease in blood pressure among the population by 1-3 mm Hg. will have the same effect as all antihypertensive drugs taken together that are currently prescribed to patients with hypertension” [6]. And according to S. McMahon, expressed on the basis of an analysis of the results of numerous population studies, “...a decrease in diastolic blood pressure by 2 mm Hg. reduces the risk of death from stroke by 13%, and by 6 mm Hg. - by as much as 43%" [7].

The relationship between salt intake and hypertension has changed several times. The idea of the dangers of excess salt consumption was expressed in ancient Egypt. And in 1948, W. Kempner hypothesized that excess salt can increase blood pressure and proposed a rice-fruit-sugar diet with a limited amount of salt (less than 0.5 g per day) [8]. This diet helped reduce blood pressure in 64% of patients with hypertension and normalize blood pressure in 25% of patients with heart failure. More recent work proves that the main reason for the decrease in blood pressure when following the Kempner diet was precisely the sharp restriction of salt intake [9].

In 2007, the normal daily sodium intake for humans was determined to be from 2.6 to 4.8 g per day [10]. These figures, according to the study's authors, have remained unchanged in 45 countries for 50 years.

Salt consumption peaked in the 1870s, and after the invention of the refrigerator and freezers, the importance of salt as a preservative declined, but recently there has been a resurgence in salt consumption with more salty or processed foods [2].

However, not all people with regular high salt intake develop A.G. The whole point, as it turned out, is individual “sensitivity” to salt. The concept of salt sensitivity was originally proposed in the late 1970s, but the phenomenon is the subject of modern research that supports this theory. Some people may have increased sensitivity to salt, and when they consume it in excess, they develop hypertension. In others who are not sensitive, blood pressure remains normal even when consuming foods high in sodium. Salt sensitivity, as the author further notes, is a common biological phenomenon in human society. Depending on the method of determination and measurement, increased sensitivity to salt was noted in 25-50% of people with normal blood pressure and in 40-75% of patients with hypertension [11].

Active study of salt intake and its relationship with health began in the 1960s, when L. Dahl published the results of cross-population studies in the form of a now well-known graph (Fig. 1),

Rice. 1. Linear relationship between salt intake and blood pressure in different populations. which represents the entire spectrum of salt consumption around the world. The graph shows the influence or direct dependence of the spread of elevated blood pressure on the amount of salt consumed, which makes an important contribution to the salt hypothesis of increased blood pressure. The presented data leave no doubt that high blood pressure does not occur or is extremely rare in those regions where the population consumes small amounts of sodium throughout their lives (for example, Eskimos), and is often observed in areas where they consume a lot of salt (more than 20 g/day), as, for example, in the North of Japan, where elevated blood pressure is observed in 40% of the population. Differences in the prevalence of hypertension in countries or regions with high salt consumption were proven in more recent studies, which confirmed the assumption that it is the sodium content in food that is the main factor determining the incidence of hypertension in the population. It is possible, as the authors of more recent studies note, that other factors, such as obesity, race, constitutional characteristics, and dietary patterns, also affect blood pressure levels, as well as the amount of sodium consumed [12]. The results of a prospective 3-year study conducted in Russia showed that when salt intake was reduced from an average of 12 to 6 g per day, a statistically significant decrease in blood pressure in women with high normal blood pressure over 3 years was 3.27 mmHg. for systolic blood pressure (SBP) and 2.09 mm Hg. for diastolic blood pressure (DBP) [3]. In men, a more modest decrease in blood pressure was noted: SBP decreased by 1.92 mm Hg, and DBP by 1.91 mm Hg. With an increase in salt intake, blood pressure, on the contrary, increases. The Intersalt study estimated that salt intake greater than 6 g/day over 30 years would increase SBP by 9 mmHg. [13].

How much salt does the body need?

In the Stone Age, people consumed a minimal amount of salt; their diet consisted of natural, fresh foods. Currently, in North America there are surviving tribes of Indians leading a primitive way of life. Their daily sodium intake turned out to be 20 times less than that of people living in developed countries and eating mainly processed, refined foods. It is noteworthy that the blood pressure in Indians averaged 96/60 mmHg. and did not increase with age, which is not typical for modern civilizations.

The results of epidemiological studies around the world show that the optimal daily requirement for salt is 6-7 g, the so-called. approximately half of the amount consumed in modern society [13].

It is extremely difficult to accurately estimate the amount of sodium consumed daily, since even 24-hour urinary sodium excretion (the method considered the gold standard for determining daily salt intake) varies widely among individuals. M. Alderman [14] believes that there is no evidence that reducing salt intake to 3.5 g per day will improve health outcomes. And in 2013, the Institute of Medicine recognized sodium intake of up to 1.5 g per day as adequate [15].

The mechanism by which blood pressure increases with excess sodium intake remains unclear. It has been shown that in hypertension the flow of sodium and potassium through the erythrocyte membrane is disrupted. Due to disturbances of the potassium-sodium pump in hypertension, the sodium content in the intercellular space of smooth muscle tissue increases. This leads to increased excitability of the latter, which can cause an increase in blood pressure [16].

In the introduction to their work, L. Dahl et al. [1] state that salt is harmful and that the need for salt is less than the actual consumption. It's right. Most people eat more salt than necessary.

How to reduce salt intake?

For several million years, the ancestors of modern humans, like all mammals, ate foods low in salt. In table 1 presented

Table 1. Average salt content per 100 g of product, salt content in basic foods. From the data in table. 1 shows that the least amount of salt (and therefore sodium) is found in fresh vegetables and fruits.

In 2003, WHO recommended limiting salt intake in adults to 5 g per day (or 2 g sodium per day) [17]. Since then, these figures have been repeated in all the recommendations that we use to this day, including for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases [18].

Patients with hypertension are advised to sharply limit salt intake. This is achieved by following several rules proposed in 2000 and thanks to which you can reduce your daily salt intake by almost 2 times [14]:

- reduce the addition of salt when cooking by 50%,

- replace canned food with natural products,

- do not add salt to food while eating,

- reduce consumption of pickles,

- use unsalted seasonings,

- Avoid taking antacids due to the sodium they contain.

It seems so easy to reduce your salt intake by following these simple rules, but our contemporaries continue to eat more salt than is recommended by the medical community.

Why do we eat a lot of salt?

Although WHO recommended reducing salt intake for all adults back in 2003, actually reducing salt intake is difficult to achieve. Here's why: Due to sodium deficiency over a long period, from the Stone Age to the present day, people have developed a powerful salt appetite. This innate desire for salty foods makes it difficult in practice to reduce salt in the diet. However, when salt consumption is reduced (particularly in older people), due to a sharp change in taste habits, a person may lose his appetite altogether.

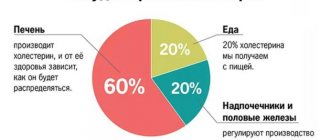

Humanity uses salt as needed to preserve food to avoid food poisoning, as salt is known to be a natural, effective and safe preservative. The fact is that 80% of salt consumed (Fig. 2)

Rice. 2. “Hidden salt” in food. Adapted from F. He and G. MacGregor, 2009 accounts for the so-called “hidden” salt that is found in all industrially processed foods where salt is added for longer storage. The review authors blame manufacturers for adding too much salt to make a profit [19]. When salt is added to meat products, their weight increases, since salt is capable of retaining water, and as a result, manufacturers make a profit without special costs. It is estimated that the mass of a product can be increased by 20% completely free of charge using salt and water. The amount of salt in industrially processed foods is mainly due to the fact that it makes cheap, unpretentious food edible at no cost. Heavily salted foods are in high demand due to the salty taste habit - and this also increases the profits of producers. With the constant consumption of salty food, thirst arises, which contributes to the consumption of soft drinks and mineral water, which also cause thirst, i.e., a vicious circle arises for buyers and increased profits for producers. Food manufacturers attribute the addition of too much salt to consumer preference and report that if the salt content is reduced, consumers will avoid purchasing. However, this does not take into account a very important factor: only 1-2 months pass from a change in the sensitivity of taste buds in the oral cavity to a decrease in salt concentration [20]. This means that a lower concentration of salt will still be perceived as salty. There is evidence that if salt intake is reduced, people will prefer foods with less salt and may be able to avoid the highly salty foods they previously ate [21]. In the experience of UK consumers, reducing the salt in a particular brand's staple products did not reduce sales and there were no complaints from customers regarding taste. Therefore, it is unlikely that reducing the salt concentration in food products will lead to abstinence from purchases. But salt is a major contributor to thirst, and any reduction in salt intake will reduce fluid intake with a consequent reduction in sales of soft drinks and mineral water, and some of the world's largest salty snack companies are part of soft drink companies.

Less is better?

Do I still need to reduce my salt intake? The main focus of the study of salt intake has been on its beneficial effects on blood pressure. Currently, there is growing evidence of another, negative effect of reducing salt on health, which is in no way related to blood pressure. By 2013, the results of studies on the impact of salt reduction on health indicators and the idea of an additional reduction of salt in the diet of all adults, including those who do not suffer from or are at risk of developing hypertension, were published. In the same year, a special committee of the Institute of Medicine, after analyzing the research results, published a report in which it expressed its opinion on this matter [15].

1. There is no evidence of an effect of modest reductions in blood pressure with reduced salt intake on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

2. The benefits of reducing salt for the entire population have not been proven.

3. There is a safe range (just a range, not a 5 g point) for salt intake.

4. The benefits or harms of sodium intake less than 2300 mg/day (5 g salt) have not been established, but there are concerns about sodium intake below 1.5 g/day (3 g salt).

Before changing recommendations to an even lower salt intake due to proven effective lowering of blood pressure, it is necessary to understand that a person may suffer not only from increased blood pressure, but also from other diseases, metabolic disorders, or, finally, just be healthy [7]. Thus, in a study involving patients with heart failure (HF), a deterioration in the course of the disease was noted in the group with salt restriction to 1-1.7 g per day: re-hospitalization was more often required and an increase in mortality was observed within 6 months from the start of the study compared with group consuming 2-4.7 g per day. Therapy S.N. was the same in both groups. A deterioration in the course of diabetes mellitus types 1 and 2 was also noted [22]. A recently published review demonstrated a decrease in blood pressure by 1% in normotensive patients and by 3.5% in patients with hypertension, while at the same time a significant increase in plasma hormones (Table 2):

Table 2. Increase in hormone levels with decreased salt intake (adapted from N. Graudal et al., 2012) Note. Here and in the table. 4: *p<0.05 – statistically significant values. renin, aldosterone, adrenaline, norepinephrine. The demonstrated increase in adrenaline and norepinephrine is statistically insignificant, since, as can be seen from the data in table. 2, there was an insufficient number of participants and the studies themselves. From the data in table. 3 is visible

Table 3. Increase in lipid levels with decreased salt intake (adapted from N. Graudal et al., 2012) that the increase in cholesterol by 2.5%, plasma triglycerides by 7% is significant (

p

< 0.05), and high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and low (LDL) - statistically unreliable for the same reason (insufficient participants and studies to detect statistical significance) [23]. Moreover, as noted by F. He et al. [5], the adverse effects on lipids, especially triglyceride levels, are not simply an acute effect on salt reduction, as previously thought, but are persistent and long-term.

How does the ancient health science of Ayurveda evaluate salt? The salty taste will help drive away melancholy and allow you to feel the joy of life, no matter what it is.

In this regard, we can note a study on the effect of salt reduction on psychological status. In 2015, Japanese scientists published the results of a study in which 1,014 adult men reduced their salt intake from 10.8 g per day (4.3 g sodium) to 7 g salt, or 2.8 g sodium, per day, which caused development of depression [24].

Reducing dietary salt intake leads to a decrease in blood pressure, but the possibility of a negative effect of low salt intake on health cannot be ignored, excluding A.G. To recommend salt restriction for all healthy adults below 3 g of sodium (i.e., less than 6 g of salt or less than 1 teaspoon) requires a comprehensive weighing of the benefits and risks of this measure, which requires studies involving large populations. Although there are doubts about the benefits of reducing salt intake for all people, reducing salt intake is now an adjunct to drug treatment of hypertension and contributes to improved BP control, which reduces the need for medications. In table 4 indicated

Table 4. Contents of daily salt intake in food products (for persons from 19 to 65 years old) a list of products that cover the daily salt requirement.

It is necessary to consider the impact of reducing salt in the diet (in addition to lowering blood pressure) on other health indicators. So, in Fig. 3 shown

Rice.

3. Salt intake and mortality from stroke, heart attack and hospitalization for HF. U

-shaped curve that shows that both high and low salt intake increases cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rates, stroke, myocardial infarction, and hospitalizations for congestive heart failure.

Results from several (but not all) observational studies have shown an increase in mortality not only at “higher levels” but also at levels below 2300 mg, indicating a U

-shaped relationship between sodium intake and mortality [25].

Randomized studies, carefully selected for statistical analysis, have shown the effect of sodium reduction on blood pressure not only in patients with hypertension, but also in healthy people with normal blood pressure (about 1 mm Hg) [25]. The immediate question is whether this effect is beneficial for the population as a whole in terms of morbidity, CVD prevention and mortality, and whether it is possible that these unproven assumptions about the benefits of salt restriction should lead to recommendations for reducing sodium intake in the entire population. The answer to this question can be found in the Institute of Medicine report cited above, one of the main points of which is to warn against further reduction of salt, i.e. below 3 g or below 1.5 g of sodium. The authors of several reviews are sincerely disappointed that the negative consequences of reducing salt intake in healthy people for the prevention of CVD, more precisely the deterioration of lipid and hormonal profiles, were ignored, and that recommendations for reducing salt in the diet remained the same [25–28]. To address the issue of reducing salt intake below 5 g per day, it would be advisable to conduct a large-scale, long-term, randomized clinical trial to determine whether such restrictions provide health benefits or not, and how this restriction affects survival and quality of life. Until the results of such a study are received, it is premature to talk about further reduction of salt in the diet. Many doubt whether it is even worth talking about reducing salt in the diet if the results of lowering blood pressure are so modest [9].

In most countries, more than ½ salt comes from industrially processed foods, including processed foods and sauces. In this regard, gradual, sustainable reduction of salt in processed foods is one of the easiest dietary changes to implement, as it does not require consumers to change their diet and still allows them to achieve the recommended 5 g per day [20].

In z

In conclusion, it should be noted that dietary recommendations for reducing salt must reflect the full variety of health consequences of this measure, including the impact on quality and life expectancy, and since we do not yet have such knowledge, no dietary recommendations can be scientifically justified [26 ]. There is no common point of view on additional reduction of salt in the diet of the population. Discussions are ongoing; the issue of reducing salt intake in order to prevent CVD for the entire population, including healthy people, has not yet been reached.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions:

Concept – O.M.

Collection and analysis of material - O.M., A.B.

Editing - O.M., A.B., E.P.

Sodium is normal in blood serum. Checking your body's sodium levels

Sodium is an element that is present in bones, inside cells, and in blood and other fluids. Most of it is in the blood serum, so to determine the level of sodium in the human body, a test is performed to measure the concentration of electrolytes in the blood (ionogram). This test involves taking a blood sample and then measuring the patient's electrolyte levels:

- sodium;

- potassium;

- magnesium;

- calcium;

- phosphate ions;

- chlorine ions.

You don't have to order everyone to be tested, just your sodium level can be tested.

Testing your electrolyte levels is most often ordered when your doctor suspects dehydration or illnesses related to sodium imbalances in the body. Recommended for cardiac patients taking medications that increase urine production and excretion, as well as for chronic diseases with symptoms such as irregular blood pressure or heart problems. Measuring serum sodium does not require special preparation. It is best to go for the test in the morning (7:00 - 10:00), since the examination is carried out on an empty stomach or at least 8 hours after the last meal.

If your sodium ionogram is less than 136 mmol per liter of blood, it means you have low sodium levels in your body. On the other hand, a situation where the sodium concentration clearly exceeds 145 mmol in 1 liter of blood suggests its excess. Electroionogram interpretation should always be performed by a physician. Only he can correctly assess whether a given result is truly associated with abnormal amounts of sodium and other electrolytes in the body.

Interpretation:

- Profuse sweating, prolonged hyperpnea, vomiting, diarrhea, diabetes insipidus, diabetic acidosis, hyperaldosteronism, Cushing's syndrome, dehydration, salt overload of the body.

- Salt-free diet, results of vomiting, diarrhea, excessive sweating with adequate water and inadequate salt replacement, diuretic abuse, polycystic disease and kidney medulla cysts, chronic pyelonephritis, renal tubular acidosis, osmotic diuresis, metabolic acidosis, primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency; congenital adrenal hyperplasia with 21-hydroxylase deficiency, isolated hypoaldosteronism, pseudohypoaldosteronism, edema, ascites, hypothyroidism; hyperosmolarity; SIADH, which may be associated with lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, central nervous system diseases, lung infections, acute intermittent porphyria, psychogenic polydipsia, false hyponatremia with extremely significant hypertriglyceridemia or hyperproteinemia; hyperglycemia.

Sample result (PDF)