Life is a continuous process of exchange, transformation of substances and energy. A variety of pathological factors can disrupt this process, which is accompanied by disorders of the organs and systems of the body. The disease develops. If in these cases the body’s compensatory reactions are exhausted or do not have time to react, a threat to its vital functions arises (terminal state).

- Terminal states

- Stages and stages of resuscitation

- Treatment after resuscitation

Terminal states

With the help of intensive therapy and the use of resuscitation measures, in many cases it is possible to prevent and eliminate the energy and structural deficit that develops in the body during terminal conditions, and save it from death.

Intensive therapy is a set of methods for temporary artificial replacement of vital body functions, aimed at preventing the depletion of adaptive mechanisms and the occurrence of a terminal condition.

Reanimatology is the science of reviving the body; prevention and treatment of terminal conditions (according to V.A. Negovsky).

For human life to exist, it is necessary that oxygen continuously enters and is consumed by cells and carbon dioxide is released from it. These processes ensure the coordinated functioning of the respiratory and circulatory organs under the control of the central nervous system. Therefore, their defeat leads to death (“the gates of death” - as defined by the ancients - the lungs, heart and brain).

Stopping vital activity (death) can occur suddenly (in accidents) or predictably, as a natural consequence of old age or an incurable disease. During a long process of dying, the following stages are noted.

Peredagonia . The physiological mechanisms of the body’s vital functions are in a state of deep exhaustion:

- the central nervous system is depressed, possibly comatose;

- heart activity is weakened, the pulse is thready, systolic blood pressure is reduced to a more critical level (70 mm Hg);

- external breathing is weakened, ineffective: tidal volume and frequency are inadequate;

- the functions of parenchymal organs are impaired.

Peredagonia can take several minutes, hours, or even days. During this time, the patient's condition worsens even more and ends with a terminal pause. The patient loses consciousness, blood pressure and pulse are not determined; breathing stops, reflexes are absent. The terminal pause lasts up to a minute.

The next stage of dying is agony (struggle). Due to the depletion of higher-order vital activity centers (CNS), the bulbar centers and reticular formation go out of control (activate). The patient's muscle tone and reflexes are restored, external breathing appears (random, with the participation of auxiliary muscles). The pulse is palpated above the main arteries, vascular tone can be restored - systolic blood pressure increases to 50 - 70 mm Hg. However, at this time, metabolic disorders in the body's cells become irreversible. The last reserves of energy accumulated in high-energy connections quickly burn out and after 20 - 40 seconds clinical death occurs.

In a number of pathological situations (drowning, electric shock and lightning, being hit by a car, strangulation asphyxia, myocardial infarction, etc.), clinical death can befall the victim unexpectedly, without preliminary manifestations of dying.

The main signs of clinical death:

- absence of pulsation over the main arteries (carotid and femoral);

- persistent pupil dilation with absence of photoreaction;

- lack of spontaneous breathing.

Auxiliary signs:

- change in skin color (dead gray or bluish);

- lack of consciousness;

- lack of reflexes and loss of muscle tone.

An important factor influencing the effectiveness of resuscitation in case of clinical death is the ambient temperature and the duration of dying. In case of sudden cardiac arrest, clinical death in conditions of normothermia lasts up to 5 minutes, at sub-zero temperatures - up to 10 minutes or more. A long period of dying significantly worsens the effectiveness of resuscitation, reducing the period of clinical death. Biological death occurs when, as a result of irreversible changes in the body, and above all, in the central nervous system, a return to life is impossible.

Stages and stages of resuscitation

A set of emergency measures carried out to patients in a state of clinical death, aimed at restoring the body’s vital functions and preventing irreversible damage to its organs and systems, is called resuscitation. The person who revives the victim is called a resuscitator.

Returning a patient to a full life from a state of clinical death is possible only with a qualified and consistent implementation of a complex of resuscitation measures.

The first stage of resuscitation is the provision of first aid (basic life support) carried out by a resuscitator (not necessarily a medical worker, but every trained person who has basic resuscitation skills). After clinical death is declared (which should take no more than 7-8 seconds!), preparatory measures are immediately carried out: the victim is laid on his back, preferably with the upper part of his body lowered, on a solid base. A savior who is not involved in intensive care lifts the victim’s legs 50–60 cm upward to drain blood from them and increase blood supply to the cavities of the heart.

The first stage of resuscitation is to ensure airway patency. The resuscitator performs a “triple technique” (according to P. Safar):

a) opens the victim’s mouth and with a finger wrapped in a handkerchief (gauze cloth for clamps) frees him from foreign bodies and liquids (vomit, sputum, algae, inserted crevices, blood clots, etc.);

b) tilts the victim’s head as far back as possible, placing an improvised cushion under the neck (for example, the forearms). In this case, in most victims, the upper respiratory tract is freed from the tongue and its root, becoming open;

c) brings the lower jaw forward. The patency of the upper respiratory tract is restored in other cases.

The second stage of resuscitation is performing mouth-to-mouth artificial ventilation. Having covered the victim's mouth with a bandage (handkerchief), the resuscitator tightly covers his mouth with his lips and exhales. Mandatory condition: the victim's head is tilted back, his nostrils are pinched with the thumb and forefinger (so that the air does not return back), the exhalation volume for adults should be 800 - 1000 ml. When blowing air, the resuscitator, out of the corner of his eye, watches the movements of the victim’s chest, which should rise and fall. Having made 2 - 3 exhalations, the savior begins to carry out the next stage of resuscitation.

The third stage of resuscitation is closed cardiac massage. Being on the side of the victim, the resuscitator places one hand on the lower third of the sternum, strictly in the middle, so that the fingers are raised up and placed parallel to the ribs. He places the second hand on top and, pressing rhythmically, moves the sternum in the sagittal direction to a depth of 3 - 5 cm. The frequency of pressing is 60 per minute.

Mandatory condition: when pressing on the sternum, the fingers of the hand should be raised up to prevent fractures of the ribs, and the arms should be straightened at the elbow joints. Cardiac massage is thus carried out by the mass of the resuscitator’s torso. Subsequently, the rescuer alternately injects air and presses on the sternum in a ratio of 1: 4. If there are two resuscitators, each of them performs its own stage of resuscitation. If necessary, each time remove the lower jaw to ensure patency, breathe in the 2nd and 3rd stages in a ratio of 2: 10.

Signs of effective resuscitation measures :

- constriction of the pupils,

- normalization of skin color,

- feeling under the fingers of arterial pulsation, synchronous with the massage;

- Sometimes blood pressure is determined.

In some cases, cardiac activity may be restored. The first stage of resuscitation should be carried out continuously until the arrival of a specialized medical team.

The second stage of cardiopulmonary resuscitation is the provision of specialized medical care (further life support). It is carried out by professional doctors using monitoring, diagnostic, therapeutic equipment and medications. Under the control of a laryngoscope, a portable or electric suction is used to better clean the airways and intubate the trachea.

The resuscitation team provides more effective artificial ventilation of the lungs - with a manual portable or stationary ventilator through a mask, air duct or endotracheal tube with an air-oxygen mixture. If you have a special massager, you can perform closed cardiac massage using hardware.

At this stage, the following stages of resuscitation are carried out alternately. The first stage is drug therapy. For all types of circulatory arrest, solutions of adrenaline hydrochloride (1 ml of 0.1% solution) and atropine sulfate (3 ml of 0.1% solution) are used. The second stage is assessing the type of circulatory arrest. For adequate drug therapy, it is necessary to diagnose the functional state of the victim’s heart. To do this, the patient is connected to an electrocardiograph (cardioscope) in the second lead and the curve is recorded.

There are the following types of circulatory arrest : asystole, fibrillation, “ineffective heart”.

- During asystole, the electrocardiograph records a straight line.

- Ventricular fibrillation is manifested by frequent chaotic contraction of individual myocardial fibers (uneven “teeth” of high, medium and variable amplitude).

- “Ineffective heart” - registration of the ventricular complex on the ECG in patients with absent pumping function of the heart.

Ventricular fibrillation and an “ineffective heart” without appropriate correction, as the energy resources of the myocardium decrease, quickly turn into asystole. In the presence of high-wave fibrillation, you can use a 2% lidocaine solution (0.5 mg per 1 kg of body weight, repeatedly).

In case of an “ineffective heart” caused by a sharp decrease in the volume of circulating blood, to ensure its pumping function, hemodynamic media (refortan, stabizol, polyglucin, rheopolyglucin), crystalloids, and glucocorticoids are infused intravenously or intraarterially; in case of massive blood loss - canned blood and its components.

In case of cardiac arrest caused by hyperkalemia or hypocalcemia (acute and chronic renal failure, hemolysis of red blood cells, massive tissue destruction, hypoparathyroidism), calcium chloride should be used (5 - 10 ml of 10% solution, intravenously). Medicinal media are administered intravenously, into the lumen of the trachea, through a cannulated artery, intracardiacly.

Medians administered intravenously, with effective cardiac massage, enter the coronary vessels, exerting their influence on the heart. If it is impossible to provide venous access, the intratracheal method is used, which is no less effective. In this case, with a needle for intramuscular injections, the cricothyroid ligament or the space between the tracheal rings is pierced and solutions of adrenaline, atropine or lidocaine are injected (2-3 ml of 0.1% solution of adrenaline hydrochloride, 1 ml of 0.1% solution of atropine sulfate, 2 ml of 2% lidocaine solution - diluting them in 10 ml of sodium chloride solution). These medications can also be given through an endotracheal tube. During ventilation of the lungs at this time, medicinal media penetrate through the alveoli, and after 30-40 seconds enter the lumen of the coronary vessels.

According to some researchers, using distilled water as a solvent can achieve effective absorption of the solution from the alveoli into the blood due to the difference in osmotic pressure. Due to the large number of complications, intracardiac administration of drugs is used less and less (the technique is described below).

The intra-arterial method of infusion in patients with a significant loss of circulating blood volume (for example, with hemorrhagic shock and an “ineffective heart”) also deserves attention Infusion of blood and other agents into a catheterized artery (eg, radial) is often effective in filling the coronary arteries with blood, ensuring efficient cardiac function and restoring hemodynamics.

The third stage is electrical defibrillation of the heart. It is used in patients with ventricular fibrillation (the method is described below). In an operating room, it is sometimes more effective to perform open cardiac massage. Indications: cardiac arrest during surgery on the organs of the chest and upper abdomen; cardiac tamponade; bilateral pneumothorax; multiple fenestrated rib fractures; congenital and acquired deformities of the chest, which make it impossible to conduct effective closed massage. Open massage is carried out through transthoracic or subdiaphragmatic access, without opening or with opening of the cardiac membrane.

A prerequisite for this is that the fingers of one or both hands, when squeezing the ventricles, should be placed along the vascular bundle so as not to pinch it. The third stage of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

EFFECTIVENESS OF RESUSCITATION MEASURES IN A HOSPITAL

Published in 2015, Issue June 2015, MEDICAL SCIENCES | No comments yet

Grachev S.S.1, Evtushenko S.V.

1Candidate of Medical Sciences, Belarusian State Medical University

EFFECTIVENESS OF RESUSCITATION MEASURES IN A HOSPITAL

annotation

This scientific article presents the analysis, tactics and procedure for resuscitation measures in accordance with the recommendations of the European Resuscitation Council. The authors analyze the implementation of resuscitation measures using the example of a multidisciplinary clinical hospital. Despite these recommendations, inconsistencies were identified in the procedure and tactics of resuscitation.

Key words : resuscitation, asystole, ventricular fibrillation, effectiveness of resuscitation, circulatory arrest.

Gratchev SS1, Evtushenko SV

1PhD in Medical Sciences, Belarusian State Medical University

INHOSPITAL RESUSCITATION EFFICIENCY ANALYSIS

Abstract

This research article presents the analysis, tactics and procedures for resuscitation in accordance with the recommendations of the European Resuscitation Council. The author analyzes resuscitation on the example of multidisciplinary clinical hospital. In spite of these recommendations it has been identified inconsistencies in the procedure for resuscitation and tactics.

Keywords : resuscitation, asystolia, ventricular fibrillation, the effectiveness of resuscitation, cardiac arrest.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has been proposed as a method of temporarily maintaining circulation in otherwise healthy people during sudden cardiac death. Currently, less than half of patients treated with CPR achieve cardiac recovery, and less than half survive and are discharged from hospital [2]. At the same time, half of the discharged patients suffer from significant neurological impairment, often so severe that it prevents the person from leading an independent life. Thus, less than 5% of all those who receive CPR are able to live it normally after discharge.

The likelihood of success of CPR when the patient leaves the hospital without neurological damage depends on the condition of the patients who were resuscitated, the length of the interval between cardiac arrest and the start of resuscitation, and the duration of CPR required to restore circulation [1,2].

Because survival declines exponentially as the time from cardiac arrest to resuscitation increases, the greatest success has been achieved in those patients who received CPR within 5 to 10 minutes of death [4]. In most patients who can be revived, resuscitation will be successful if basic techniques are quickly applied [4].

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation initially restores circulatory function in 40-50% of patients who are started on resuscitation. This percentage is lower for sudden death outside a hospital and higher in a hospital setting, especially if cardiac and respiratory arrest occurs in the intensive care unit. As already noted, of all patients with restored cardiac function, 60 to 80% survive longer than 24 hours, but at best, 25% of those undergoing resuscitation leave the hospital, and many of them have neurological impairment. Concomitant pathology before the start of cardiopulmonary resuscitation worsens its results [5]. Duration of ischemia greater than 4 minutes, initial asystole or bradycardia, prolonged resuscitation, low CO2 concentration in exhaled air and the need for vasopressor support after resuscitation are unfavorable prognostic signs [1,2].

Main complications: aspiration pneumonitis, convulsive syndrome associated with cerebral ischemia. About half of patients experience gastrointestinal bleeding due to stress ulcers. After resuscitation, there is often a significant increase in liver and/or muscle enzymes. Liver and aortic injury, pneumothorax, rib and sternum fractures can also occur during CPR, and are especially common if improper sternal compression technique is used [3,6,7].

One of the main goals of CPR is to fully restore brain function. After “successful” resuscitation, approximately half of the victims do not regain consciousness. Of the patients in whom consciousness is restored, approximately 50% develop severe persistent neurological deficit due to acute cerebrovascular accident, such as acute posthypoxic encephalopathy, convulsive states, paralysis, paresis, cognitive impairment, and vegetative state. The likelihood of regaining consciousness after cardiac arrest, highest in the first 24 hours after resuscitation, subsequently decreases exponentially to a very low level. In the initial post-resuscitation period, the absence of pupillary and oculomotor reactions is the most reliable predictor of a poor neurological prognosis. It is rarely possible to revive a patient if resuscitation efforts require more than 20–30 minutes. The most notable exception to this rule is hypothermic victims, who can sometimes be successfully revived after several hours of resuscitation efforts [4,5].

The variety of possible causes of cardiac arrest requires methodically developed analysis of the situation and techniques for managing the patient. In 2010, the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) grouped all cardiac causes of cardiac arrest into two main groups. Arrest of effective circulation due to ventricular fibrillation (VF) or ventricular tachycardia (VT), as well as arrest of effective circulation due to asystole, bradyarrhythmia or electromechanical dissociation (EMD) [6,7]. According to the ERC-2010 recommendations, the algorithm for resuscitation of patients with VF/VT must include electrical pulse therapy (EPT) from the very beginning of resuscitation efforts. In case of asystole/bradyarrhythmia/EMD, EIT is not indicated [4,6,7].

Indications for cessation of resuscitation measures are the appearance of signs of biological death, as well as the absence on the ECG of signs of electrical activity of the myocardium for more than 30 minutes in the absence of hypothermia [4,6,7].

The purpose of this study was to determine the tactics and effectiveness of resuscitation measures in a multidisciplinary hospital.

Research objectives:

- Conduct an analysis of resuscitation measures based on medical records.

- Identify potential deviations of ongoing resuscitation measures from ERC-2010 recommendations.

- Assess the effectiveness of the resuscitation measures taken.

Materials and methods

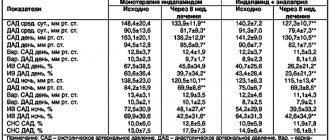

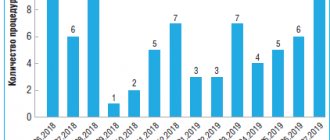

A retrospective analysis of 70 protocols of resuscitation measures was carried out according to the medical records of 62 patients in a multidisciplinary clinical hospital in Minsk for 2013. The causes of primary ineffectiveness of blood circulation, the start time and duration of resuscitation measures, the location, the technique of resuscitation itself, drug therapy and the effectiveness of resuscitation measures were studied. It was assessed whether the resuscitation team adhered to the ERC-2010 recommendations, and how fully and informatively, from the point of view of scientific processing, the resuscitation protocols were drawn up.

Age structure of patients

The study included 62 patients aged 51 years and older.

In the age range from 51 to 60 years, CPR was performed in 9 patients, which was 14.5%, of which 2 were successful resuscitations.

Between the ages of 61 and 70 years, CPR was performed in 13 patients, which was 21.0%, of which 1 was successful.

Between the ages of 71 and 80 years, CPR was performed on 22 patients, which was 35.5%, of which 4 were successful resuscitations.

The age range of more than 80 years included 18 patients, which amounted to 29.0%, of which 1 had successful resuscitation.

Structure of intensive care units

In total, 70 resuscitation measures were carried out at the clinical hospital in question in 2013, of which 18 CPR protocols could not be analyzed, since they did not contain a complete description of resuscitation measures. It was also impossible to determine the time and stages of drug administration. 8 resuscitations were successful, which amounted to 11.4% of all CPR. Of these, 7 deaths (10%) occurred from primary circulatory failure as a result of EMD/asystole/bradyarrhythmia, and 1 death (1.5%) occurred from VF/VT.

Unsuccessful resuscitation accounted for 62 cases, or 88.6%, of which 40 deaths (57.1%) occurred from EMD/asystole/bradyarrhythmia, 4 deaths (5.7%) from VF/VT. As noted, 18 cases, or 25.7%, could not be analyzed.

Analysis of CPR algorithms

In case of death from VF/VT, full compliance with the ERC-2010 algorithms was not observed. None of the resuscitations performed were successful. Analysis of two CPR protocols (4.2% of cases) made it possible to fully confirm the sequence of actions of the team, in accordance with the recommendations of the European Council on Resuscitation in Death from Asystole/Bradyarrhythmia/EMD, of which one resuscitation was successful.

Analysis of CPR protocols for death from VF/VT showed that the most common errors were the following. Inappropriate administration of atropine sulfate at the beginning of CPR or administration of an increased dose of adrenaline was observed in 60% of cases (3 of 5). Early cessation of resuscitation (CPR less than 30 minutes) was recorded in 20% of cases (1 out of 5).

At the same time, resuscitation measures for more than 30 minutes from the moment of asystole, as well as unjustified EIT (in case of registration of asystole, bradyarrhythmia) were observed in 20% of cases. Non-compliance with the time and sequence of drug administration occurred in 80% of intensive care units (4 cases out of 5). EIT for VF/VT was not performed in 4 out of 5 cases.

Analyzing the CPR protocols of patients who died from asystole/bradyarrhythmia/EMD, it was found that in 95.8% the ERC-2010 recommended resuscitation algorithms were also not followed. Thus, unjustified administration of drugs or the introduction of increased doses was noted, as well as unjustified EIT (asystole, bradyarrhythmia) occurred in 12.8% of each case (6 out of 47). Early cessation of CPR (less than 30 minutes) – in 21.3%, which amounted to 10 cases. And finally, non-compliance with the time and sequence of drug administration occurred in 85.1%, which amounted to 40 cases out of 47 resuscitations.

Structure of mortality. Of the 62 patients selected for the study, 53.2% or 33 people died suddenly, 29 people or 46.8% died from decompensation of chronic diseases. 60 resuscitation measures were carried out in the ICU, of which 6 were successful. Outside the intensive care unit, 10 CPR were performed, two of which had a positive result.

conclusions

- In 25.7% of cases, there was incomplete documentation of medical documentation, which did not make it possible to qualitatively analyze the resuscitation care provided to the patient.

- There was insufficient differentiation of terminal conditions requiring EIT, and in most cases there was unjustified administration of drugs during CPR.

- In only two of the 52 analyzed resuscitation protocols, there was full compliance of the actions of the resuscitation team with the recommended ERC-2010 algorithms for providing resuscitation care in the case of asystole/bradyarrhythmia/EMD.

- 50% of resuscitated patients survived to the first period of post-resuscitation illness, and only 25% to the fourth.

Literature

- Bokeria L. A., Chicherin I. N. Efficiency of resuscitation measures using an algorithm that does not include artificial ventilation of the lungs during cardiac arrest in intensive care units in the elderly // “Clinical Physiology of Blood Circulation”. – No. 1. – 2010. – P. 17 – 22.

- Marini J. J., Wheeler A. P. Medicine of critical conditions // M. - “Medicine”. – 2002 – 992s.

- Negovsky V.A., Gurvich A.M. Post-resuscitation disease is a new nosological unit. Reality and significance // Experimental, clinical and organizational problems of resuscitation. – M.: NIIOR, 1996. – P. 3-10.

- Prasmytsky O. T., Rzheutskaya R. E. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: educational method. manual / Mn.: BSMU, 2013. – 36 p.

- Usenko L.V., Tsarev A.V. Cardiopulmonary and cerebral resuscitation: A practical guide. – 2nd ed., rev. and additional – Dnepropetrovsk, 2008. – 47 p.

- Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Soar J., Sunde K., Koster RW, Smith GB, Perkins GD European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 4. Adult advanced life support // Resuscitation. – – V. 81. – P. 1305-1352.

- Koster RW, Bauhin MA, Bossaert LL et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 2. Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillators // Resuscitation. – – V. 81. – P. 1277-1292.

References

- Bokeriya LA, Chicherin IN Effektivnost reanimatsionnykh meropriyaty po algoritmu, ne vklyuchayushchemu provedeniye iskusstvennoy ventilyatsii legkikh, pri ostanovke serdtsa v otdeleniyakh intensivnoy terapii u pozhilykh // “Klinicheskaya fiziologiya krovoobrashcheniya” – No. 1. – 2010. – P. 17 – 22.

- Marini Dzh. Dzh., Uiler AP Meditsina kriticheskikh sostoyany // M. -2002. – 992s.

- Negovsky VA, Gurvich AM Postreanimatsionnaya bolezn – novaya nozologicheskaya edinitsa. Realnost i znacheniye // Eksperimentalnye, klinicheskiye i organizatsionnye problemy reanimatologii. – M.:, 1996. – 3-10.

- Prasmytsky O.T., Rzheutskaya R. Ye. Serdechno-legochnaya reanimatsiya: ucheb.-method. posobiye / Mn.: BGMU, 2013. – 36 p.

- Usenko LV, Tsarev AV Serdechno-legochnaya i tserebralnaya reanimatsiya: Prakticheskoye rukovodstvo. – 2nd izd., ispr. i dop. – Dnepropetrovsk, 2008. – 47 s.

- Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Soar J., Sunde K., Koster RW, Smith GB, Perkins GD European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 4. Adult advanced life support // Resuscitation. – – V. 81. – P. 1305-1352.

- Koster RW, Bauhin MA, Bossaert LL et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 2. Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillators // Resuscitation. – – V. 81. – P. 1277-1292.