Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a disease characterized by the inability of the heart to pump a certain volume of blood sufficient to provide the body with oxygen. CHF can be caused by many diseases of the cardiovascular system, the most common of which include coronary heart disease, hypertension, endocarditis and rheumatoid heart defects. Weakening of the heart muscle leads to the impossibility of normal pumping of blood, as a result of which the amount of blood released into the vessels gradually decreases.

The development of heart failure occurs gradually; in the early stages, the disease can manifest itself only during physical exertion, then it begins to be felt at rest.

The appearance of characteristic symptoms at rest indicates that the disease has entered a severe stage. The progression of chronic heart failure threatens a significant deterioration of the patient’s condition, a decrease in his working capacity and even disability. The development of chronic liver and kidney failure, blood clots, and strokes may occur.

Conducting timely comprehensive diagnostics and competent treatment ensures a slowdown in the development of CHF and the prevention of dangerous complications of this serious disease.

In order to stabilize the condition, a patient diagnosed with “acute and chronic heart failure” must adhere to the correct lifestyle: normalize his weight, follow a low-salt diet, limit physical and emotional stress.

Heart failure

Heart failure is an acute or chronic condition caused by a weakening of myocardial contractility and congestion in the pulmonary or systemic circulation. It manifests itself as shortness of breath at rest or with slight exertion, fatigue, swelling, cyanosis (blueness) of the nails and nasolabial triangle. Acute heart failure is dangerous due to the development of pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock, while chronic heart failure leads to the development of organ hypoxia. Heart failure is one of the most common causes of human death.

Chronic heart failure: recommendations for prevention

Prevention of chronic heart failure is based on the basic principles that every person should adhere to, especially after 40-45 years:

- engage in physical activity regularly;

- control blood pressure;

- lead a lifestyle that prevents the development of coronary artery disease;

- normalize metabolism (reduce excess weight, control cholesterol levels, limit salt intake);

- give up frequent consumption of coffee, alcoholic beverages, quit smoking.

Thanks to the clear and consistent implementation of the above recommendations, it is possible to significantly slow down the pathological process and improve the patient’s quality of life.

Diagnosis and treatment of CHF in Moscow is offered by the Yusupov Hospital Therapy Clinic, a leading multidisciplinary center equipped with the latest equipment. The use of innovative techniques and the vast experience of the clinic’s team of specialists - therapists, cardiologists, diagnosticians - allows us to achieve impressive results in the treatment of chronic heart failure. Each patient at the Yusupov Hospital is provided with professional nursing care. In case of chronic heart failure, not only drug treatment is necessary, but also a review of the diet, which our qualified nutritionists help to cope with, who develop a special nutrition plan for each patient with CHF.

Classification of heart failure

According to the nature of the course, the classification of heart failure involves division into:

- spicy;

- chronic.

Acute heart failure

According to ICD-10, the code corresponds to I50.9 Heart failure, unspecified. Acute circulatory failure often leads to death (death) in the absence of timely, competent therapy.

Acute heart failure occurs suddenly, minutes or hours after a heart attack, when the body can no longer compensate. Some symptoms include:

- severe difficulty breathing and/or coughing;

- Gurgling sound when breathing;

- Heart rhythm disturbances;

- Pallor;

- Cold sweat.

The development of acute heart failure can occur in two types:

- left type (acute left ventricular or left atrial failure);

- acute right ventricular failure.

Chronic heart failure

Chronic heart failure is a consequence of cardiovascular diseases. It develops gradually and progresses slowly. The wall of the heart thickens due to the growth of the muscle layer. The formation of capillaries that supply nutrition to the heart lags behind the growth of muscle mass. The nutrition of the heart muscle is disrupted, and it becomes stiff and less elastic. The heart cannot cope with pumping blood.

Pregnancy with chronic heart failure: disease progression

The body of a pregnant woman has to overcome quite serious loads, including on the heart. Due to intrauterine growth and fetal development, the heart muscle must cope with the circulation of increased blood volume.

In women suffering from certain cardiovascular diseases, this heart function is often impaired, which leads to the development of CHF. The degrees of heart failure manifest themselves in different ways, but if even the slightest discomfort occurs, pregnant women should immediately inform their doctor.

How is chronic heart failure classified?

In all cases when heart failure (symptoms and organ disorders) develops slowly, it is said to be chronic. As symptoms increase, this option is divided into stages. So, according to Vasilenko-Strazhesko there are three of them.

I (initial) stage - hidden signs of circulatory failure, manifested only during physical activity by shortness of breath, palpitations, excessive fatigue; at rest there are no hemodynamic disturbances.

Stage II (severe) – signs of prolonged circulatory failure and hemodynamic disorders (congestion of the pulmonary and systemic circulation) are expressed at rest; severe limitation of working capacity:

- Period II A – moderate hemodynamic disturbances in one part of the heart (left or right ventricular failure). Shortness of breath develops during normal physical activity, and performance is sharply reduced. Objective signs are cyanosis, swelling of the legs, initial signs of hepatomegaly, hard breathing.

- Period II B – deep hemodynamic disorders involving the entire cardiovascular system (large and small circle). Objective signs – shortness of breath at rest, severe edema, cyanosis, ascites; complete disability.

III (dystrophic, final) stage – persistent circulatory and metabolic failure, morphologically irreversible damage to the structure of organs (liver, lungs, kidneys), exhaustion.

Depending on the symptoms that appear at different stages of the disease, the severity of the patient, functional classes (types) of heart failure are distinguished:

I – the disease does not have any effect on the patient’s quality of life. Heart failure is stage 1 and does not limit the patient’s physical activity in any way. Stage 1 deficiency responds well to therapy.

II – the patient is not bothered by anything at rest; mild restrictions are recorded during physical activity.

III – there are no symptoms at rest, but there is a noticeable decrease in performance.

IV – chest pain and signs of heart failure are recorded at rest, the patient is partially or completely incapacitated.

Symptoms of heart failure

In the initial stages, symptoms of heart failure occur only during physical activity. Shortness of breath appears - breathing becomes too frequent and deep, and does not correspond to the severity of work or physical exercise. If the pressure in the vessels of the lungs increases, the patient is bothered by a cough, sometimes with blood.

After physical exertion, heavy meals and in a lying position, increased heart rate occurs. The patient complains of increased fatigue and weakness.

Over time, these symptoms intensify and begin to bother you not only during physical work, but also at rest.

Many patients with heart failure have decreased urine output and go to the toilet mostly at night. In the evenings, swelling appears on the legs, at first only on the feet, and over time it “rises” higher. The skin of the feet, hands, earlobes and tip of the nose takes on a bluish tint. If heart failure is accompanied by stagnation of blood in the liver vessels, a feeling of heaviness and pain occurs under the right rib.

Over time, heart failure leads to poor circulation in the brain. The patient becomes irritable, quickly gets tired during mental stress, and often becomes depressed. He sleeps poorly at night and is constantly sleepy during the day.

Symptoms of right ventricular acute heart failure are caused by stagnation of blood in the veins of the systemic circulation:

- Increased heartbeat is the result of deterioration of blood circulation in the coronary vessels of the heart. Patients experience increasing tachycardia, which is accompanied by dizziness, shortness of breath and heaviness in the chest.

- Swelling of the neck veins, which increases with inspiration, is explained by an increase in intrathoracic pressure and difficulty in blood flow to the heart.

- Edema. A number of factors contribute to their appearance: slower blood circulation, increased permeability of capillary walls, interstitial fluid retention, and impaired water-salt metabolism. As a result, fluid accumulates in cavities and limbs.

- A decrease in blood pressure is associated with a decrease in cardiac output. Manifestations: weakness, pallor, increased sweating.

- There is no congestion in the lungs.

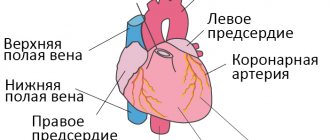

Chronic heart failure develops in the right and left atrial, right and left ventricular types. Chronic heart failure, according to various authors, is observed in 0.5–2% of the population. The incidence increases with age; after 75 years, the pathology occurs in 10% of people. Chronic left ventricular failure develops as a complication of coronary heart disease, arterial hypertension, mitral valve insufficiency, aortic disease and is associated with stagnation of blood in the pulmonary circulation. It is characterized by gas and vascular changes in the lungs.

Clinically manifested:

- increased fatigue;

- dry cough (rarely with hemoptysis);

- attacks of palpitations;

- cyanosis;

- attacks of suffocation, which often occur at night;

- shortness of breath.

In chronic left atrial insufficiency in patients with mitral valve stenosis, congestion in the pulmonary circulation system is even more pronounced. The initial signs of heart failure in this case are cough with hemoptysis, severe shortness of breath and cyanosis. Gradually, sclerotic processes begin in the vessels of the small circle and in the lungs. This leads to the creation of an additional obstacle to blood flow in the pulmonary circle and further increases the pressure in the pulmonary artery basin. As a result, the load on the right ventricle increases, causing the gradual formation of its failure.

Chronic right ventricular failure usually accompanies emphysema, pneumosclerosis, mitral heart defects and is characterized by the appearance of signs of blood stagnation in the systemic circulatory system. Patients complain of shortness of breath during exercise, enlargement and distension of the abdomen, a decrease in the amount of urine discharge, the appearance of edema of the lower extremities, heaviness and pain in the right hypochondrium.

CHF: symptoms

The clinical picture of CHF is quite diverse and depends on the severity and duration of its course. The disease develops slowly over several years. Lack of treatment threatens serious deterioration of the patient's condition.

Most often, chronic heart failure is manifested by the following symptoms:

- shortness of breath during physical exertion, when the patient moves to a supine position, and later at rest;

- dizziness, fatigue and weakness;

- nausea and lack of appetite;

- swelling of the lower extremities;

- development of ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity);

- weight gain due to swelling;

- fast or irregular heartbeat;

- dry cough with pinkish sputum;

- decreased intelligence and attention.

Causes of heart failure

The main causes of heart failure are:

- coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction;

- dilated cardiomyopathy;

- rheumatic heart defects.

In elderly patients, the causes of heart failure are often type II diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension. Type 2 diabetes mellitus can lead to the development of heart failure.

There are a number of factors that can reduce the compensatory mechanisms of the myocardium and provoke the development of heart failure. These include:

- pulmonary embolism (PE);

- severe arrhythmia;

- psycho-emotional or physical stress;

- progressive coronary heart disease;

- hypertensive crises; acute and chronic renal failure;

- severe anemia;

- pneumonia; severe ARVI;

- hyperthyroidism;

- long-term use of certain medications (adrenaline, ephedrine, corticosteroids, estrogens, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs);

- infective endocarditis;

- rheumatism; myocarditis;

- a sharp increase in the volume of circulating blood due to incorrect calculation of the volume of intravenously administered fluid;

- alcoholism;

- rapid and significant weight gain.

Eliminating risk factors can prevent the development of heart failure or slow its progression.

Chronic heart failure: risk group

The following risk factors, or at least one of them, can provoke the development of CHF. When several factors are combined, the likelihood of chronic heart failure increases significantly.

The risk group for the development of CHF includes patients suffering from the following diseases:

- cardiac ischemia;

- history of myocardial infarction;

- high blood pressure;

- heart rhythm disturbance;

- diabetes;

- Congenital heart defect;

- frequent viral diseases;

- chronic renal failure;

- alcohol addiction.

How is heart failure diagnosed?

Diagnosis begins with a comprehensive assessment of a person's medical history, paying particular attention to symptoms (onset, duration, manifestation). This helps classify the severity of the symptom. The heart and lungs are examined. If a heart attack or rhythm disorder is suspected, a 12-lead resting ECG is performed. In addition, echocardiography and complete blood count. The need for catheterization is determined individually.

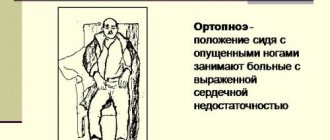

In diagnosis, you need to start with analyzing complaints and identifying symptoms. Patients complain of shortness of breath, fatigue, and palpitations.

The doctor asks the patient:

- How does he sleep?

- Has the number of pillows changed over the past week?

- Did the person begin to sleep sitting instead of lying down?

The second stage of diagnosis is a physical examination, including:

- Skin examination;

- Assessment of the severity of fat and muscle mass;

- Checking for edema;

- Pulse palpation;

- Palpation of the liver;

- Auscultation of the lungs;

- Auscultation of the heart (1st sound, systolic murmur at the 1st point of auscultation, analysis of the 2nd tone, “gallop rhythm”);

- Weighing (a 1% decrease in body weight over 30 days indicates the onset of cachexia).

If heart failure is suspected, the electrolyte and gas composition of the blood, acid-base balance, urea, creatinine, cardio-specific enzymes, and indicators of protein-carbohydrate metabolism are determined.

Based on specific changes, an ECG helps to identify hypertrophy and insufficiency of blood supply (ischemia) of the myocardium, as well as arrhythmias. Based on electrocardiography, various stress tests using an exercise bike (veloergometry) and a treadmill (treadmill test) are widely used. Such tests with a gradually increasing level of load make it possible to judge the reserve capabilities of heart function.

Using ultrasound echocardiography, it is possible to determine the cause of heart failure, as well as evaluate the pumping function of the myocardium. Using cardiac MRI, coronary heart disease, congenital or acquired heart defects, arterial hypertension and other diseases are successfully diagnosed. X-ray of the lungs and chest organs in heart failure determines congestive processes in the pulmonary circulation, cardiomegaly.

ACUTE HEART FAILURE Diagnosis and treatment at the prehospital stage

What are the main causes of AHF? What is the classification of OSN based on? What is the treatment algorithm at the prehospital stage?

Acute heart failure (AHF), which is a consequence of impaired myocardial contractility and a decrease in systolic and cardiac output, is manifested by extremely severe clinical syndromes: cardiogenic shock, pulmonary edema, acute cor pulmonale.

Main causes and pathogenesis

A decrease in myocardial contractility occurs either as a result of its overload, or due to a decrease in the functioning mass of the myocardium, a decrease in the contractile ability of myocytes, or a decrease in the compliance of chamber walls. These conditions develop in the following cases:

- in case of disturbance of diastolic and/or systolic function of the myocardium during infarction (the most common cause), inflammatory or dystrophic diseases of the myocardium, as well as tachy- and bradyarrhythmias;

- with the sudden occurrence of myocardial overload due to a rapid significant increase in resistance in the outflow tract (in the aorta - hypertensive crisis in patients with compromised myocardium; in the pulmonary artery - thromboembolism of the branches of the pulmonary artery, a prolonged attack of bronchial asthma with the development of acute emphysema, etc.) or due to stress volume (an increase in the mass of circulating blood, for example, with massive fluid infusions - a variant of the hyperkinetic type of hemodynamics);

- in case of acute disturbances of intracardiac hemodynamics due to rupture of the interventricular septum or the development of aortic, mitral or tricuspid insufficiency (septal infarction, infarction or avulsion of the papillary muscle, perforation of the valve leaflets in bacterial endocarditis, rupture of the chordae, trauma);

- with increasing load (physical or psycho-emotional stress, increased inflow in a horizontal position, etc.) on the decompensated myocardium in patients with chronic congestive heart failure.

Classification

Depending on the type of hemodynamics, which ventricle of the heart is affected, as well as on some features of the pathogenesis, the following clinical variants of AHF are distinguished.

- With a congestive type of hemodynamics: • right ventricular (venous congestion in the systemic circulation); • left ventricular (cardiac asthma, pulmonary edema).

- With hypokinetic1 type of hemodynamics (small output syndrome - cardiogenic shock): • arrhythmic shock; • reflex shock; • true shock.

Since myocardial infarction is one of the most common causes of AHF, the table provides a classification of acute heart failure in this disease.

Possible complications

Any of the variants of AHF is a life-threatening condition. Acute congestive right ventricular failure, not accompanied by small output syndrome, in itself is not as dangerous as diseases leading to right ventricular failure.

Clinical picture

- Acute congestive right ventricular failure is manifested by venous congestion in the systemic circulation with increased systemic venous pressure, swelling of the veins (most noticeable in the neck), enlarged liver, and tachycardia. Edema may appear in the lower parts of the body (with prolonged horizontal position - on the back or side). Clinically, it differs from chronic right ventricular failure by intense pain in the liver area, aggravated by palpation. Signs of dilatation and overload of the right heart are determined (expansion of the borders of the heart to the right, systolic murmur over the xiphoid process and protodiastolic gallop rhythm, emphasis of the second tone on the pulmonary artery and corresponding ECG changes). A decrease in left ventricular filling pressure due to right ventricular failure can lead to a drop in left ventricular minute volume and the development of arterial hypotension, up to a picture of cardiogenic shock.

With pericardial tamponade and constrictive pericarditis, the pattern of large circle congestion is not associated with insufficiency of myocardial contractile function, and treatment is aimed at restoring diastolic filling of the heart.

Biventricular failure, a variant where congestive right ventricular failure is combined with left ventricular failure, is not discussed in this section, since the treatment of this condition is not much different from the treatment of severe acute left ventricular failure.

- Acute congestive left ventricular failure clinically manifests itself as paroxysmal shortness of breath, painful suffocation and orthopnea, occurring more often at night; sometimes - Cheyne-Stokes breathing, cough (initially dry, and then with sputum, which does not bring relief), later - foamy sputum, often pink in color, pallor, acrocyanosis, hyperhidrosis and is accompanied by excitement, fear of death. In case of acute congestion, moist rales may not be heard at first, or a meager amount of fine bubbling rales is detected over the lower parts of the lungs; swelling of the mucous membrane of small bronchi can manifest itself as a moderate picture of bronchial obstruction with prolongation of exhalation, dry wheezing and signs of pulmonary emphysema. A differential diagnostic sign that allows one to differentiate this condition from bronchial asthma can be the dissociation between the severity of the patient’s condition and (in the absence of pronounced expiratory dyspnea, as well as “silent zones”) the paucity of the auscultatory picture. Loud, varied moist rales over all the lungs, which can be heard at a distance (bubbling breathing), are characteristic of a detailed picture of alveolar edema. Possible acute expansion of the heart to the left, the appearance of a systolic murmur at the apex of the heart, a proto-diastolic gallop rhythm, as well as an emphasis on the second tone on the pulmonary artery and other signs of load on the right heart, up to the picture of right ventricular failure. Blood pressure can be normal, high or low, tachycardia is typical.

The picture of acute congestion in the pulmonary circulation, which develops with stenosis of the left atrioventricular orifice, essentially represents left atrial failure, but is traditionally considered together with left ventricular failure.

- Cardiogenic shock is a clinical syndrome characterized by arterial hypotension and signs of a sharp deterioration in microcirculation and tissue perfusion, including blood supply to the brain and kidneys (lethargy or agitation, drop in urine output, cold skin covered with sticky sweat, pallor, marbled skin pattern); sinus tachycardia is compensatory in nature.

A decrease in cardiac output with a clinical picture of cardiogenic shock can be observed in a number of pathological conditions not associated with insufficiency of myocardial contractile function - with acute obstruction of the atrioventricular orifice by an atrial myxoma or a spherical thrombus/ball prosthesis thrombus, with pericardial tamponade, with massive pulmonary embolism. These conditions are often combined with the clinical picture of acute right ventricular failure. Pericardial tamponade and atrioventricular orifice obstruction require immediate surgical intervention; drug therapy in these cases can only worsen the situation. In addition, the picture of shock during myocardial infarction is sometimes imitated by dissecting aortic aneurysm; in this case, differential diagnosis is necessary, since this condition requires a fundamentally different therapeutic approach.

There are three main clinical variants of cardiogenic shock:

- arrhythmic shock develops as a result of a drop in cardiac output due to tachycardia/tachyarrhythmia or bradycardia/bradyarrhythmia; after stopping the rhythm disturbance, adequate hemodynamics are quickly restored;

- reflex shock (pain collapse) develops as a reaction to pain and/or sinus bradycardia resulting from a reflex increase in vagal tone and is characterized by a rapid response to therapy, primarily painkillers; observed with relatively small infarct sizes (often in the posterior wall), while there are no signs of congestive heart failure and deterioration of tissue perfusion; pulse pressure usually exceeds a critical level;

- true cardiogenic shock develops when the lesion volume exceeds 40-50% of the myocardial mass (more often with anterolateral and repeated infarctions, in people over 60 years of age, against the background of arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus), is characterized by a detailed picture of shock, resistant to therapy, often combined with congestive left ventricular failure; depending on the selected diagnostic criteria, the mortality rate ranges from 80-100%.

In some cases, especially when it comes to myocardial infarction in patients receiving diuretics, the developing shock is hypovolemic in nature, and adequate hemodynamics are relatively easily restored due to replenishment of the circulating volume.

Diagnostic criteria

One of the most consistent signs of acute heart failure is sinus tachycardia (in the absence of sinus node weakness, complete AV block, or reflex sinus bradycardia); characterized by expansion of the borders of the heart to the left or right and the appearance of a third sound at the apex or above the xiphoid process.

- In acute congestive right ventricular failure, the following are of diagnostic value: swelling of the neck veins and liver;

- Kussmaul's sign (swelling of the jugular veins on inspiration);

- intense pain in the right hypochondrium;

- ECG signs of acute overload of the right ventricle (type SI-QIII, increasing R wave in leads V1,2 and formation of a deep S wave in leads V4-6, depression of STI, II, a VL and elevation of STIII, a VF, as well as in leads V1, 2; possible formation of right bundle branch block, negative T waves in leads III, aVF, V1-4) and signs of right atrium overload (high pointed waves PII, III).

- shortness of breath of varying severity, up to suffocation;

- a drop in systolic blood pressure of less than 90-80 mm Hg. Art. (or 30 mmHg below the “working” level in people with arterial hypertension);

| Figure 1. Algorithm for relieving pulmonary edema at the prehospital stage |

| Figure 2. Algorithm for relieving cardiogenic shock at the prehospital stage |

Treatment of acute heart failure

In any variant of AHF, in the presence of arrhythmias, it is necessary to restore an adequate heart rhythm.

If the cause of AHF is myocardial infarction, then one of the most effective methods of combating decompensation will be the rapid restoration of coronary blood flow through the affected artery, which can be achieved at the prehospital stage using systemic thrombolysis.

Inhalation of humidified oxygen through a nasal catheter at a rate of 6-8 l/min is indicated.

- Treatment of acute congestive right ventricular failure consists of correcting the conditions that caused it - pulmonary embolism, status asthmaticus, etc. This condition does not require independent therapy.

The combination of acute congestive right ventricular and congestive left ventricular failure serves as an indication for therapy in accordance with the principles of treatment of the latter.

When acute congestive right ventricular failure and small output syndrome (cardiogenic shock) are combined, the basis of therapy is inotropic agents from the group of pressor amines.

- Treatment of acute congestive left ventricular failure.

- Treatment of acute congestive heart failure begins with the administration of sublingual nitroglycerin in a dose of 0.5-1 mg (1-2 tablets) and giving the patient an elevated position (in case of an unexpressed picture of congestion - an elevated head end, in case of advanced pulmonary edema - a sitting position with legs down) ; these measures are not performed in cases of severe arterial hypotension.

- A universal pharmacological agent for acute congestive heart failure is furosemide, due to venous vasodilation already 5-15 minutes after administration, causing hemodynamic unloading of the myocardium, which increases over time due to the diuretic effect that develops later. Furosemide is administered intravenously as a bolus and is not diluted; the dose of the drug ranges from 20 mg for minimal signs of congestion to 200 mg for extremely severe pulmonary edema.

- The more pronounced the tachypnea and psychomotor agitation, the more indicated is the addition of a narcotic analgesic to therapy (morphine, which, in addition to venous vasodilation and reducing preload on the myocardium, already 5-10 minutes after administration reduces the work of the respiratory muscles, suppressing the respiratory center, which provides an additional reduction load on the heart. A certain role is also played by its ability to reduce psychomotor agitation and sympathoadrenal activity; the drug is administered intravenously in fractional doses of 2-5 mg (for which 1 ml of a 1% solution is taken, diluted with isotonic sodium chloride solution, bringing the dose to 20 ml and administered 4-10 ml) with repeated administration if necessary after 10-15 minutes Contraindications are respiratory rhythm disturbances (Cheyne-Stokes breathing), depression of the respiratory center, acute obstruction of the respiratory tract, chronic pulmonary heart disease, cerebral edema, poisoning with depressant substances breath.

- Severe congestion in the pulmonary circulation in the absence of arterial hypotension or any degree of acute congestive left ventricular failure during myocardial infarction, as well as pulmonary edema against the background of a hypertensive crisis without cerebral symptoms, are an indication for intravenous drip administration of nitroglycerin or isosorbide dinitrate. The use of nitrate drugs requires careful monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate. Nitroglycerin or isosorbide dinitrate is prescribed at an initial dose of 25 mcg/min, followed by an increase every 3-5 minutes by 10 mcg/min until the desired effect is achieved or side effects appear, in particular a decrease in blood pressure to 90 mm Hg. Art. For intravenous infusion, every 10 mg of the drug is dissolved in 100 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride solution, so one drop of the resulting solution contains 5 mcg of the drug. Contraindications to the use of nitrates are arterial hypotension and hypovolemia, pericardial constriction and cardiac tamponade, pulmonary artery obstruction, and inadequate cerebral perfusion.

- Modern methods of drug treatment have minimized the importance of bloodletting and the application of venous tourniquets to the extremities, however, if adequate drug therapy is impossible, these methods of hemodynamic unloading not only can, but should be used, especially with rapidly progressing pulmonary edema (bloodletting in a volume of 300- 500 ml).

- In case of acute congestive left ventricular failure, combined with cardiogenic shock, or with a decrease in blood pressure during therapy that has not given a positive effect, non-glycoside inotropic agents are additionally prescribed - intravenous drip administration of dobutamine (5-15 mcg/kg/min), dopamine (5- 25 mcg/kg/min), norepinephrine (0.5-16 mcg/min) or a combination thereof.

- A means of combating foaming during pulmonary edema are “defoamers” - substances that ensure the destruction of foam by reducing surface tension. The simplest of these means is alcohol vapor, which is poured into a humidifier, passing oxygen through it, supplied to the patient through a nasal catheter or breathing mask at an initial rate of 2-3 l/min, and after a few minutes - at a rate of 6-8 l/min.

- Persistent signs of pulmonary edema with stabilization of hemodynamics may indicate an increase in membrane permeability, which requires the administration of glucocorticoids to reduce permeability (4-12 mg of dexamethasone).

- In the absence of contraindications, in order to correct microcirculatory disorders, especially with long-term intractable pulmonary edema, the administration of sodium heparin is indicated - 5 thousand IU intravenously as a bolus, then drip at a rate of 800 - 1000 IU/hour.

- Treatment of cardiogenic shock involves increasing cardiac output, which is achieved in a variety of ways, the significance of which varies depending on the clinical type of shock.

- In the absence of signs of congestive heart failure (shortness of breath, moist rales in the posterior lower parts of the lungs), the patient must be placed in a horizontal position.

- Regardless of the clinical picture, it is necessary to provide complete analgesia.

- Stopping rhythm disturbances is the most important measure to normalize cardiac output, even if adequate hemodynamics are not observed after restoration of normosystole. Bradycardia, which may indicate increased vagal tone, requires immediate intravenous administration of 0.3-1 ml of 0.1% atropine solution.

- If the clinical picture of shock is extensive and there are no signs of congestive heart failure, therapy should begin with the administration of plasma expanders in a total dose of up to 400 ml under the control of blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and auscultation of the lungs. If there is an indication that immediately before the onset of acute cardiac damage with the development of shock, there were large losses of fluid and electrolytes (long-term use of large doses of diuretics, uncontrollable vomiting, profuse diarrhea, etc.), then an isotonic solution is used to combat hypovolemia sodium chloride; the drug is administered in an amount of up to 200 ml over 10 minutes, repeated administration is also indicated.

- The combination of cardiogenic shock with congestive heart failure or the lack of effect from the entire complex of therapeutic measures is an indication for the use of inotropic agents from the group of pressor amines, which, in order to avoid local circulatory disorders accompanied by the development of tissue necrosis, should be injected into the central vein: dopamine in a dose of up to 2, 5 mg affects only dopamine receptors of the renal arteries, at a dose of 2.5-5 mcg/kg/min the drug has a vasodilating effect, at a dose of 5-15 mcg/kg/min it has vasodilating and positive inotropic (and chronotropic) effects, and in dose 15-25 mcg/kg/min - positive inotropic (and chronotropic), as well as peripheral vasoconstrictive effects; 400 mg of the drug is dissolved in 400 ml of a 5% glucose solution, while 1 ml of the resulting mixture contains 0.5 mg, and 1 drop - 25 mcg of dopamine. The initial dose is 3-5 mcg/kg/min with a gradual increase in the rate of administration until the effect is achieved, the maximum dose (25 mcg/kg/min, although the literature describes cases where the dose was up to 50 mcg/kg/min) or the development of complications (most often sinus tachycardia exceeding 140 beats per minute, or ventricular arrhythmias). Contraindications to its use are thyrotoxicosis, pheochromocytoma, cardiac arrhythmias, hypersensitivity to disulfide, previous use of MAO inhibitors; if the patient was taking tricyclic antidepressants before prescribing the drug, the dose should be reduced;

- the lack of effect from dopamine or the inability to use it due to tachycardia, arrhythmia or hypersensitivity is an indication for the addition or monotherapy with dobutamine, which, unlike dopamine, has a more pronounced vasodilatory effect and a less pronounced ability to cause an increase in heart rate and arrhythmia. 250 mg of the drug is diluted in 500 ml of a 5% glucose solution (1 ml of the mixture contains 0.5 mg, and 1 drop - 25 mcg of dobutamine); in monotherapy, it is prescribed at a dose of 2.5 mcg/kg/min, increasing every 15-30 minutes by 2.5 mcg/kg/min until an effect, side effect is obtained, or a dose of 15 mcg/kg/min is achieved, and with a combination of dobutamine with dopamine - in maximum tolerated doses; Contraindications to its use are idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis and stenosis of the aortic mouth. Dobutamine is not prescribed for systolic blood pressure <70 mmHg. Art.

- in the absence of effect from the administration of dopamine and/or a decrease in systolic blood pressure to 60 mm Hg. Art. norepinephrine can be used with a gradual increase in dosage (maximum dose - 16 mcg/min). Contraindications to its use are thyrotoxicosis, pheochromocytoma, previous use of MAO inhibitors; If you have previously taken tricyclic antidepressants, the dose should be reduced.

Indications for hospitalization

After relief of hemodynamic disturbances, all patients with acute heart failure are subject to hospitalization in cardiac intensive care units. In the torpid course of AHF, hospitalization is carried out by specialized cardiology or resuscitation teams. Patients with cardiogenic shock should, whenever possible, be hospitalized in hospitals where there is a cardiac surgery department.

A. L. Vertkin, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor V. V. Gorodetsky, Candidate of Medical Sciences O. B. Talibov, Candidate of Medical Sciences

1 The clinical picture of cardiogenic shock can develop with a hypovolemic type of hemodynamics: against the background of active diuretic therapy preceding a heart attack, profuse diarrhea, etc.

How is heart failure treated?

For chronic heart failure, medications (such as ACE inhibitors, beta blockers and diuretics) are used. Medicines are used to prevent complications and improve quality of life. ACE inhibitors and beta blockers can prolong life, but they must be taken regularly to achieve a beneficial effect.

In addition, rhythm therapy (to treat cardiac arrhythmias) and implantation of a three-chamber pacemaker are used. The latter ensures timely activation of the atria and both ventricles. A defibrillator is also often implanted as part of a pacemaker to counteract dangerous heart rhythm disturbances in the setting of severe heart failure. This treatment is also known as resynchronization therapy. An important part of successful treatment is physical therapy.

In the treatment of heart failure, a properly organized diet plays an important role. Dishes should be easily digestible. The diet should include fresh fruits and vegetables as a source of vitamins and microelements. The amount of table salt is limited to 1-2 g per day, and liquid intake to 500-600 ml.

Pharmacotherapy, which includes the following groups of drugs, can improve the quality of life and prolong it:

- cardiac glycosides – enhance the contractile and pumping function of the myocardium, stimulate diuresis, and increase the level of exercise tolerance;

- ACE inhibitors (angiotensin-converting enzyme) and vasodilators - reduce vascular tone, expand the lumen of blood vessels, thereby reducing vascular resistance and increasing cardiac output;

- nitrates - dilate the coronary arteries, increase cardiac output and improve blood filling of the ventricles;

- diuretics – remove excess fluid from the body, thereby reducing swelling;

- β-blockers - increase cardiac output, improve the filling of the heart chambers with blood, reduce the heart rate;

- anticoagulants - reduce the risk of blood clots in blood vessels and, accordingly, thromboembolic complications;

- agents that improve metabolic processes in the heart muscle (potassium supplements, vitamins).

If cardiac asthma or pulmonary edema (acute left ventricular failure) develops, the patient requires emergency hospitalization.

Prescribed drugs that increase cardiac output, diuretics, nitrates. Oxygen therapy is mandatory. Removal of fluid from body cavities (abdominal, pleural, pericardial) is carried out by puncture.

Chronic heart failure: treatment, drugs

CHF is a disease in which patients need to constantly take medications. For chronic heart failure, drugs are used that help slow the progression of the process and improve the patient's condition. In some patients with CHF, treatment requires surgical intervention.

Medicines for chronic deficiency are primary, auxiliary and additional.

The main drugs include ACE inhibitors (angiotensin-converting enzyme), angiotensin receptor antagonists, beta-blockers, aldosterone receptor antagonists, diuretics, ethyl esters of polyunsaturated fatty acids, cardiac glycosides. Cardiac glycoside for the treatment of chronic heart failure is used most often in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Auxiliary drugs for chronic heart failure are used in special clinical situations with complications of CHF. These include nitrates, calcium antagonists, antiarrhythmic drugs, antiplatelet agents, and non-glycoside inotropic stimulants.

Additional medications for chronic insufficiency: statins, indirect anticoagulants.

For patients diagnosed with chronic heart failure, clinical recommendations from doctors relate not only to taking medications, but also to revising their lifestyle in general:

- it is necessary to stop smoking and drinking alcohol;

- bring your weight back to normal;

- follow a salt-free diet. Nutrition for CHF should be balanced, contain a sufficient amount of proteins and vitamins;

- walk more in the fresh air.

Prevention and prognosis

To prevent heart failure, you need proper nutrition, sufficient physical activity, and giving up bad habits. All diseases of the cardiovascular system must be promptly identified and treated.

The prognosis in the absence of treatment for CHF is unfavorable, since most heart diseases lead to its wear and tear and the development of severe complications. When carrying out drug and/or cardiac surgery, the prognosis is favorable, because the progression of the insufficiency slows down or a radical cure for the underlying disease occurs.