The liver, as an important organ, which is entrusted with more than five hundred functions, is very intricately designed by nature. This is an amazing anatomical formation, without which the activity of the human body is impossible, and it constantly surprises researchers by performing completely diverse duties. For this, a specific device was necessary, without which such activity would be impossible, but the more complex any mechanism, the greater the likelihood of its breakdown.

The portal vein of the liver, the norm of which allows you to safely transport the blood flow necessary for full life and oxygen supply, in a pathological state can lead to circulatory disorders of the vital organ and malfunctions of other important segments of the circulatory system. Therefore, special attention is paid to it when conducting research.

How does blood flow in the liver work?

The portal vein (v. portae) begins with a capillary network of unpaired organs located in the abdominal cavity of mammals:

- intestine (more precisely, the mesentery, from which two branches of the mesenteric veins depart - lower and upper);

- spleen;

- stomach;

- gallbladder.

The allocation of a separate venous system for these organs is due to the absorption processes occurring in them. Substances entering the gastrointestinal tract are broken down into their components (for example, proteins into amino acids). But there are substances that are poorly transformed in the gastrointestinal tract. These are, for example, simple carbohydrates and inorganic chemical compounds. And when proteins are digested, waste products arise - nitrogenous bases. All this is absorbed in the capillary network of the intestines and stomach.

Regarding the spleen, its second name is the red blood cell cemetery. Worn-out red blood cells are broken down in the spleen, releasing toxic bilirubin.

During the experiment on removing the liver from animals, all this led to their rapid death. Dangerous blood must be delivered to the liver bypassing other organs. Therefore, nature has endowed this function with a special venous bed that delivers blood with toxins for neutralization - the portal vein of the liver.

Actually, the portal vein is formed by joining the splenic vein of two rather large mesenteric veins. The superior and inferior mesenteric veins, which collect blood from the intestine and accompany the arteries of the same name, supply the portal vein with blood from the intestine (with the exception of the distal parts of the rectum).

The site of formation of venae portae is most often located between the posterior surface of the head of the pancreas and the parietal layer of the peritoneum. The result is a vessel 2-8 cm long and 1.5-2 cm in diameter. Then it passes through the thickness of the hepatoduodenal ligament until it enters the organ in the same bundle with the hepatic artery.

Before the procedure

Ask questions about your medications

You may need to stop taking certain medications before the procedure. Talk to your healthcare provider about which medications you can stop taking. Below are some common examples.

Blood thinners

If you are taking blood thinners (which affect blood clotting), ask your healthcare provider what is best for you. Doctor contact information is listed at the end of this material. Whether your doctor recommends stopping this medication depends on the type of procedure and the reason you are taking the anticoagulant.

Do not stop taking your blood thinner medications without talking to your healthcare provider.

| Examples of blood thinning medications: | |||

| apixaban (Eliquis®); | dalteparin (Fragmin®); | meloxicam (Mobic®); | ticagrelor (Brilinta®); |

| aspirin; | dipyridamole (Persantine®); | nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil®, Motrin®) or naproxen (Aleve®); | tinzaparin (Innohep®); |

| celecoxib (Celebrex®); | edoxaban (Savaysa®); | pentoxifylline (Trental®); | warfarin (Jantoven®, Coumadin®); |

| cilostazol (Pletal®); | enoxaparin (Lovenox®); | prasugrel (Effient®); | |

| clopidogrel (Plavix®); | Fondaparinux (Arixtra®); | rivaroxaban (Xarelto®); | |

| dabigatran (Pradaxa®); | heparin (subcutaneous administration); | sulfasalazine (Azulfidine®, Sulfazine®). | |

Read the resource Common Medicines Containing Aspirin and Other Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) or Vitamin E. It contains important information about the medications you should not take before your procedure and what medications you can substitute for them.

Medicines for diabetes

If you take insulin or other medications for diabetes, ask your healthcare provider who prescribed the medication what to do the morning of your procedure. You may need to change your dose before the procedure. Your healthcare provider will monitor your blood sugar levels during the procedure.

Diuretics (diuretics)

If you are taking any diuretics (which cause you to urinate frequently), ask your healthcare provider what to do next. You may need to stop taking them on the day of your procedure. Diuretic medications are sometimes called diuretics. Examples of such medications include furosemide (Lasix®) and hydrochlorothiazide.

Contrast agent

A contrast agent is a special dye that allows your healthcare provider to see your internal organs better. A contrast agent is injected into the portal vein during your procedure. If you have ever been allergic to contrast dye, tell your healthcare provider.

Removing devices from the skin

If you wear any of the following devices on your skin, the manufacturer recommends removing them before undergoing a scan or procedure:

- Continuous Glucose Meter (CGM)

- Insulin pump

Contact your healthcare provider to schedule an appointment closer to your scheduled device replacement date. Make sure you bring a spare device with you that you can wear after your scan or procedure.

If you are unsure how to monitor your glucose levels when the device is turned off, talk to your diabetes care provider before your visit.

Arrange for someone to take you home

You must have a responsible companion to take you home after the procedure. A responsible companion is someone who can help you get home safely and report problems to your healthcare provider if necessary. Agree on this in advance, before the day of the procedure.

If you are unable to find a responsible escort to take you home, call one of the agencies below. You will be provided with an escort who will take you home. There is usually a fee for these services and you will need to provide transportation. You can take a taxi or rent a car, but you need to have a responsible escort with you.

| Agencies in New York | Agencies in New Jersey |

| Partners in Care: 888-735-8913 | Caring People: 877-227-4649 |

| Caring People: 877-227-4649 |

Let us know if you are sick

If you are sick before your procedure (for example, have a fever, sore throat, cold or flu), call your Interventional Radiology provider. Doctor's working hours: Monday to Friday from 09:00 to 17:00. If you call after 5:00 p.m., or on weekends and holidays, dial 212-639-2000 and ask for the Interventional Radiology specialist on call.

Record your appointment time

Interventional Radiology will call you two business days before your procedure, which is Monday through Friday. If your procedure is scheduled for Monday, you will be called the previous Thursday. If you are not contacted by 12:00 noon on the business day prior to your procedure, please call 646-677-7001.

A staff member will tell you when you should come to the hospital for your procedure. You will also be reminded how to get to the department.

Write down the date, time and location of the procedure in this column.

If for any reason you need to cancel your procedure, please notify the healthcare provider who scheduled it.

to come back to the beginning

Interesting facts about the portal vein

There are some more interesting facts about the portal vein:

- The ligament in which it, together with the hepatic artery, approaches the gate of the liver is in some way not a ligament, but a fold of the omentum. The surgeon can apply pressure with his finger to stop liver bleeding. For a while, of course;

- The portal vein has connections (anastomoses) with almost all veins of the abdominal cavity. Normally, this hepatic portal vein system does not manifest itself in any way. It becomes noticeable in diseases of the organ and conditions leading to portal hypertension. Since the liver cannot hurt, manifestations of increased pressure in the portal vein system may be the first symptoms of a serious pathology (cirrhosis of the liver, thrombosis of the abdominal veins);

- Such a large blood sampling area makes the portal vein the largest vein in the abdominal cavity;

- The portal vein system, together with the liver, is the largest blood depot in the body. Minute blood flow at rest is 1500 ml;

- If we remember where the portal vein is formed, it becomes clear why a tumor of the head of the pancreas manifests itself as portal hypertension. Yandex

Manifestations of portal hypertension can be very different - spider veins on the anterior wall of the abdomen, varicose veins of the esophagus, often discovered by chance. Even hemorrhoids can (rarely) be a manifestation of a local increase in pressure in the portal vein system.

Interrelation and mutual influence

The pathological condition of the liver is one of the main, but not the only reason that the portal vein loses its usual normal state and ability to perform its functions. There are four types of possible pathologies, but each of them may have a variable path to development, not always directly related to the condition of the unpaired organ, but invariably leading to its deterioration in the process of progression.

Portal vein thrombosis

It may occur against the background of injury to the walls due to mechanical damage or be a consequence of iatrogenic complications. Often, thrombosis is the result of an infection from the abdominal cavity or genitourinary system. The cause of thrombus formation is heart failure or dysfunction of the hematopoietic organs, coagulation system, changes in the composition of the humoral fluid. But with the same probability, the cause of vein blockage is obstruction to blood flow - a significant enlargement of the uterus during multiple pregnancies, postpartum complications, a pancreatic tumor.

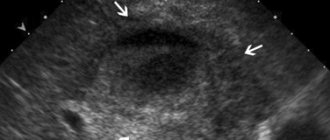

A thrombus can form in the splenic vein and, under the pressure of humoral fluid, migrate into the vein, develop directly in the trunk, or pass from the liver. Acute thrombosis in most cases carries a negative prognosis, but is rare. Death occurs due to the death of unpaired organs after the portal vein is blocked by a thrombus. In chronic cases, only periodic partial closure of the lumen is observed, however, ultrasound is prescribed for characteristic symptoms - unexpected pain in the abdominal region, ascites, swelling of the extremities, hematemesis, rectal bleeding. The stage of the disease is determined by the location of the negative formation; at the third stage, all veins of the abdominal cavity are affected, and at the fourth stage, the blood flow practically stops.

Portal thrombosis can be a consequence of cirrhosis at a certain stage of the disease, acute appendicitis. Often its cause cannot be determined, and it is considered idiopathic. A significant deviation from the norm is observed - the diameter of the PV increases, all the vessels of the vasculature dilate, and cavernous degeneration appears.

Portal hypertension

Unlike thrombosis, it has a direct relationship with liver pathologies (hereditary structural anomalies resulting from unfavorable conditions during gestation or inherent at the genetic level). Such a diagnosis can be made in the absence of a portal vein or its irregular structure, when an artery and vein are combined.

Thrombosis, severe systemic diseases, and neoplasms can cause prehepatic portal hypertension. Infections or biliary cirrhosis, non-infectious inflammation, parasitic invasion are the causes of intrahepatic PG, and only post-hepatic PG is the result of circulatory pathologies - heart disease or blockage of the inferior vena cava.

With total, the entire vascular network is affected, while segmental affects only the splenic vein. The progression of the disease leads to splenomegaly, bleeding from the veins of the gastrointestinal tract, cavernous transformation is also likely, since this is the only way for the body to somehow compensate for the created circulatory deficiency.

Cavernomas PV

In some sources it is identified as a separate pathology, and this is correct, because cavernoma can be a consequence of congenital pathologies, a developmental defect. There are many reasons for this formation, and each case in childhood requires separate consideration. In adulthood, its appearance is associated with chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and in some cases with chronic thrombosis.

Pylephlebitis

Purulent inflammatory lesion of the portal vein, which is asymptomatic, leads to liver damage and death. Until recently, such a diagnosis was within the competence of a pathologist, however, modern research methods make it possible to identify it much earlier and even provide timely assistance.

Material and methods

Computer modeling of medical images obtained from the results of multislice computed tomography (MSCT) was performed on 100 patients. Criteria for inclusion of subjects in the study: age of the subjects from 20 to 90 years inclusive; absence of CT signs of pathology of the upper abdominal cavity; absence of CT signs of portal hypertension and portal vein thrombosis; high quality CT images for constructing a three-dimensional model of blood vessels. Objects that did not meet the specified criteria were not included in the study.

All patients participating in the study underwent CT scanning in a standard position to examine the abdominal cavity. The study protocol at the first stage included a preliminary native examination of the abdominal organs to clarify the scanning area and assess the condition of the abdominal organs and retroperitoneal space. The second stage involved intravenous bolus administration of an isosmolar contrast agent (Omnipaque-350). The purpose of bolus contrast enhancement is to differentiate contrast phases. Arterial, venous and parenchymal phases are distinguished. On average, the arterial phase, in which the filling of the arteries is visualized, begins 20-30 s after the start of contrast agent administration. After 40-60 s, the venous phase begins, during which contrasting of the veins is visualized. The volume of contrast agent administered was from 100 to 150 ml, the injection rate was 3-5 ml/s, and the average radiation dose was 11.3 mSv. Such a study makes it possible to study the anatomical relationships of organs at the slice level with high accuracy intravitally, study the variant anatomy of the vascular bed, and visualize branches with a diameter of less than 1 mm.

The result of the study (tomographic images) is a set of two-dimensional transverse images (English slice), each of which contains a matrix of intensity values in a black and white image. Tomographic images are saved as a DICOM file. DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) is an industry standard for creating, storing, transmitting and visualizing medical images and documents of examined patients.

Of the 100 patients included in the study, there were 56 men and 44 women. The average age of men included in the study was 53±15.21 years, women - 53.9±14.14 years. All patients included in the study were divided into 4 age groups in accordance with the WHO age classification: 1st - young age (from 20 to 44 years); 2nd - middle age (45-59 years); 3 - old age (60-74 years); 4th - senile age (75-90 years).

The 1st group included 31 people (17 men and 14 women, average age 34.7±6.5 years), the 2nd group included 29 people (17 men and 12 women, average age 54.8±3 .9 years), in the 3rd group - 35 people (19 men and 16 women, average age - 64.8±3 years), in the 4th group - 5 people (3 men and 2 women, average age - 81 .8±5.9 years). The distribution of patients in groups is presented in Table. 1 .

Table 1. Distribution of patients by age groups

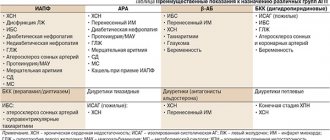

To classify the area of portal vein confluence, classification P was used. Krumm et al. [6] (Fig. 1) , according to which 10 types of confluence are distinguished:

Type A - NBV flows into NE.

Type B - The IMV is located at the angle of the confluence of the SMV and SV, this confluence forms the portal vein.

Type C - The NBV flows into the SMV.

Type D - The accessory mesenteric vein enters the confluence angle as in type B.

Type E - similar to type A with two equal trunks of the NBV and the accessory mesenteric vein, the SBV flows into the SV. Type F - similar to type E, the IMV flows into the accessory mesenteric vein, which in turn is equal in diameter to the SMV and flows into the angle of the confluence of the SMV and SV.

Type G - similar to type A, but the accessory mesenteric vein and the SV enter the SV at the same point.

Type H - no NBV.

Type I - similar to type A - the SBV drains into the SV, but there is an accessory mesenteric vein between the SBV and SMV.

Type J - The NBV is equal in diameter to the SBV and flows into the corner of the merging of the NBV and SV.

Rice. 1. Types of crow vein confluence according to P. Krumm et al. [6]. PV - portal vein, SMV - superior mesenteric vein, IMV - inferior mesenteric vein, SV - splenic vein, AccMV - accessory mesenteric vein.

To study the size of the angles formed at the junction of the roots of the portal vein, we used both a standard study after intravenous contrast and post-processed images with multiplanar reformation in MIP mode and three-dimensional reconstructions.

Virtual morphometry in the Luch-S and Autoplan programs was carried out using a 3D protractor tool.

Measurements were carried out in three planes (sagittal, coronal and axial). The following parameters were recorded: the angle formed by the portal and SMV; the angle formed by the portal and splenic veins; the angle formed by the splenic and SMV; angles of entry of the NBV into the SMV and splenic vein.

After the procedure

After the procedure, your healthcare provider will take you to the recovery room. You may experience bleeding, but this is rare.

While you are in the hospital, tell your healthcare provider if you feel pain. You will be given medicine.

If you go home that day, your nurse will remove your IV catheter. Before you go home, your nurse will give you and your caregiver instructions on how to care for you after you leave.

If you stay in the hospital overnight, you will be moved to a hospital ward. Most people are discharged the day after the procedure.

to come back to the beginning

results

Based on the classification of P. Krumm et al. [6], without taking into account the gender of the patients, it was revealed that the “classic” type of confluence, in which the NBV flows into the SV (confluence type A; Fig. 2, a ), occurred in 37 patients. In 36 patients, the NBV flows into the angle of the confluence of the SMV and SV (type B confluence; Fig. 2, b ). In 16 observations, the NBV flowed into the SMV (type C confluence; Fig. 2, c ). These three options are the most common and together were found in 89 observations. The accessory mesenteric vein was identified in 6 cases. Thus, in 3 patients, type D confluence was detected, in which the accessory mesenteric vein, together with the IMV, entered the angle of the confluence of the SMV and SV. In 2 patients, the IMV and accessory mesenteric vein have equal diameters, with the IMV flowing into the SV as in type A confluence, and the accessory vein flowing into the angle of the confluence of the SMV and SV (type E confluence). In 1 patient, the accessory mesenteric vein and the INV flow into the SV at the same point (type G confluence). In 5 patients there is no NBV (type H confluence). Not a single case of type F, I, or J confluences was identified.

Rice. 2. Variants of portal vein confluence according to P. Krumm et al. [6] (2011). a — confluence of the NBV into the NE (type A);

b — the confluence of the NBV into the corner of the confluence of the SBV and SV (type B); c — confluence of the NBV into the SMV (type C). INV - inferior mesenteric vein; SMV—superior mesenteric vein; SV - splenic vein. In the 56 men who took part in the study, the predominant variant of type A confluence, in which the NBV flows into the SV. 24 men with type A confluence were identified. This is 42.9% of observations among all men. Confluence of the NBV into the angle of confluence of the SMV and SV (type B confluence) was observed in 17 men. This is 30.4% of observations. In 10 men (17.9% of cases), type C confluence was detected, in which the NBV flows into the SMV. In total, confluence of types A, B and C was detected in 91.2% of all observations in men. The accessory mesenteric vein was identified in men in 2 (3.6% of cases) cases. In one case, the accessory mesenteric vein flowed together with the IMV into the angle of the confluence of the IMV and SV (confluence type D). In the second case, the accessory vein drained into the angle of the confluence of the SMV and SV, and the IMV drained into the SV (type E confluence). In 3 (5.2% of cases) cases there was no NBV (type H confluence). Portal vein confluences of types F, G, I and J were not observed in men.

In 44 women who took part in the study, the predominant confluence of the IMV into the angle of the junction of the IMV and SV (confluence type B). This type of confluence in women was observed in 19 (43.1%) cases. In 13 (29.5%) cases, the NBV flowed into the SV (type A confluence). Confluence of the NBV into the SMV (confluence type C) was detected in 6 (13.6%) cases. In total, the first 3 types of portal vein confluence were identified in 87.3% of all observations in women.

The accessory mesenteric vein in women was identified in 4 (9.2%) cases. In two cases, the accessory mesenteric vein flowed together with the IMV into the angle of the confluence of the SMV and SV (type D). In one case, a type E confluence was detected, in which the accessory vein flowed into the angle of the confluence of the SMV and SV, and the SBV into the SV. The entry of the accessory mesenteric vein and the INV into the SV at one point (type G confluence) was observed in one case. The absence of NBV (type H) in women was noted in 2 (4.6%) cases.

Portal vein confluences of types F, I and J were not observed in women (Fig. 3) .

Rice.

3. Variants of portal vein confluence according to R. Krumm et al. [6] (2011) taking into account the gender of patients. The size of the angle formed by the SMV and the portal vein, without taking into account both age and gender, ranged from 100 to 151°. On average, this indicator was 124.11±11.24°. The size of the angle formed by the SV and the portal vein, without taking into account gender and age, ranged from 87.4 to 146° and averaged 119.19±11.73°. The range of fluctuations in the size of the angle of merger of the SV and the SMV is determined by the interval from 91 to 150°. The average size of this angle was 114.62±11.48°. In 37 patients with type A portal vein confluence, the angle at which the INV entered the SV was determined: the minimum size was 52.4°, the maximum was 89.7°, i.e. The NBV flowed into the NE at almost a right angle. The average angle of entry of the NBV into the NE was 76.35±9.17°. In addition, the angle at which the IMB entered the SMV was measured in 16 patients with type C confluence. This angle ranged from 43.1 to 85.1° and averaged 68.7 ± 14.09°.

Significant variability in the angles formed by the roots and trunk of the portal vein made it possible to identify groups of their extreme variants. The range of fluctuations in the average values (M±σ) of the angle formed by the SMV and the portal vein was from 112.87 to 135.35°. 71% of observations fell within this range. In 29% of observations, the angle had parameters both less than the average and greater than the average. The dimensions of the angle formed by the SMV and the portal vein, which were smaller and larger than the average value, were divided into two variant subgroups: small dimensions of the angle (M – 2σ > X > M – σ) and extremely small dimensions of the angle (X< M – 2σ) , as well as angles with large (M + σ < X < M + 2σ) and extremely large sizes (X > M + 2σ). For the angle formed by the SMV and the portal vein, small and extremely small sizes occurred in 14 and 1%, and large and extremely large sizes - in 11 and 3%, respectively. The dimensions of the angle formed by the portal vein and SV, which ranged from 107.46 to 130.92°, i.e. with the average value (M ± σ), are 71%. Small (M – 2σ > X > M – σ) and extremely small (X< M – 2σ) angle sizes occurred in 4 and 8% of cases, respectively. At the same time, large (M + σ < X < M + 2σ) and extremely large (X > M + 2σ) sizes of the angle formed by the portal vein and SV were found in 15 and 3% of cases, respectively. The average value (M ± σ) of the angle between the SMV and SV corresponded to 67% of observations. Small (M – 2σ > X > M – σ) and extremely small (X< M – 2σ) sizes of the angle between the SMV and SV corresponded to 18 and 1% of measurements, respectively. Large (M + σ < X < M + 2σ) and extremely large (X > M + 2σ) angle values corresponded to 13 and 1% of measurements. The average size (M ± σ) of the angle of entry of the NBV into the NE corresponded to 26 (70.2%) measurements. Small (M – 2σ > X > M – σ) and extremely small (X < M – 2σ) sizes were found in 8.2 and 5.4% of measurements. In absolute terms, these are 3 and 2 dimensions, respectively. Large (M + σ < X < M + 2σ) values corresponded to 6 (16.2%) measurements. The study did not reveal extremely large (X > M + 2σ) sizes of the angle of confluence of the NBV into the NE. The average value (M ± σ) corresponded to 10 (62.5%) measurements of the angle of entry of the NBV into the SBV. Extremely small (X < M – 2σ) and extremely large (X > M + 2σ) values of the angle of entry of the NBW into the SBW were not identified in the study; small (M – 2σ > X > M – σ) and large (M + σ < X < M + 2σ) measurement values corresponded to 25 and 12.5%. In absolute values, these are 4 and 2 dimensions, respectively (Fig. 4) .

Rice.

4. Options for the size of the angles of the confluence of the roots and the trunk of the portal vein. Taking into account gender differences, the maximum angle of fusion of the SMV and portal vein in men was 151°, the minimum angle was 103°. The average size of this angle was 123.83±9.43°. In observations in women, the size of the angle formed by the SMV and the portal vein ranged from 100 to 148°. The average size of this angle was 124.45±13.33°. The maximum angle of the fusion of the SV and portal vein in men was 146°, and the minimum was 87.4°. In women, the maximum angle formed by the SV and the portal vein was 144°, the minimum angle was 93.8°. The average size of the angle formed by the SV and the portal vein was 121.05±12.3° in men and 116.83±13.33° in women. The angle formed by the fusion of the SMV and SV ranged from 91 to 138° in men and from 98° to 150° in women. The average angle between the SMV and SV was 112.91±12.01 and 116.79±10.36° in men and women, respectively. In men, the average angle of fusion of the NBV with the SV was 79.3±9.23° and ranged from 52.4 to 89.7°. In women, the NBV flowed into the NE with a minimum angle of 61.3° and a maximum angle of 87.5°. The average size of this angle was 76.43±9.05°. In men, the sizes of the angle of merging of the NBV and SV ranged from 46 to 85.1°, in women - in the range from 43.1 to 80.1°. The average angle was 74.11±10.91° in men and 59.7±14.18° in women. There were no statistically significant differences in the size of the angles formed by the roots and trunk of the portal vein in men and women (Table 2) .

Table 2. Variability of portal vein confluence angles depending on the gender of patients

In young patients, the angle between the SMV and the portal veins ranged from 105 to 145°, and the average value was 125.9±10.98°. In young men, the average angle between the portal vein and the NBV was 125.76±7.47° and ranged from 110 to 140°. In women of the 1st age group, the minimum angle formed by the NBV and portal veins was 105°, and the maximum was 145°. The average value was higher than that of men - 126±14.11°. The average angle between the SV and the portal vein in the study group was 119.08±10.34°, the maximum angle was 139°, and the minimum was 97.6°. In men of the 1st age group, the angle between the SV and the portal vein was greater than in women - 121.03±10.97°. In women, the indicated angle was 116.71±8.96°. At the same time, the range of angle sizes in men was higher and ranged from 97.7 to 139°, in women - from 99° to 132°. The angle between the SV and SMV veins, without regard to gender, in the 1st age group ranged from 93.5° to 128°. The average size of the uga without taking into account gender was 112.68±9.44°. In the described group, the angle of entry of the NBV into the SV was measured in 11 patients. The minimum size of this angle was 59.1°, the maximum was 88°, and the average was 73.79±7.33°. In young women, the NBV flowed into the NE in one case and the angle of entry was 72.4°. In men, the indicated angle ranged from 59.1 to 80.1° and averaged 73.93±7.68°. The IMV flowed into the SMV in young women in one observation and the angle of entry was 80.1°. In young men, the angle of confluence of the NBV into the SMV ranged from 76.8 to 80.1° and averaged 78.45±1.65°. Without taking into account gender in the 1st age group, the angle of confluence of the NBV into the SMV was 79±1.55° and ranged from 76.8 to 80.1°.

In middle-aged men, the mean angle between the SMV and the portal vein in the study was 122.94 ± 9.03° and ranged from 113° to 151°. In women of the 2nd age group, the angle formed by the SMV and the portal vein ranged from 104 to 148°, the average angle was 124.83±11.97°. Generally speaking, in the 2nd age group, without taking into account the gender of the patients, the indicated angle ranged from 104 to 151° and averaged 123.72±10.39°. The maximum size of the angle between the SV and the portal vein in the group of middle-aged patients, regardless of gender, was 139°, the minimum size was 87.4°, the average size was 115.42±12.38°. In men of the described age group, the angle formed by the portal vein and the SV ranged from 87.4 to 139° and averaged 116.58±13.09°. In middle-aged women, the maximum angle between the portal vein and the SV was 93.8°, the minimum was 129°, and the average was 112.81±10.97°.

The angle between the SV and SMV, without taking into account gender, in the group of middle-aged patients ranged from 97 to 150°. The average angle was 117.45±12.02°. In men, the angle formed by the SV and SMV ranged from 97 to 138° and averaged 116.62±11.32°. In women, the range of angle sizes was 99.1-150°, the average size was 119.34±12.89°. In middle-aged patients, the confluence of the NBV into the SV (type A confluence according to P. Krumm et al [6].) was observed in 10 cases. The minimum size of the angle of fusion of the NBV and SV was 62.7°, the maximum was 89.7°, and the average was 73.79±7.33. In women, this angle ranged from 62.7 to 86.8° and averaged 73.67±9.08°. In men of the 2nd age group, the minimum angle of confluence of the NBV into the NE was 65.1°, the maximum - 89.7°. The average size of this angle in men reached 81.28±7.84°. Confluence type C (confluence of the NBV into the SMV) in the 2nd age group was observed in 6 cases. The indicated angle in the minimum dimension was 46°, in the maximum – 85.1°, the average value was 63.75±13.92°. In women in the studied age group, the angle of entry of the NBV into the SMV ranged from 46.8 to 63.7° and averaged 55.2±8.5°. In men of the 2nd age group, the angle of entry of the NBV into the SMV ranged from 46 to 85.1° and averaged 68.02±14.14°.

In the group of elderly patients, without regard to gender, the average angle between the SMV and the portal vein was 124.08±11.47° and ranged from 100 to 148°. The maximum size of the angle between the SV and the portal vein in the specified group of patients, without taking into account gender, was 94°, the minimum was 146°, the average value was 121.94±12.09°. The angle between SV and SMV in the 3rd age group ranged from 91 to 132°. The average angle excluding gender was 112.68±19.94°. In men in the 3rd age group, the average angle formed by the SMV and portal vein was 124.1±10.19° and ranged from 109° to 145°. In women, the same angle in the maximum dimension was 148°, in the minimum - 100°, the average angle was 124.1±10.19°.

When measuring the angle formed by the portal vein and SV in elderly men, its average value was 123.84±12.78° with a range from 94 to 146°. In women of this age group, this angle averaged 119.68±10.79° with a range from 102 to 144°. The angle of fusion of the SMV and SV in elderly men ranged from 91 to 132° and averaged 110.1±13.35°. In women, the indicated angle averaged 115.75±9.11°, the range was from 98 to 132°.

The confluence of the NBV into the SV in the 3rd age group was measured in 14 cases and amounted to 75.48±9.85° with a range from 52.4 to 87.5°. The confluence of the NBV into the SMV was observed in the described group in 7 cases, and the size of the angle formed by them ranged from 43.1 to 84°, the average being 68.54±14.83°. In men, the size of the angle of entry of the NBV into the upper SV was in the range from 52.4 to 86.9°, in women - in the range from 61.3 to 87.5°, the average size of the angle was 74.28 ± 10.41 and 76 .68±9.1°, respectively.

The angle of entry of the NBV into the SMV in men ranged from 68.3 to 84° and averaged 78.02±5.87°. In women, similar measurements ranged from 41.3 to 74.9°, the average value was 55.9 ± 13.7°.

In the group of elderly patients, the angle between the SMV and the portal vein ranged from 103 to 132°, the average value was 115.4±11.63°. In men of the 4th age group, the indicated angle was 116.33±11.95° with a range from 103 to 132°. In women, this angle ranged from 103 to 125° with an average value of 114 ± 11°. Without taking into account gender, in elderly patients, the angle formed by the SV and the portal vein ranged from 113 to 127° with an average value of 122.6 ± 5.27°.

Taking into account gender differences in the group of elderly patients, in men the sizes of the angle between the SV and the portal vein ranged from 121 to 127° with an average value of 125±2.82°. In women, measurements of the indicated angle ranged from 113 to 125°, the average value was 119 ± 6°.

The angle of fusion of the SMV and SV in elderly patients without regard to gender was 123.8±8.13° and ranged from 109 to 130°. In women of this age group, the size of the angle of fusion of the SMV and SV ranged from 121 to 130°, the average value was 125.5±4.5°. The angle of fusion of the SMV and SV in elderly men ranged from 109 to 130° and averaged 122.66±9.67°. The angle of entry of the NBV into the SV in the described group ranged from 71.3 to 85.6°, the average was 80.92±5.82°. In men, the angle of entry of the NBV into the NE ranged from 71.3 to 85.5°, in women - from 81.3 to 85.6°, the average values were 77.4 ± 7.1 and 83.45 ± 2.15 ° accordingly. In the 4th age group, confluence type C (confluence of the NBV into the SMV) was absent (Table 3) .

Table 3. Variability of portal vein confluence angles depending on the age and gender of patients.

There were no statistically significant differences in the sizes of portal vein confluence angles in patients of different age groups (p>0.05).

Day of the procedure

Instructions for drinking before your procedure

You can drink no more than 12 ounces (350 ml) of water between midnight and 2 hours before you arrive at the hospital. Don't drink anything else. Do not drink any liquids two hours before you are scheduled to arrive at the hospital. This also applies to water.

What you need to remember

- Take the medications you were told to take the morning of your procedure. Wash them down with a few small sips of water.

- Do not apply cream or Vaseline® to your skin. You can use deodorants or light lotions to moisturize your skin.

- Don't wear makeup on your eyes.

- Remove all jewelry, including body piercings.

- Leave all valuables, such as credit cards and jewelry, at home.

- If you wear contact lenses, wear glasses instead if possible. If you don't have glasses, bring a contact lens case with you to the hospital.

What to take with you

- List of medications you take.

- Medicines taken for breathing problems (such as inhalers), medicines for chest pain, or both.

- Case for glasses or container for contact lenses.

- A health care proxy form, if you have completed one.

- If you use a CPAP or biphasic positive airway pressure (BiPAP) machine to sleep at night, take it with you if possible. If you are unable to bring your own machine, we will provide you with an identical machine to use during your hospital stay.

to come back to the beginning

Introduction

Many works are devoted to liver resection, both in Russian and foreign literature [1, 2]. At the dawn of the development of surgical hepatology, methods of atypical resections performed without strict consideration of the intraorgan architecture of blood vessels and bile ducts were described. The liver was divided into lobes according to the location of the grooves and the place of fixation of the ligamentous apparatus, as was described by ancient anatomists. Since the middle of the last century, works have appeared on the study of the segmental structure of the liver. A significant contribution to the study of intrahepatic angioarchitecture was made by C. Couinaud; he was based on the anatomy of the portal vein (PV) [3]. Over time, anatomical resection ceased to be an exclusive operation and, with the increasing radicalism of surgical treatment of liver tumors, became increasingly widespread among surgeons. Over the past 15-20 years, the possibilities of surgical treatment have expanded significantly. This is due not only to the introduction of new surgical technologies and improvement of anesthesia, but also to a thorough study of the structural features of the intrahepatic vascular bed and the physiology of the organ [4-6]. In the preoperative period, the key stage for understanding the structure of the vascular structure of the liver and the topical localization of the focal lesion is diagnosis using modern ultrasound and radiation methods [7]. The portal veins are visualized and the hemodynamic characteristics of the portal blood flow are obtained using Doppler ultrasound. The use of modern high-resolution multislice computed tomographs, which allow three-dimensional reconstruction of the object under study, has led to a significant improvement in the visualization of the vascular anatomy of the liver [8].

Despite the large number of works on anatomy, we consider it necessary to pay attention to a number of important, from a surgical point of view, issues of the structure and individual variability of intrahepatic angioarchitecture. As studies show [9–11], the greatest variability in structure is observed in the right branch of the PV; accordingly, the greatest technical difficulties are encountered during operations on the right lobe of the liver. Information on the anatomy and technique of liver resections is the result of a generalization of literature data and our experience. We studied the intrahepatic angioarchitecture of the right lobe of the liver on sectional material by making X-ray angiograms, corrosion preparations, and also compared and interpreted the results with clinical data obtained from the analysis of X-ray and computer portograms.

Thus, the relevance of the problem lies in the need to further improve the technique of liver resection, which requires not only improved knowledge in the field of individual topographic and anatomical features of the liver vascular system, but also the use of modern surgical technologies. This will make it possible to carry out surgical interventions on liver tissue as safely as possible by reducing trauma and increasing the radicalism of the surgical procedure.

The purpose of the study was to study the features of the surgical anatomy of the intrahepatic portal bed of the right lobe of the liver in the context of surgical intervention.