Symptoms of vasospasm of cerebral vessels

Previously, the disease occurred only in elderly patients. In recent years, pathology has become “younger”. It is facilitated by the unfavorable environmental component that prevails in large cities and industrial zones, and the presence of toxic elements in the air. The latter penetrate the respiratory system and are transported directly to the brain, having a negative effect on the blood vessels.

Angiospasm is a fairly powerful and long-term compression of blood vessels. Spasm occurs due to incorrect blood circulation and supply of nutrients. This disease requires immediate treatment, since untimely assistance contributes to the development of complications, such as stroke.

You should consult a doctor if you have the following symptoms:

- Painful sensations in the occipital and temporal region;

- Frequent dizziness;

- High pressure;

- Tinnitus that occurs when a person is in a calm or active state;

- Loss of coordination, speech impairment.

Signs of retinal vasospasm

If the blood vessels of the retina contract sharply, the patient complains of the appearance of “floaters” in front of the eyes, as well as temporary blurred vision and loss of clarity of visual perception. Usually such phenomena last for several minutes.

When an ophthalmologist manages to conduct an ophthalmoscopic examination during such an acute spasm, he can observe such characteristic signs as significant vasoconstriction, as well as blanching of the optic nerve head and other areas of the fundus. When the attack stops, the picture returns to normal.

Spastic narrowing of the arteries with simultaneous dilation of the veins is characteristic of the initial stage of hypertension. The arteries in this case have a tortuous appearance and different thicknesses of the vessel in different areas.

At the second stage of arterial hypertension, these symptoms worsen, while persistent spasm of the arteries leads to their sclerosis, and then to complete obliteration (clogging). Arteriovenous crossovers are noted when a pathologically altered artery presses on a vein. Blood in the fundus of the eye stagnates, blood clots occur, and hemorrhages are possible.

At the terminal stage of the disease, neuro- and angioretinopathy develops. Retinal hemorrhages and swelling are noted. Specific small lesions occur around the macula. Perception loses its sharpness, the sensitivity of the affected eye to light decreases, and the field of vision changes.

Causes of cerebral vasospasm

In addition to stress and unfavorable ecology, other factors also influence the disease, for example, insomnia and chronic fatigue, overstrain of the nervous system, strong emotions, and lack of headwear during the cold season.

Vascular angiospasm can cause the following pathologies:

- Osteochondrosis;

- Aneurysm;

- Damage to the structure of the arteries;

- Diseases of the cardiovascular system;

- Improper functioning of the endocrine system;

- High pressure;

- Oncology.

Diagnostic methods

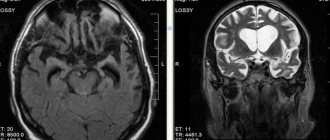

To most accurately identify abnormalities in the activity of cerebral vessels, a specialist will carry out diagnostic procedures:

- duplex scanning of brachycephalic and intracranial arteries - allows for a comprehensive examination of the structure of the vessels, the speed of blood flow in them, as well as the presence of atherosclerotic and thrombotic deposits;

- MRI - the most accurate diagnosis;

- radiography with contrast if it is not possible to perform an MRI.

The full amount of information obtained after the above diagnostic procedures allows the specialist to make an adequate diagnosis.

Angiospasm of leg vessels

Angiospasm can be observed in all kinds of vascular regions and is accompanied by damage to blood vessels and the nervous system. People who are addicted to smoking are most often susceptible to vasospasm in the legs. The disease also occurs as a result of frostbite and hypothermia. The disease is diagnosed based on the dynamics of symptoms, including changes in skin color and a decrease in its temperature.

How the destructive process is formed

As a result of deviations in the transport of electrolytes in the intracerebral vessels, a change in the alternation of time allocated to the phases of contraction of the muscular membrane with the phase of its relaxation is formed.

The result is a significant increase in the duration and force of compression of the arterioles - cerebral ischemia. Local blood flow in the brain structures either slows down significantly and the tissues do not receive enough nutrients and oxygen, or stops altogether - if the lumen of the vessel is completely blocked, for example, in response to a rupture of a cerebral aneurysm.

In such a situation, it is not recommended to delay consultations with specialized specialists and prescribing treatment measures.

Treatment

Mostly conservative methods are used as therapy, which involve strengthening blood vessels and the state of health in general. For the treatment result to be effective, it should begin with a consultation with a doctor, who will collect anamnesis, prescribe additional studies and select the correct treatment method.

Depending on the symptoms, rubbing of the limbs, surgery, novocaine blockade and appropriate medications are prescribed, and a number of other measures are taken to alleviate the patient’s condition.

Features of the clinical picture

The severity of the symptoms of cerebral vasospasm will directly depend on the diameter of the affected vessels, their location and the duration of ischemia itself.

The main sign of pathological narrowing of cerebral vessels is intense headache - starting in one area of the brain, it often spreads over large areas. It can manifest itself in the form of heaviness, a feeling of being squeezed by a hoop in the head.

Additional symptoms that indicate cerebral vasospasm:

- possible irradiation of pain impulses to the neck, forehead, eyes;

- repeated increase in discomfort if the victim lies on his stomach;

- intense dizziness, nausea;

- when coughing and sneezing, symptoms worsen;

- deterioration of memory parameters;

- excessively rapid fatigue;

- decreased performance;

- flashing of flies, zigzags before the eyes;

- the presence of increased sweating;

- less often – pale skin discoloration, changes in pulse parameters;

- numbness and tingling in the temple area.

In some cases, the above symptoms preceded a vascular accident - a stroke or rupture of an aneurysm. Patients complained of acute hearing and vision disorders, difficulty with motor and speech activities.

The condition worsened until loss of consciousness, convulsions, and the presence of various paresis and paralysis.

Diagnostics

Diagnosis of pathology is carried out on the basis of:

- Taking anamnesis. The doctor evaluates the nature of the pain, the time of its occurrence, duration, and the factors that provoked the discomfort. The specialist collects not only personal but also family history.

- Blood and urine tests. Cholesterol and sugar levels must be assessed. Experts also study other important indicators.

- ECG. It is best to conduct an electrocardiographic study during pain.

- Daily Holter monitoring. In this case, the doctor can assess the general condition of the heart muscle and the factors that provoke pain.

- Cold and ergometrine tests. They allow you to provoke a cardiac reaction and evaluate all its features.

- EchoCG. This examination allows you to find problems that contribute to heart failure. Also during the diagnosis, the doctor evaluates the functionality of the ventricles, the size of the cavities and other parameters.

- Coronary angiography. This examination is aimed at determining coronary artery stenosis.

- Load test. During this examination, ischemia can be detected.

PsyAndNeuro.ru

Unfortunately, misconceptions about anxiety disorders and their differences from depression lead to misunderstandings about the role of anxiety in coronary heart disease (CHD), although the relationship between anxiety disorders and cardiovascular disease began to be studied more than 100 years ago. It is surprising that, despite the inextricable connection of anxiety with the functions of the cardiovascular system, the etiological and prognostic links between anxiety disorders and coronary artery disease have been addressed only recently, in the last decade.

Recent evidence suggests that anxiety disorders increase the risk of developing CHD; however, the potential mechanisms underlying the putative association of anxiety with cardiovascular health are complex and poorly understood. From a prognosis perspective, in patients with CAD, symptoms of anxiety and anxiety disorders increase the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (eg, myocardial infarction, left ventricular failure, coronary revascularization, stroke), suggesting the importance of anxiety disorders in cardiac practice.

In this review, special attention is paid to panic disorder, since the symptoms of panic disorder largely overlap with the symptoms of coronary artery disease. Other anxiety disorders will be mentioned when their symptoms are relevant to the association of anxiety with CHD.

Anxiety may go undetected or misdiagnosed in a group of patients with known, suspected, or subclinical CAD. Surveys of experts show that doctors lack knowledge about panic disorder and its treatment. Clinicians are not well informed about the characteristics of panic disorder and its distinctive diagnostic features: recurrent and unexpected panic attacks accompanied by persistent worry or worry in anticipation of further panic attacks or their consequences, and maladaptive behavior, including avoidance behavior.

The clinical nuance is that many symptoms characteristic of a panic attack overlap with the clinical picture of coronary artery disease, as well as arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy, which makes differential diagnosis difficult. For example, chest pain and shortness of breath are panic symptoms but are also typical of myocardial infarction and angina.

The coincidence of subjective cardiorespiratory symptoms in anxiety and in cardiovascular diseases only complicates the understanding of the complex relationship between anxiety and coronary artery disease. Additionally, people with panic disorder may experience physical symptoms of undiagnosed medical conditions such as coronary spasm, microvascular angina, and slow coronary blood flow, in addition to CAD, defined as ⋝50% coronary artery stenosis.

Thus, it is likely that panic disorder is sometimes a misdiagnosis. Therefore, some authors caution that many cases of panic disorder may be misdiagnosed arrhythmias, and panic symptoms may subside once the arrhythmia is controlled. Other experts, on the contrary, believe that in the presence of cardiorespiratory symptoms that cannot be explained by diseases of the cardiovascular system, panic disorder or hypochondria can be assumed.

A diagnosis of an anxiety disorder does not exclude cardiovascular disease, and the presence of high anxiety does not indicate the absence of coronary artery disease. Concerns about the heart and its function are often observed before coronary catheterization and coronary revascularization. Ideally, confirmation of an anxiety disorder diagnosis should be made by an experienced mental health professional.

The main psychiatric diagnostic systems, DSM and ICD, stipulate that a diagnosis of panic disorder cannot be made if panic symptoms appear as a direct result of diseases such as coronary artery disease. According to this principle, a more appropriate diagnosis would be “anxiety related to physical illness.” This distinction is important for diagnostic nomenclature, but not for anxiety treatment, which is independent of the diagnosis of CAD.

With regard to anxiety detection, due to differences in clinical training, studies quantifying the prevalence of panic disorders in patients with CAD are heterogeneous. Non-psychiatrists estimate the prevalence of panic disorder to be lower compared to specialists with psychiatric training. The prevalence of panic disorder in studies that were not blinded for the presence of coronary artery disease was estimated to be lower than in studies that were blinded. Because the authors of the published studies did not assess general health status, it is unclear whether physicians tend to attribute physical symptoms to the presence of CAD.

Anxiety, as a rule, is not associated with the severity of IHD, and in this sense, anxiety is perhaps similar to subjective pain, the severity of which cannot reliably judge the degree of physical injury. The lack of association between anxiety and the severity of CAD may be explained by the fact that panic disorder is characterized by anxiety sensitivity, usually defined as fear of sensations and symptoms associated with arousal of the autonomic nervous system. As a consequence, cardiorespiratory symptoms are typically exacerbated by cognitive and behavioral processes, including hypervigilance, hypervigilance, catastrophizing, and avoidance, which lead to lower thresholds for somatic awareness.

There is a fairly strong relationship between anxiety and subjective assessment of CAD symptoms, such as chest pain and shortness of breath. Not surprisingly, patients with anxiety are more likely to perceive physical symptoms as serious and are more likely to end up in emergency departments not with a heart attack but with a panic attack or non-cardiac chest pain.

On the other hand, there is evidence that anxious patients end up in the emergency department with myocardial infarction more often than patients with myocardial infarction but without anxiety.

| Symptoms of a panic attack | Similar symptoms of ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy |

| Rapid heartbeat, irregular heartbeat | Irregular heartbeat, arrhythmias (eg, ventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation) |

| Sweating | Cold sweat |

| Feeling of lack of air, suffocation | Dyspnea, orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion, wheezing |

| Feeling of tightness in the throat | Pain, feeling of heaviness, constriction, tightness in the jaw and neck |

| Chest pain or discomfort | Angina, chest pain |

| Nausea or abdominal discomfort | Nausea |

| Dizziness, unsteadiness, lightheadedness, weakness | Dizziness, feeling of lightheadedness |

| Chills or fever | Cold sweat |

| Fear of death | Fear of death |

In the group of patients with confirmed coronary artery disease, the prevalence of anxiety disorders is 10-23%. The most common types of anxiety disorders in CHD are panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Other common anxiety disorders include agoraphobia, which is often comorbid with panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobias, and anxiety-related disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Prevalence of anxiety in IHD and in the general population [1]

| Disorder | Prevalence in patients with CAD (%) | Prevalence in the general population (%) |

| GTR | 7,97 | 3,1 |

| Panic disorder | 6,81 | 2,7 |

| Agoraphobia | 3,62 | 0,8 |

| Social phobia | 4,62 | 6,8 |

| Specific phobias | 4,31 | 8,7 |

| OCD | 1,8 | 1 |

| PTSD | 12 | 3,5 |

Etiological and prognostic studies have demonstrated a connection between GAD, panic disorder, PTSD and cardiovascular diseases. The presence of etiological and prognostic associations is noteworthy because most studies tend to emphasize the role of depression in CAD, but 50% of patients with CAD and a depressive disorder also have an anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorders are highly comorbid with depressive disorders and this comorbidity significantly complicates treatment, so if one disorder is present, evaluation for the presence of the other disorder should be performed.

The existence of etiological connections between anxiety and IHD began to be discussed more than 100 years ago, but comprehensive research on this topic began only recently. Several large and well-powered longitudinal case-control studies have demonstrated that anxiety is associated with coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death.

Retrospective studies show that increased anxiety during the 24-hour period before a heart attack increases the risk of heart attack by 2-9 times the effect on heart attack risk that anxiety episodes experienced at other times have. This may be explained by the fact that episodes of acute and excessive anxiety affect the state of plaques in the coronary vessels, as a result of which they are destroyed and coronary occlusion develops; however, due to the retrospective nature of the studies, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Panic disorder increases the likelihood of developing coronary heart disease, severe adverse cardiovascular events, and heart attack. The risk remains significant after adjusting for depression. A parallel study of depression and anxiety disorders is important because the etiological risk of CHD is influenced differently by individual disorders and comorbidities. In particular, panic disorder without comorbid depression is associated with cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease. Stratification of anxiety disorders according to the presence of comorbid depression suggests that anxiety increases the risk of CHD as well as depression. Authors of several studies caution that reverse causation cannot be ruled out for etiological associations because most cohort studies did not perform coronary angiography at baseline. For this reason, subclinical CAD could be misdiagnosed as panic attacks.

Anxiety symptoms are associated with relatively poor treatment outcome or recurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease or heart attack. Analysis of anxiety disorder subtypes revealed different associations with CHD. GAD is primarily associated with poor treatment outcomes. This conclusion about the role of GAD may be explained by the lack of prognostic research on other anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder and PTSD.

There remains some uncertainty regarding whether anxiety disorders contribute to the poor prognosis of CAD. The American Heart Association and the German Heart Association recommend that researchers focus their efforts on identifying the independent effects of anxiety disorders and their subtypes on cardiovascular prognosis.

Several studies have confirmed the prognostic importance of GAD for recurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events. The presence of GAD approximately doubles the risk of severe adverse cardiovascular events. GAD is associated with an increased risk of poor outcomes from arterial bypass grafting.

Prognostic studies regarding anxiety symptoms also support an increased risk of recurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality. However, not all studies confirm a positive association between anxiety and severe adverse cardiovascular events. Some studies have found a reduced risk, suggesting a protective effect of anxiety. These results appear to be a statistical artifact of multicollinearity between anxiety and depression rather than evidence that anxiety improves cardiovascular prognosis.

The biobehavioral mechanisms linking panic and CAD are complex, bidirectional, and poorly understood. Biological risk factors mediating the relationship between anxiety and microvascular damage, such as slow coronary blood flow, microvascular angina, and arterial stiffness, are poorly documented.

Panic disorder may be associated with preexisting cardiometabolic risk factors, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, kidney disease, and diabetes, so studying the relationship between anxiety and CHD will likely address what CHD and other chronic diseases have in common.

Regarding the behavioral mechanisms that are responsible for the development of atherosclerosis, cross-sectional studies involving patients with anxiety disorders show the predominance of such a behavioral risk factor as tobacco smoking. A strong comorbid association of anxiety disorders with alcoholism and substance abuse has been documented. The strong association between anxiety disorders and alcohol abuse implies a common etiology, common risk factors, or defective coping strategies.

Paradoxically, concerns about your health do not necessarily prompt lifestyle changes in terms of physical activity and diet. Psychometric indicators indicating increased anxiety about health are recorded simultaneously with indicators indicating an increased risk of developing coronary artery disease.

Another behavioral risk factor directly associated with CAD is cardiorespiratory fitness. Several longitudinal studies have shown that poor cardiorespiratory fitness is a predictor of depressive disorders in old age. It can be assumed that there is a similar relationship with anxiety disorders, as patients with panic disorder with high levels of somatic anxiety are almost three times more likely to report low levels of physical activity compared to people with low somatic anxiety.

The association of cardiorespiratory fitness and physical activity with anxiety disorders is more complex than that with depression. There is increasing recognition that exercise avoidance behavior is common among patients with anxiety disorders, especially those suffering from panic attacks. Exercise avoidance is associated with anxiety sensitivity and fear of somatic sensations, such as those caused by aerobic exercise.

This is supported by cardiopulmonary stress testing studies in which patients with panic disorder tend to refuse to continue testing at the same maximum oxygen uptake levels at which other subjects do not stop testing.

Avoidance of exercise and fear of physical sensations have clear consequences for patients with coronary artery disease undergoing cardiac rehabilitation. Persistent anxiety and somatization are strong predictors of decreased physical performance after cardiac rehabilitation.

Experiments aimed at inducing and quantifying the physiological symptoms of panic disorder use carbon dioxide inhalation (inhalation of a mixture of oxygen with 35% CO2). This can cause shortness of breath, dizziness and mild anxiety in most participants, and panic attacks in those who have or are at risk of panic disorder. During the experiment, subjective assessment of the strength of panic symptoms and anxiety was higher in the group of people with panic disorder than in control groups.

In a 2005 study [2], in 81% of patients with coronary artery disease with comorbid panic disorder, a carbon dioxide inhalation test induced myocardial ischemia. A 2014 study [3] used single-photon emission computed tomography to evaluate reversible panic-induced myocardial ischemia. In addition, heart rate, blood pressure and 12-lead ECG were measured. Only 10% of patients experienced myocardial ischemia in a panic state.

Because of this large difference in results, it remains unclear whether panic attacks lead to reversible myocardial ischemia. It is important to note that the ischemic consequences of induced panic in patients with high-risk CAD with comorbid panic disorder have not been documented.

Other studies of the cardiovascular response to panic have focused on the sympathetic nervous system as a mediator between the heart and brain. Increased sympathetic discharges during panic attacks are associated with changes in the QRS complex, in particular the QT interval. There is a link between decreased heart rate variability and anxiety disorders. A 2014 meta-analysis found that anxiety disorders are associated with significant reductions in HRV measured by time domain as well as frequency domain methods.

Other proposed mechanisms by which panic and anxiety contribute to the development of atherosclerosis and recurrence of severe adverse cardiovascular events include the increased inflammatory response noted in people with anxiety disorders, including patients with comorbid coronary artery disease. The most data has been collected on increased levels of C-reactive protein, which indicates an increased risk of developing coronary artery disease. It is also known that in anxiety disorders the levels of interleukins, tumor necrosis factor and adrenomedullin increase. Increased migration of anti-inflammatory immune cells may lead to increased platelet aggregation and instability of coronary plaques.

Treatment of panic disorder in patients with CAD has been largely ignored in the scientific literature, to the detriment of our understanding of anxiety disorders in CAD. Most of the evidence for treatment effectiveness actually comes from studies of depression in which reduction in anxiety was only a secondary outcome, or from studies using only self-reported anxiety.

A 2014 systematic review found that no controlled trials specifically targeted anxiety disorders in patients with CAD. This issue remains a blank spot in the literature and clinical practice.

The complex nature of panic disorder accompanying coronary artery disease requires adaptation of standard cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) methods. Treatment of panic disorder concomitant with ischemic heart disease or cardiomyopathy is complicated by the following points:

(a) diagnostic overlap between symptoms experienced in anxiety and heart disease;

(b) high risk associated with ignoring chest pain and delaying contacting a doctor in case of a possible myocardial infarction;

(c) CBT, based on the idea of catastrophic distortion of bodily symptoms, must be modified to take into account real cardiovascular risk;

(d) experiments with induction of symptoms (eg, through hyperventilation) may be dangerous due to the risk of myocardial ischemia.

Transdiagnostic CBT and metacognitive therapy that target cognitive and behavioral processes common to anxiety and depression may be useful in treating anxiety.

Reviews of the current scientific literature show that when treating anxiety and depression in patients with coronary artery disease, effect sizes are lower than in groups of patients with other chronic diseases, such as diabetes. Large-scale studies in cardiology (ENRICHD, SADHART, CREATE) have demonstrated the complexity of treating depression and anxiety in coronary artery disease.

However, most studies have focused on the results of the same type of intervention - either the use of only psychotropic drugs, or only psychotherapy. Medical interventions, including CBT and psychotropic medications, have a small but significant effect on the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.

Regarding psychotropic medications, the European Society of Cardiology EUROASPIRE IV study showed that in a group of patients hospitalized for coronary artery disease, anxiolytic medications were prescribed to only 2.4% of patients at hospital discharge and 2.7% of patients at follow-up. This estimate is consistent with other studies using systematic screening for depression and anxiety in cardiology, which show that psychotropic medications are still used significantly more often than CBT or other types of psychotherapy. It is unclear whether this is due to patient preference, clinician preference, or lack of resources to provide CBT.

Interestingly, the use of benzodiazepines after myocardial infarction is associated with a reduced risk of recurrent infarction. This relationship has a J-shaped curve in the graph, indicating the benefit of low to medium doses of benzodiazepines compared to high doses. Anxiolytic drugs with a sedative effect, such as benzodiazepines, should be used cautiously. They are generally not used in CBT. Regardless of the risk of addiction, the rationale for avoiding these medications in CBT is that taking anxiolytics can become part of a safety behavior strategy or a maladaptive coping strategy, and thereby interfere with healing by prolonging anxiety and increasing the need for medications during a panic attack or before situations causing anxiety.

Thus, CBT is generally considered the preferred treatment strategy for anxiety, with more reliable and durable treatment results in the long term without relapse [4]. For this reason, the use of benzodiazepines in the treatment of patients with coronary artery disease is usually limited, and serotonergic drugs are first-line drugs.

The effectiveness of serotonergic drugs, including SSRIs and SSRIs, in the treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with coronary artery disease was confirmed by the SADHART and CREATE studies. The risk of mortality is not reduced by taking SSRIs, but the risk of readmission is reduced (although there are reviews that suggest that taking SSRIs does not reduce the risk of readmission).

Possible pleiotropic effects of serotonergic drugs include a decrease in platelet aggregation ability and an improvement in endothelial function. Potential side effects include an increased risk of bleeding, as well as the ability of escitalopram to prolong the QTc interval, and therefore should not be prescribed at doses above 40 mg/day.

In addition to CBT and serotonergic medications, some experts suggest the use of supervised aerobic exercise as a treatment for CAD panic by providing experiential and interoceptive experience of somatic sensations such as shortness of breath, palpitations, and sweating. Aerobic exercises, as part of cardiac rehabilitation, provoke somatic symptoms in a safe and controlled environment. In patients with panic disorder, such exercise (for example, several 25-minute sessions on a treadmill) improves maximum oxygen uptake. It is also known that regular physical activity can have a positive effect on anxiety disorder symptoms. However, because people with anxiety and depression are less likely to participate in cardiac rehabilitation, studies showing the benefits of exercise for anxiety may only involve those who do not avoid exercise.

Author of the translation: Filippov D.S.

Source : Tully PJ, Cosh S., Pedersen S. (2020) Cardiovascular Manifestations of Panic and Anxiety. In: Govoni S, Politi P, Vanoli E (eds) Brain and Heart Dynamics. Springer, Cham.

Bibliography:

[1] Tully PJ, Cosh SM, Baumeister H. The anxious heart in whose mind? A systematic review and metaregression of factors associated with anxiety disorder diagnosis, treatment and morbidity risk in coronary heart disease. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(6):439–48

[2] Fleet R, Lesperance F, Arsenault A, Gregoire J, Lavoie K, Laurin C, et al. Myocardial perfusion study of panic attacks in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(8):1064–8

[3] Fleet R, Foldes-Busque G, Grégoire J, Harel F, Laurin C, Burelle D, et al. A study of myocardial perfusion in patients with panic disorder and low risk coronary artery disease after 35% CO 2 challenge. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(1):41–5.

[4] Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A, Middleton H, Anastasiades P, Gelder M. A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(6):759–69

Consequences of cerebral vasospasm and its prevention

If you do not seek medical help in a timely manner, a negative condition can cause quite serious consequences:

- severe cerebral ischemia – high risk of heart attacks and strokes;

- delayed intellectual development in children;

- complete blindness and deafness in adult patients;

- aneurysm rupture;

- various paresis and paralysis;

- persistent attacks of severe migraine.

To avoid the above consequences, experts recommend adhering to the following rules:

- diet correction - avoidance of fatty, heavy, fried foods;

- get rid of existing bad habits;

- avoid chronic stressful situations;

- visit fitness centers and gyms more often;

- eliminate somatic pathologies in a timely manner.

Treatment of cerebral vasospasm, as well as its prevention, is impossible without the desire for a healthy lifestyle - eat right, avoid physical inactivity, get proper rest at night, and adjust your work and rest schedule.

Causes of vasospastic angina

The exact reasons for the development of pathology have not yet been studied.

It is assumed that it is caused by increased sensitivity of coronary vascular cells to various active substances. An attack of vasospastic angina can also be triggered by dysfunction of the internal walls of the arteries. Another cause of pathology is spasm of the coronary arteries. The main risk factors include:

- smoking;

- hypothermia;

- violation of the composition of electrolytes;

- autoimmune diseases.

Pathology can also be caused by a decrease in blood supply to the heart. In this case, the number of heart contractions decreases, the myocardium becomes electrically unstable, which leads to rhythm disturbances. Vasospastic angina can also be caused by stenosing coronary atherosclerosis, which occurs due to problems with the arteries.

Providing quick help to yourself

A full treatment course should only be prescribed by a neurologist. If there is a deterioration in health caused specifically by cerebral vasospasm, the following measures can be taken at home:

- wash with cool distilled water;

- lie down in a darkened room, place an orthopedic pillow under your head;

- drink 25-30 drops of valerian;

- if there are no contraindications, take an analgesic or antispasmodic tablet;

- conduct a self-massage session;

- Drink slowly in small sips of warmed water with a drop of honey.

If you cannot cope with the attack on your own, then it is not recommended to delay consultation with a specialist.

Symptoms

With angiospastic syndrome, prolonged spasm of the vessels of the extremities occurs. Such patients react acutely to cold air. There is a feeling of coldness in the upper and lower extremities, the color of the skin changes, and numbness is felt. Spasm of the blood vessels in the hand leads to tremor. People with angiospastic syndrome take longer to warm up. Sometimes, with prolonged exposure to low temperatures, atrophic processes develop.

Obliterating atherosclerosis occurs due to thickening of the walls of blood vessels due to fat deposition. Atherosclerotic plaques form, narrowing of the lumen of blood vessels occurs, up to their blocking in certain areas. This does not allow blood to enter the tissues, they do not receive the necessary nutrients.

Symptoms of arterial insufficiency:

- pain in the legs that occurs when walking, which goes away after rest;

- the pain has a constraining, squeezing character;

- limitation of leg mobility;

- thickening of nails;

- hair loss or slow hair growth;

- feeling of coldness, tingling, numbness in the legs;

- ulcerative lesions on the skin;

- lameness.

With spasm of the blood vessels in the legs, the pain is localized in the lower part of the limbs, in the calves. When large blood vessels are blocked, discomfort occurs in the thighs and buttocks. It becomes difficult for patients to walk, run, or climb stairs. With atherosclerosis in the later stages, even painkillers do not help patients cope with pain.

With obliterating endarteritis, damage to small vessels occurs. This occurs due to autoimmune processes and leads to the proliferation of connective tissue. The disease develops quickly. The main symptoms of vascular spasm in the legs during endarteritis:

- leg fatigue;

- lameness;

- sensation of burning and coldness in the fingers of the lower extremities;

- increased sensitivity, pallor or cyanosis of the skin;

- convulsions;

- deterioration of hair and nail growth;

- ulcerative lesions.

With the onset of obliterating endarteritis, patients notice an increase in symptoms after walking a distance of about 200 meters. Over time, this figure decreases; it is difficult for a person to walk more than 60 meters.

If you have diabetes, there is a risk of vascular damage to the upper and lower extremities (microangiopathy). As a result, ischemia occurs, that is, oxygen starvation of tissues.