Kinds

In medicine, there are various classifications of coronary pulmonary fistulas, but in most cases, patients are diagnosed with the following types:

| Name | Description |

| Congenital fistula | The pathological condition is diagnosed in 98-99% of cases in patients with other heart defects. |

| Acquired | The main reason is surgical intervention in the area of the heart muscle or coronary vessels. |

In 50% of cases, patients are diagnosed with a right-sided coronary pulmonary fistula. In 30% of cases, the left coronary artery is affected. In 4% of cases it is a bilateral fistula, and 7% is a single pathological fistula.

The severity of the disease also depends on the type of fistula drainage. Taking these data into account, coronary pulmonary fistula provides the following classification:

| Name | Description |

| Arteriovenous anastomosis | Coronary pathology is diagnosed in patients in 90% of cases. A congenital anomaly that occurs as a result of communication between the coronary artery and the right heart, coronary sinus, or pulmonary trunk. |

| Arterio-arterial fistula | The pathological condition is diagnosed in 10% of cases. The outlet is located between the blood vessels that nourish the myocardial tissue and the left atrium or ventricle. |

Each type or form of the disease is accompanied by characteristic clinical signs that will help the cardiologist make an accurate diagnosis. There are also single or multiple vascular pathologies. Small fistulas do not exceed 2 mm in diameter. In large fistulas, shunts larger than 2 mm are formed.

Russian Scientific Society of Specialists in X-ray Endovascular Diagnostics and Treatment

Gorbatykh A.V., Krestyaninov O.V., Soynov I.A., Nichay N.R., Voitov A.V., Ivantsov S.M. FSBI "NNIIPC im. acad. E.N. Meshalkin" of the Ministry of Health of Russia

Abstract

Coronary heart fistulas are a rare congenital defect of the coronary circulation. As a rule, the course of the defect is favorable, however, with a large coronary-right atrial fistula, volume overload occurs with progressive heart failure. Traditionally, it is customary to close such fistulas using artificial circulation. We present a case of endovascular closure of a large coronary-right atrial fistula.

Key words: Coronary heart fistula; Congenital heart defect; transcatheter embolization; coronary artery anomaly

Introduction

Coronary heart fistulas are a rare congenital defect of the coronary circulation. The course of coronary-cardiac fistula is in most cases asymptomatic, and the diagnosis, as a rule, is a diagnostic finding when performing echocardiography, angiography, MRI or CT of the heart [1]. However, the development of frequent complications of the coronary blood flow “steal” syndrome, coronary thrombosis and embolism, progressive heart failure, and atrial fibrillation requires early surgical intervention [2]. Currently, this pathology is eliminated using artificial circulation [3]. We present a successful clinical case of endovascular closure of a coronary-right atrial fistula. Clinical case

Boy E., 11 years old, 29 kg, was admitted to the clinic with a diagnosis of coronary atrial fistula with complaints of shortness of breath during exercise and fatigue. According to chest x-ray, LC was 65%. Transthoracic echocardiography showed dilatation of the mouth and trunk of the left coronary artery up to 1 cm, as well as turbulent flow in the right atrium; according to color Doppler ultrasound, the flow size was 4.8 mm, and the estimated pressure in the pulmonary artery was increased to 48 torr. An MSCT study with contrast confirmed a coronary-right atrial fistula. A diffusely dilated vessel, 10.5 x 8.5 mm, originated from the left sinus of Valsalva, which had a U-shaped bend from which the Cx and LAD originated. Retroaortically, between the ascending aorta and the left atrium, the dilated vessel drained into the cavity of the right atrium in the form of two closely spaced trunks with diameters of 7 mm and 6 mm.

For further investigation, the patient was referred for cardiac catheterization. The study was performed on spontaneous breathing, without oxygen. Vascular access was achieved through the right femoral vein and left femoral artery. 4 Fr Terumo diagnostic catheters were used. The coronary-right atrial fistula was contrasted, and a maximum expansion of up to 13 mm was revealed. Selective coronary angiography did not reveal any stenotic pathology of the coronary arteries. The normal anatomy of the venous return to the true coronary sinus, which is located in the right atrium, is determined. Pressure in the PP is 14/8(11) Torr, in the RV 50/3(23) Torr. Blood samples were taken from the chambers of the heart and great vessels for oxygenation - Qp/Qs 1.6. (Fig. 1).

Rice. 1: MSCT of coronary-right atrial fistula: A) three-dimensional reconstruction of CF, cranial projection; B) contrast MSCT, direct projection, relationship between fistula and LCA; C) direct projection, showing the place of drainage of the CF by two separate trunks into the right atrium.

Through the arterial access, a Wishper 0.014″ conductor was passed through the fistula into the right atrium and IVC, the conductor was captured with a lasso trap, the conductor was withdrawn through the venous access, thus forming an arteriovenous loop. Using venous access, a delivery device SFP8 Fr was carried out along the coronary guide, through which the PDA occluder “LifeTech” XJFD 1012 was delivered to the fistula. The occluder is located in the cavity of the fistula, proximal to the division of the fistula into trunks, thus closing the entire lumen of the fistula. Control angiography showed minimal contrast release through the body of the occluder. Pressure in the pancreas is 30/4 torr. There were no complications during the procedure. Surgery time 35 minutes, fluoroscopy 12 minutes. (Fig. 2).

Rice. 2: A) An “arteriovenous loop” is formed to carry out the delivery system via transvenous access; B) the delivery device is installed in the CF; C) control angiography, PDA occluder completely closes the CF cavity.

Pressure bandages were applied to the vascular access sites; after the procedure, the child was taken to the general department; the bandages were removed after 12 hours. Auscultation does not detect a diastolic murmur, and according to echocardiography, no pathological discharge in the RA is detected, the fistula is hermetically closed. After 4 days the child was discharged in satisfactory condition.

6 months after the operation, a control echocardiogram was performed according to which: there were no discharges at the level of the fistula.

Discussion

Coronary-right atrial fistula is a rare congenital pathology, the frequency of which is 0.08-0.1% of all congenital heart defects. The first description of this defect was made by Krause in 1865. The first successful surgical treatment was performed in 1947 by Bjork and Crafoord. The natural course of the defect is usually favorable, however, with a large coronary-right atrial fistula, volume overload occurs with progressive heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. Therefore, a Qp/Qs ratio of more than 1.5, as with any septal defects, is an absolute indication for surgical treatment [4,5]. The patient described in our clinical case had all the signs of volume overload of the right heart (BV 65%, pressure in the RV 50/3(23) torr), the Qp/Qs ratio was 1.6, this was our indication for surgical treatment. Currently, many methods have been proposed for closing coronary fistulas, from the traditional method of open-heart surgery under cardiopulmonary bypass to embolization of small coronary fistulas with adhesive solutions [6]. To determine the choice of surgical correction method, we performed MSCT examination and coronary angiography. MSCT study showed the spatial location of the coronary fistula with the right atrium, and coronary angiography showed the anatomy of the coronary bed. Taking into account all the advantages of endovascular treatment over operations under IR, we performed embolization of a coronary-right atrial fistula with a PDA occluder with good clinical and angiographic results. Having carried out a control echocardiography study after 6 months, we did not find any residual shunts.

Conclusion

Our clinical case shows that with suitable coronary-right atrial fistula anatomy, endovascular embolization is possible and a safe procedure.

- Waynes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM et al. ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the Management of adult with Congenital Heart Disease: report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Forse on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines on the management of adult with congenital heart disease). Circulation. 2008; 118(23):714–833.

- Chirantan V. Mangukia. Coronary artery fistula. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012; 93:2084–92.

- Yorihiko Matsumoto, Takaya Hoashi, Koji Kagisaki, and Hajime Ichikawa. Successful surgical treatment of a gigantic congenital coronary artery fistula immediately after birth. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012 Sep; 15(3): 520–522.

- Wang NK, Hsieh LY, Shen CT, Lin YM. Coronary arteriovenous fistula in pediatric patients: a 17-year institutional experience. J Formos Med Assoc 2002;101:177-82.

- Omelchenko A.Yu., Nichay N.R., Gorbatykh Yu.N. Minimally invasive technologies for closing ventricular septal defects. // Pathology of blood circulation and cardiac surgery. 2015. No. 1. P. 110–118.

- Karagoz T, Celiker A, Cil B, Cekirge S. Transcatheter embolization of a coronary fistula originating from the left anterior descending artery by using n-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2004; 27: 663-5.

Etiology and prevalence

In all patients with congenital heart disease (CHD), coronary pulmonary fistula is diagnosed in 0.2-0.4% of cases. Of these, 0.08-0.18% are adults. A fistula may appear without associated clinical signs. A physical examination helps determine it.

It is impossible to determine the prevalence of coronary fistulas because small fistulas are rarely diagnosed during routine screening or treatment for another condition. Pathological fistulas of small size proceed quietly, without disturbing myocardial circulation.

In this situation, there are no symptoms of cardiac dysfunction. Sometimes a small fistula closes spontaneously, and in some situations it continues to grow and provokes the appearance of characteristic clinical signs.

A large pathological fistula progresses and causes serious complications (myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, rupture of blood vessels, aneurysm and even human death).

SBUG - Anomalous origin of the coronary artery from the pulmonary artery

In modern cardiology, the names of defects are often assigned a shortened name - an abbreviation (and the names of operations are given the names of the doctors who first proposed the technique, for example, the Fontan operation). Typically, these abbreviations are formed from the words in the name of the defect - VSD (ventricular septal defect), PDA (patent ductus arteriosus), etc. The short name of the defect “anomalous origin of the coronary artery from the pulmonary artery” is formed according to a different principle: from the first letters of the names of doctors who Blunt, White, Garland were the first to describe this defect, and the letter “C” at the beginning of the abbreviation means “syndrome”.

In a properly developed heart, both coronary, or coronary, arteries, which carry arterial blood to the heart itself, arise from the beginning of the ascending aorta, at its very root. These are its first, most important branches, thanks to which the heart receives its oxygen and nutrients.

With the SBUG heart defect, which we are now considering, one of the coronary arteries begins not from the aorta, but from the adjacent pulmonary artery, which contains venous rather than arterial blood. Most often this happens with the left, i.e. the main artery that supplies most of the heart muscle.

What happens then?

In intrauterine life, both coronary arteries receive blood under the same pressure, because in the pulmonary artery the pressure is almost equal to the pressure in the systemic circle, and the difference in blood oxygen saturation is insignificant.

But after birth, the conditions of blood flow in the heart change dramatically. The right artery continues to supply arterial blood from the aorta. And the left, and with it the entire mass of the muscles of the left ventricle, receives arterial blood only through small bypass paths, the so-called “collaterals”, from the system of the same right artery. From the left artery, part of the blood flows into the pulmonary artery, without having time to enter the vascular network and release the oxygen contained in it. What happens is what is called the “stealing syndrome.” For the heart muscle, such theft is dangerous: the left sections begin to suffer very quickly from a lack of oxygen and nutrients, and the whole picture is extremely reminiscent of and, in essence, coronary artery disease

, so well known to everyone. SBUG and ischemia, which often develops in older people, have completely different causes. However, the consequences are very similar: heart failure, heart attacks, accompanied by severe pain, about which the infant cannot say anything.

Symptoms most often appear during the first 4 months, and if nothing is done, almost 90% of children with this defect will not live to see their first birthday. In some children, collaterals develop well and children can survive the neonatal period, but, nevertheless, require surgical care.

In any case, as with many other defects, the diagnosis should be known as early as possible. Usually suspicion, and sometimes an absolutely correct diagnosis, is visible on a regular electrocardiogram, the picture of which is quite typical for this defect.

Cardiac catheterization will accurately determine the location of the ostium of the left coronary artery.

There are several methods of surgical correction. First of all, you can simply ligate the ostium of the anomalous left coronary artery. This will stop the leak, increase the pressure in the coronary pool and significantly improve the nutrition of the heart muscle. Today, closure of the orifice can be done without surgery, in the X-ray surgery room. But, even if this is impossible, the ligation operation is quite simple, does not require artificial circulation and can be performed in any pediatric cardiac surgery clinic.

In some cases, it is possible to perform an anastomosis between the subclavian and coronary arteries by ligating its mouth. This is also a closed operation. Both of them are palliative, i.e. do not solve the main problem: restoration of the normal bicoronary blood supply system to the heart.

It is clear that this can only be solved by “transplanting” the mouth of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery to the aorta, where it should come from. There are several surgical options for this, and the details should be explained to you by the surgeon operating on your child.

The operation is not easy, quite lengthy, is performed under conditions of artificial circulation, and, most importantly, it is not frequent, because this defect is quite rare. Therefore, only large centers that have a constant flow of patients with congenital heart defects have significant experience.

How to get treatment at the Scientific Center named after. A.N. Bakuleva?

Online consultations

Stages and degrees

Clinical manifestations of a coronary pulmonary fistula will help determine the degree of development of the shunt, its location and size. Considering the prevalence of the pathological condition, the following forms of coronary pulmonary fistula are distinguished:

| Name | Description |

| Generalized | A rare pathological condition characterized by the formation of multiple fistulas with serious circulatory impairment. |

| Localized | One pathological shunt is formed, which is located between the vein and artery. In most cases it appears with other heart defects. |

In each case, the patient develops characteristic clinical symptoms. The cardiologist selects the treatment method, taking into account the diagnosis and existing pathological changes.

Causes of arteriovenous fistulas

An arteriovenous fistula can occur as a complication of a procedure such as cardiac catheterization. During catheterization, a long, thin tube called a catheter is inserted into an artery or vein in the groin, neck, or arm and passed through the blood vessels to the heart. If the needle used for catheterization crosses an artery and a vein, the preconditions for the formation of an arteriovenous fistula are created, but this complication does not occur often.

Injuries.

It is also possible to form an arteriovenous fistula after a gunshot or knife wound. This occurs when there are injuries in the part of the body where the vein and artery are tightly adjacent to each other.

Congenital arteriovenous fistulas.

Some people have arteriovenous fistulas from birth. Although the cause of congenital arteriovenous fistulas is not completely clear, it is assumed that there is a disruption in the development of arteries and veins in the prenatal period.

Genetic diseases.

Arteriovenous fistulas in the lungs can be caused by an inherited disease (Rendu-Osler-Weber disease) that causes blood vessels to develop abnormally throughout the body, especially in the lungs.

Surgically created arteriovenous fistula.

For patients with end-stage renal disease, an arteriovenous fistula may be surgically created to facilitate dialysis. If a dialysis needle is inserted into a vein too many times, it can become scarred and stop functioning. The creation of an arteriovenous fistula causes the vein to widen by connecting to a nearby artery, which simplifies puncture and allows for a higher blood flow rate. Typically, an AV fistula is formed on the forearm.

Symptoms

The clinical picture of the pathological condition depends on the size of the resulting fistula. If a small hole appears, there are no signs of a coronary pulmonary fistula.

A pronounced clinical picture appears when one of the ventricles is significantly overloaded, against which heart failure often occurs. A child aged 2-3 months is hospitalized with disturbances in the functioning of the cardiovascular system.

In children, coronary pulmonary fistula is characterized by the following symptoms:

- the skin turns pale;

- the baby gets tired quickly during feeding, so he often refuses the breast;

- nervous excitability appears;

- the baby is slowly gaining weight;

- when the child screams, the nasolabial triangle turns blue;

- sweating increases;

- breathing quickens;

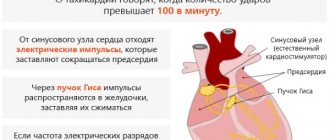

- tachycardia, angina pectoris occurs;

- there is a slowdown in physical development.

Progressive pathological processes provoke symptoms of heart failure. In some situations, patients' legs swell, the liver becomes enlarged, and severe shortness of breath and cough occur. At night, the respiratory process is disrupted and wheezing is heard.

In adult patients, acquired coronary pulmonary fistula is characterized by the following clinical symptoms:

- heart failure progresses;

- severe shortness of breath appears;

- heart rate increases;

- performance decreases;

- the liver enlarges;

- general weakness appears in the body;

- patients complain of swelling of the lower extremities, especially in the evening;

- in some situations, a pain syndrome appears behind the sternum, which radiates to the left shoulder blade and arm.

In young people, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation appears, which is accompanied by disruptions in the functioning of the heart, shortness of breath and chest pain.

Significant overload of the cardiac sections leads to the appearance of pronounced symptoms of chronic circulatory disorders. The end result is the risk of developing acute heart failure.

Many manifestations of coronary pulmonary fistulas occur during physical activity. Pain syndrome appears in the chest area, feels like an angina attack, and is accompanied by fainting. In rare cases, patients are diagnosed with endocarditis.

The symptoms of the disease cannot be ignored, since a pronounced picture indicates the presence of a medium to large coronary pulmonary fistula. Without timely treatment, the risk of a heart attack increases.

Bland-White-Garland syndrome

Anomalies of the coronary arteries are almost terra incognita for modern cardiology, at the same time, according to various sources, they are found in 0.6% - 5.64% of cardiac patients, but there is a possibility that the incidence is much higher. The anatomical variants of the coronary vessels, their pathophysiological and clinical significance, and prognosis have not been sufficiently studied, as a result of which there are no substantiated recommendations for the treatment of patients, and errors in diagnosis and choice of treatment are common.

In the vast majority of cases, anomalies of the coronary arteries are discovered posthumously, not being the cause of death, or accidentally during instrumental examination for another reason, and do not cause pathological conditions during life. Thus, there are prerequisites for determining new “normal” variants of the anatomy of the coronary vessels, as indicated by P. Angelini in his works, proposing to identify coronary vessels by the characteristics of their middle and distal segments or microvascular basin, and not by the place of origin and course of the proximal segments.

The vast majority of anomalies of the coronary arteries are benign, but there is a group of anomalies that are fraught with permanent or periodic disturbances in the blood supply to the myocardium and severe consequences of ischemia without early diagnosis and treatment. Often their only manifestation is sudden cardiac death. This group includes Bland-White-Garland syndrome .

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA - anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery), or Bland-White-Garland syndrome (BWG), is a rare congenital heart defect (1 in 300 thousand newborns) and accounts for 0.25% of all UPS.

SBUG refers to hemodynamically significant (“major”) anomalies of the coronary arteries (CA). In 5% of cases, it is accompanied by other congenital heart diseases: patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular or atrial septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, coarctation of the aorta. Without proper treatment, the prognosis is poor. The average age of onset of life-threatening conditions in SBUG is 33 years, and sudden cardiac death is 31 years. Women get sick more often.

The anatomical description of the defect was first given in 1911 by the Russian pathologist A.I. Abrikosov, who described the autopsy of a 5-month-old child with a left ventricular aneurysm. A comprehensive description of the syndrome was first given by E. Bland, P. White and J. Garland, who worked at the Massachusetts General Hospital, in 1933.

They described the case of a 3-month-old infant with progressive feeding problems, cardiomegaly on chest x-ray, and ECG evidence of left ventricular involvement. At autopsy, it was found that the left coronary artery (LCA) originated from the pulmonary artery (PA). An effective treatment for this pathology was found only in 1960, when Sabiston et al. showed the presence of retrograde blood flow from the LCA to the PA. Ligation of the anomalous LCA at the site of its origin from the PA saved the life of the sick child.

Abnormal origin of the LMCA from the PA occurs in embryogenesis as a result of a violation of the separation of the conotruncus by the septum into the aorta and PA or a combination of persistence of endocardial cushions in the pulmonary artery and their defective involution in the aorta. The genetic background of the disease has not been studied. It is believed that the cause may be mutations in the CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator), MEN1 (multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1) and PKP2 (plakophilin-2) genes.

Clinical picture of SBUG

The spectrum of clinical manifestations of SBUG is diverse. There are infantile and adult types of the disease.

Figure 1 | SBUG classification.

Source: Peña E. et al. ALCAPA syndrome: not just a pediatric disease //Radiographics. – 2009 In the infantile, or lethal, type of SBUG (85–90% of cases), symptoms usually manifest in the second month of life. Newborns appear healthy, since the relatively high resistance of the pulmonary artery still supports anterograde blood flow through the abnormal pulmonary artery, and fetal hemoglobin provides the myocardium with oxygen. At 1–2 months of a child’s life, the resistance of the vascular bed of the lungs decreases due to the closure of the ductus arteriosus, which leads to a decrease in anterograde blood flow and myocardial perfusion.

Classic symptoms (fussiness, crying, colic, shortness of breath, pallor, cyanosis, sweating, regurgitation, feeding difficulties) described by Bland et al. in 1933, allow one to suspect pathology of the coronary arteries. As a rule, anxiety attacks occur after or during feeding or crying, when the myocardial oxygen demand increases, and last several minutes. Between attacks the child appears healthy. Sick children lag behind in physical development.

On examination, expansion of cardiac dullness, cardiac hump, auscultation of normal tones and absence of noise are detected, or the noise of mitral regurgitation, gallop rhythm, occasionally, more often in 2-3 years of life, a soft continuous noise in the upper parts along the left edge of the sternum, reminiscent of the noise in patients with a coronary fistula or patent ductus arteriosus, increased II tone over the PA with the development of pulmonary hypertension, hepatomegaly. Over time, due to insufficient development of collaterals, infarctions of the anterolateral wall of the left ventricle, mitral valve insufficiency and chronic heart failure develop.

In some cases, regurgitation on the MV may mask the manifestations of the underlying defect, which can lead to diagnostic error and inadequate surgical tactics. In the absence of surgical correction, in 90% of cases death occurs within the first year of life.

If the patient has a dominant right type of blood supply to the heart and there is a network of numerous well-developed intervascular anastomoses in the coronary artery system, symptoms may be absent or mild, and the disease progresses to the adult type (10–15% of cases). Some adult patients with SBUG do not experience illness, but much more often the anomaly manifests itself with shortness of breath, palpitations, syncope, angina pectoris, pulmonary hypertension, cardiomyopathy, ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Symptoms are not always associated with physical activity and may occur suddenly at rest; the results of functional tests are often false negative, which makes diagnosis difficult.

Due to the development of a large number of collaterals, blood is shunted from the right coronary artery (RCA) to the LMCA and PA and a steal phenomenon is observed. In some cases, SBUH does not manifest itself until a later age (over 30 years), which is explained by adaptation not only to chronic ischemia of the myocardial area supplied by the LCA, but also to blood shunting. It is assumed that adaptation occurs due to:

- ensuring LV perfusion from the RCA along the collaterals between the RCA and LCA;

- reduction of the myocardial territory dependent on the LCA, as a result of the dominance of the RCA;

- reducing the shunting of blood from the arterial to the venous bed due to the appearance of stenosis of the left artery orifice over time;

- development of collaterals of bronchial arteries, providing perfusion of ischemic myocardium.

However, usually adaptations do not provide sufficient blood supply to the LV and chronic subendocardial myocardial ischemia develops, increasing the risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Sudden cardiac death occurs in 80–90% of cases of SBUG. Initially, it was believed that the cause of sudden cardiac death was hypoplasia of the coronary artery, bending or bending of the proximal ectopic segment of the coronary artery (extending tangentially from the aorta), an acute angle of origin and a slit-like or flap-like shape of the orifice of the coronary artery, the course of the artery between the aorta and the pulmonary artery, which leads to compression ("scissors").

P. Angelini identifies several mechanisms of coronary stenosis:

• Coronary hypoplasia

The intramural invaginated segment of the proximal ectopic artery is smaller in circumference than the more distal extramural vessels. The author proposes the hypoplasia index (the ratio of the circumference lengths of the intramural segment and the more distal one on intravascular ultrasound) as a valuable quantitative parameter. The congenital course of the artery in the aortic media most likely leads to abnormal growth of the coronary artery before and after birth.

• Lateral compression

On cross-section, the intramural segment is ovoid rather than round in shape. Lateral compression reduces the area compared to the cross-sectional area of a round vessel with the same circumference. Lateral compression is characterized by an asymmetry coefficient (the ratio of the smaller diameter to the larger diameter on intravascular ultrasound). During systole, the diameter decreases even more.

Thus, a patient may be suspected of having SBUG if they have unexplained cardiomegaly, mitral regurgitation, or persistent systolic murmur over the cardiac region.

Instrumental diagnostics of SBUG

Figure 2 | Suggested diagnostic protocol for adult patients at risk of developing coronary artery anomalies. Source: Angeline P. Coronary artery anomalies—current clinical issues //Tex Heart Inst J. – 2002

In 80–90% of cases, the diagnosis of SBUG is made at autopsy. Screening diagnostics of coronary artery anomalies is most relevant for athletes and military personnel. According to the American National Registry of Sudden Death in Athletes, coronary artery anomalies are the second most common cause of sudden cardiac death (17%), second only to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. It is reported that functional tests and radionuclide methods often do not detect temporary ischemia in athletes with coronary artery anomalies. Between 55% and 93% of patients who died from sudden cardiac death caused by coronary artery anomalies had no previous cardiac symptoms, and less than 10% of them presented to a cardiologist with symptoms related to the anomaly.

A direct indication of SBUG is the visualization of the LMCA arising from the pulmonary trunk (most often from its left inferolateral part immediately behind the PA valve). Next, the LCA follows the interventricular groove and splits into the left anterior descending and circumflex arteries. Indirect signs of SBUG are coronary tortuosity, dilated RCA, multiple dilated collaterals between the RCA and LMCA, LV hypertrophy and dilatation, myxomatous degeneration and ischemic dysfunction of the papillary muscles, hypokinesis of the LV wall, dilated bronchial arteries.

The diagnostic procedure of choice for diagnosing SBUG is coronary angiography with injection into the aortic root, however, due to the anatomical features of the orifice of the anomalous LMCA, it is not always possible to visualize its course. Aortography is used for radiological diagnostics in children under one year of age, coronary angiography - in children over 5 years of age. The procedure is fraught with complications, which often include temporary ECG changes (11%), temporary bradycardia (2.5%), vascular disorders (11.6%) and serious complications such as ventricular fibrillation (0.6%).

Most diagnoses of SBUG are based on echocardiography with color Doppler mapping. EchoCG allows to avoid complications of coronary angiography and assess MV dysfunction. Additional studies are carried out if it is impossible to establish an accurate diagnosis using echocardiography or for differential diagnosis. Transthoracic echocardiography is used in children due to the presence of a good acoustic window (in adults, transesophageal echocardiography is more sensitive).

Figure 3 | 3-month-old boy with an anomalous origin of the LCA from the pulmonary artery

Transthoracic echocardiography (A, B) shows normal origin of the RCA (arrow in A) and LCA (arrow in B). C. Oblique CT scan of the heart visualizes the normal origin of the RCA (tip), but there is no connection (arrow) between the LCA and the left aortic sinus. D. CT volumetric reconstruction clearly visualizes the anomalous origin of the LMCA (black arrow) from the pulmonary trunk (white arrow). An enlarged left ventricle is visible. Source: Goo HW Coronary artery imaging in children //Korean journal of radiology. – 2015

Cardiac MRI provides additional information about the direction of blood flow in the LCA (cine-MRI with the SSFP sequence), the condition of the valves, myocardium, local contractility, and associated defects, which is important for preoperative assessment and postoperative monitoring of patients. During the study, the patient is not exposed to ionizing radiation, which is important in pediatrics. Cardiac MRI is used to detect subendocardial ischemia and myocardial fibrosis, which may be a substrate for lethal arrhythmias, using late-phase enhanced images after gadolinium injection.

ECG-synchronized MSCT angiography visualizes not only the anomalous LMCA, but also the dilated and tortuous RCA, multiple intercoronary collateral vessels, and dilated bronchial arteries better than MRI.

Radionuclide cardiac imaging methods allow one to assess myocardial perfusion and the functional significance of coronary artery abnormalities. These include thallium stress scintigraphy, single-proton emission computed tomography, and positron emission tomography. Single-proton emission CT (SPECT)-MRI and positron emission tomography (PET)-MRI detect myocardial ischemia in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients. With a hybrid CT-coronary angiography/SPECT-MRI study, it is possible to detect blood flow disturbances in the areas supplied by the coronary artery, even in the absence of perfusion defects. Radionuclide methods generally do not influence the decision about surgical intervention and are not used when examining most patients.

Often the first sign of SBUG is rhythm disturbances, which pose a risk of sudden cardiac death. However, ECG signs of hypertrophy and overload of the left heart are noted in all patients with SBUG. Surface ECG mapping and the 12-channel Holter monitoring method, which helps to identify transient periods of myocardial ischemia, even with negative results of other stress tests, may be promising in the diagnosis of LV myocardial ischemia in this category of patients.

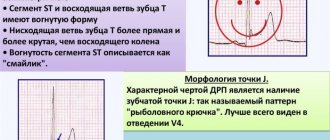

The ECG in infants with LAD usually shows anterolateral LV infarction, evidenced by abnormal Q waves and transient ST interval changes in leads I, aVL, V5, and V6. 20–45% of patients do not have Q wave abnormalities, and abnormal growth of the R wave in the precordial leads may suggest the presence of SBUG.

There are temporary, associated with current damage, and longer-term, associated with the disappearance of muscle tissue, changes in the ECG. The first signs of damage are pointed T waves, indicating local hyperkalemia, which disappear after a few hours and are often undetected. Then successively changes in the ST segment appear, elevation of the J point with a concave ST segment and further elevation of the J point with bulging of the ST segment.

Sometimes there is reciprocal depression of the ST segment in leads II, III, aVF and even V1 and V2. Signs of disappearance of muscle tissue are the appearance of a Q wave and a decrease in the amplitude of the R wave in the affected leads. Over the next two weeks, the ST segment becomes isoelectric, the T wave becomes inverted and symmetrical, the amplitude of the R wave decreases, and the Q wave deepens. The only ECG signs of anterolateral infarction after the end of the acute phase are abnormal Q and R waves.

The above changes are nonspecific and characteristic of acute myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy, however, the simultaneous presence of the following four ECG signs is characteristic only of SBUG and allows for differential diagnosis:

- Q wave above 0.3 mV (3 mm);

- Q wave width is greater than 30 ms;

- qR complex in at least one of leads: I, aVL, V5 and V6. Absence of Q waves in all inferior leads (II, III, aVF).

Figure 4 | ECG of a 72-year-old woman with ALCAPA. Source: Fierens C. et al. A 72 year old woman with ALCAPA //Heart. – 2000. – T. 83. – No. 1. – S. e2-e2

Figure 5 | ECG of a 3-month-old child with ALCAPA. Source: Hoffman JIE Electrocardiogram of anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery in infants //Pediatric cardiology. – 2013

These changes occur in 55–80% of cases of SBUG. The reasons for the absence of abnormal Q waves are not well understood, but in adult patients it is associated more with subendocardial infarction than with transmural infarction; more with the bottom than with the front; more with small-focal than large-focal. It is worth noting new, but not yet widely used, diagnostic methods, for example, intravascular ultrasound and measurement of intracoronary pressure with determination of FFR.

Differential diagnosis of SBUG is carried out with myocarditis, Kawasaki disease, vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa or Takayasu arteritis), scleroderma, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, dilated cardiomyopathy, congenital MV failure, stenosis and coarctation of the aorta.

Treatment of SBUG

Bland-White-Garland syndrome is an absolute indication for surgical treatment.

Survival 20 years after surgery performed in infancy is 95%. The sparse data on surgical treatment of adult patients with sudden cardiac death also look promising, but there are still no randomized controlled trials to evaluate the long-term results of different types of correction of the defect.

In 1960, Sabiston et al., of Johns Hopkins Hospital, described the treatment of a 2.5-month-old child with SBUG. The child had difficulty feeding, shortness of breath, and grunting sounds. Chest X-ray revealed cardiomegaly, and ECG showed evidence of recent myocardial injury. Cardiac catheterization revealed LV dilatation and dysfunction; an abnormal LMCA was not visualized. After a complete examination, a decision was made to undergo surgical intervention for LV revascularization. During the operation, myocardial infarction and an anomalous LCA were discovered.

In order to determine the direction of blood flow along an abnormal coronary artery, Sabiston et al. measured systolic pressure in the PA and LCA, which was 25 and 30 mm Hg. respectively. When an anomalous vessel was occluded at its origin from the pulmonary artery, the pressure in it increased to 75 mm Hg, ensuring retrograde blood flow through the collaterals. Oxygen saturation in the LCA was 100%, in the PA - 76%, which also indicated the presence of blood flow through the collaterals. Sabiston et al. recommended ligation of an abnormal LCA as an effective method of treating pathology.

In recent decades, several methods of surgical treatment of SBUG have been proposed. The simple application of a ligature to an anomalous artery at the point of its origin from the PA, described by Sabiston et al., while effective, turned out to be fraught with serious early and late complications due to the fact that after the application of a ligature, the coronary blood supply to the heart is provided only by the RCA and is entirely dependent on the degree of development of collaterals . In 1966, Cooley et al. reported a method for creating a bicoronary myocardial blood supply system. By creating a communication between the aorta and the LCA using a Dacron prosthesis, they restored direct anterograde blood flow into the LCA. In subsequent years, other methods of creating a double-coronary system were proposed - bypass surgery with the saphenous vein, internal mammary artery, and left subclavian artery.

Proven complications of the listed methods of surgical correction are recanalization of the anomalous coronary artery, an increased risk of atherosclerosis, and severe ischemic mitral regurgitation. More modern methods do not carry such risks.

The modern method of surgical correction of SBUG is based on that proposed in 1974 by Neches et al. direct implantation of LCA into the aorta. The orifice of the anomalous LCA is isolated from the PA along with a small flap of the PA and connected to the aortic root to form a bicoronary system. The described method is a selection operation for SBUG. Postoperative mortality ranges from 0–16% depending on the degree of preoperative myocardial damage. The main complication may be severe blood loss due to rupture of the anomalous artery during transplantation. In adults, direct implantation of the LMCA is often impossible due to tissue rigidity and the large distance from the LMCA orifice to the aorta. In these cases, it is preferable to bypass the anomalous LMCA using an arterial and venous graft. However, the risk of stenosis of the transplanted vessel is higher when using a vein graft. The saphenous vein graft maintains patency by an average of 80% for 5–8 years.

If there are contraindications to direct implantation of the LCA into the aorta, the Takeuchi procedure has been used since 1979. It consists of creating a tunnel inside the PA (aortopulmonary window), through which the aorta communicates with the mouth of the anomalous LMCA. This method is associated with a high incidence of supravalvular pulmonary artery stenosis and tunnel obstruction.

In patients with irreversible myocardial damage, despite correction with the formation of a double-coronary system, heart transplantation is indicated. In patients at high risk of ventricular fibrillation (patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and low ejection fraction), an implantable cardioverter defibrillator may be used.

Sources:

- Yamanaka O., Hobbs RE Coronary artery anomalies in 126,595 patients undergoing coronary arteriography //Catheterization and cardiovascular diagnosis. – 1990. – T. 21. – No. 1. – pp. 28-40.

- Angelini P. Coronary artery anomalies: an entity in search of an identity //Circulation. – 2007. – T. 115. – No. 10. – pp. 1296-1305.

- Angelini P. Coronary artery anomalies—current clinical issues //Tex Heart Inst J. – 2002. – T. 29. – P. 271-278.

- Clinical recommendations for the management of children with congenital heart defects / Ed. Boqueria L.A. - M.: NTsSSKh them. A.N. Bakuleva; 2014. - 342 p.

- Peña E. et al. ALCAPA syndrome: not just a pediatric disease //Radiographics. – 2009. – T. 29. – No. 2. – pp. 553-565.

- Quah JX et al. The management of the older adult patient with anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery syndrome: a presentation of two cases and review of the literature //Congenital heart disease. – 2014. – T. 9. – No. 6. – pp. E185-E194.

- Alsara O. et al. Surviving sudden cardiac death secondary to anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: a case report and literature review //Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care. – 2014. – T. 43. – No. 5. – pp. 476-480.

- Cowles RA, Berdon WE Bland-White-Garland syndrome of anomalous left coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA): a historical review //Pediatric radiology. – 2007. – T. 37. – No. 9. – pp. 890-895.

- Hoffman JIE Electrocardiogram of anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery in infants //Pediatric cardiology. – 2013. – T. 34. – No. 3. – pp. 489-491.

- Hekim N. et al. Whole exome sequencing in a rare disease: A patient with anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (Bland-White-Garland Syndrome) //Omics: a journal of integrative biology. – 2021. – T. 20. – No. 5. – pp. 325-327.

Reasons for appearance

There is no main provoking cause against which the pathological condition arises. Most doctors are inclined to believe that the disease develops during the uterine period.

As all organs and systems form in the child’s body, sinusoidal messages (capillaries) are formed, which must close at a certain period. If this does not happen, a coronary pulmonary fistula develops. Blood vessels are vital to the human body; they maintain normal blood flow throughout the body.

Another reason for the formation of arteriopulmonary fistula is various defects of the cardiovascular system. Pathological conditions are characterized by the formation of shunts between the coronary vessels and the ventricles.

Provoking factors that increase the risk of coronary pulmonary fistula:

| Name | Causes |

| Congenital fistula |

|

| Acquired |

|

Coronary pulmonary fistula in a child also occurs due to various disorders and disruptions in the circulatory system (pulmonary atresia). A pediatric cardiologist will help you establish an accurate diagnosis and select the most effective treatment.

Diagnostics

It is important to differentiate the disease, since many pathological processes are accompanied by similar symptoms. Diagnosis of coronary pulmonary fistula involves examination of the patient and instrumental examination.

| Name | Description |

| Auscultation of the heart | Listening to a systole-diastolic murmur by a specialist allows one to identify its distinctive features. When the fistula enters the atria, the systolic murmur increases, and the diastolic murmur increases into the ventricles. The maximum intensity of noise depends on the location of the fistula drainage. |

| Phonocardiography | A diagnostic method that helps identify pathological fistulas, their size and the degree of expansion of the hole. |

| Ultrasound examination with Dopplerography | The specialist examines the heart, evaluates its functioning and identifies abnormalities, fistulas (pathological shunts). On an ultrasound, the doctor also sees the expansion of the affected coronary artery. |

| Electrocardiography | A diagnostic method that allows you to record specific changes in the functioning of the heart during the formation of large fistulas. |

| Coronary angiography | The study allows you to obtain a three-dimensional three-dimensional image of the coronary vessels and the formation of a pathological fistula. |

| Multislice computed tomography (MSCT) | The most informative method of examining the heart, which allows you to view the organ in three projections. The same applies to blood vessels. |

Coronary pulmonary fistula in a child

During the examination, the doctor obtains maximum information through auscultation of the heart. Large fistulas provoke the appearance of pathological murmurs in the heart and its tones are muffled.

A coronary pulmonary fistula in a child is diagnosed by a pediatrician together with a cardiologist. Specialists assess the patient’s condition based on the results of comprehensive diagnostics and select the most effective therapeutic methods.

Methods for diagnosing arteriovenous fistula

Magnetic resonance imaging

The doctor may hear the sound of blood flow over the area of the suspected arteriovenous fistula. The movement of blood through the AV fistula creates sounds similar to the noise of a car engine.

If the doctor hears this noise, then you will need to undergo additional examination methods, such as:

- Ultrasound

is the most effective and common method for identifying arteriovenous fistulas of the upper and lower extremities. In this study, an instrument called a transducer is placed against the skin. The transducer emits high-frequency sound waves that bounce off red blood cells, allowing the speed of blood flow to be measured. - Computed tomography (CT).

A CT scan allows you to see whether the blood flow is bypassing the capillaries. You will be given an injection of contrast, this is the drug that is visible on the CT scan. The CT scanner will then move to take pictures of the suspected diseased artery. After this, the images will be sent to a computer monitor for evaluation by your doctor. - Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).

An MRA may be used if your doctor suspects you have an arteriovenous fistula in an artery deep under the skin. This study allows you to examine the soft tissues of the body. MRA works on the same principle as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but involves the use of a special drug (dye) to create images of blood vessels. During an MRA or MRI, you lie on a table inside a long tube-like machine that produces a magnetic field. An MRI machine uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create images of tissue in your body. Using these images, the doctor will be able to detect an arteriovenous fistula.

Prevention

It is impossible to prevent congenital abnormalities.

But there are useful tips that reduce the risk of disorders during pregnancy planning and gestation:

- It is necessary to completely eliminate bad habits (alcohol, drugs, tobacco products).

- It is important not to self-treat any disease. The regimen and course of therapy are selected by the doctor, taking into account the patient’s condition and the established diagnosis. Many medications have a negative effect on the fetus.

- In the case of a hereditary predisposition to the appearance of a coronary pulmonary fistula, a woman needs to visit her doctor for preventive purposes and undergo examinations.

- It is necessary to adhere to a healthy lifestyle, eat properly and rationally, and exercise moderately.

Pathological shunts require timely treatment. Preventative examinations will help identify changes at an early stage. People who are in the risk category are advised to avoid strenuous physical activity.

Acquired vascular anomalies can be prevented if the necessary surgical intervention and biopsy are performed by a qualified surgeon.

Treatment methods

Treatment of coronary pulmonary fistula in children and adults in most cases is carried out surgically. Drug treatment helps eliminate the clinical symptoms that accompany the disease and prevent serious complications. With small fistulas, the patient has a better chance of a favorable prognosis.

Medications

Coronary pulmonary fistula in a child is treated with medication if pathological fistulas are diagnosed small in size and at an early stage. It is important to strictly adhere to medical prescriptions, since many drugs cause side effects. Patients are prescribed diuretics, beta blockers and vasodilators.

Other methods

For coronary pulmonary fistula, the diameters of which exceed 2 mm, the main treatment is surgery. The technique of the operation depends on the size of the resulting fistula, its location and the number of pathological shunts. Before the operation, specialists also take into account the individual characteristics of the patient’s body.

The main goal of surgery is to remove the coronary pulmonary fistula to prevent congestion. Pathological changes provoke the development of heart failure.

Surgical treatment of coronary pulmonary fistulas in children and adults is carried out using the following methods:

| Name | Description |

| Transcatheter occlusion | Surgery is performed when diagnosing simple coronary-pulmonary fistulas in children without concomitant heart pathologies or defects. Abnormal vascular openings are closed with obturates, special spirals or removable cylinders. |

| Surgical correction | An open type of surgical intervention, which is performed in most cases for multiple pathological fistulas with the formation of an aneurysm on large blood vessels. During the operation, the surgeon completely eliminates the abnormal fistulas that have appeared. |

Open surgery shows good results, even in the presence of concomitant diseases of the cardiovascular system. After surgical treatment, the patient faces a long rehabilitation period, during which it is important to strictly adhere to the doctor’s recommendations in order to recover safely.

Surgical treatment ends in death in 2% of cases. According to medical statistics, 3.6% is myocardial infarction, the risk of which increases after surgery.

Many patients also face serious complications after surgery:

- violation of the integrity of the pathological fistula;

- ventricular fibrillation;

- formation of a blood clot in the coronary artery;

- cardiac ischemia.

In adult patients, the consequences of surgery are more common than in children, but in some cases this is the only relevant method of treatment.

Endovascular closure of paraprosthetic aortic fistula with SearCare PDA occluder

- S.A. Abugov

- V.V. Ruskin

- M.V. Puretsky

- Frolova Yu.V.

- G.V. Mardanyan

- T.A. Buravikhina

- Dombrovskaya A.V.

- Dzemeshkevich Sergei Leonidovich

Summary

Paravalvular fistula after aortic valve replacement increases mortality and may lead to heart failure requiring treatment. Reoperation is still the treatment of choice, but it carries a high risk of complications. Recently, endovascular (percutaneous) closure of the paraprosthetic fistula using occluders (or spirals) has become an alternative to surgical treatment. We describe endovascular closure of a paraprosthetic aortic fistula in a 72-year-old female patient undergoing aortic valve replacement with a biologic prosthesis. A patient with a high risk of reoperation due to concomitant pathology underwent endovascular implantation of a SearCare PDA occluder 8×10 mm under the control of aortography and transesophageal echocardiography. The short- and medium-term results of the operation were good, with a decrease in the degree of aortic regurgitation from AR 3-4 to AR 1. Endovascular closure of a paraprosthetic fistula using occluders is a feasible but technically challenging procedure. We believe that an assessment of the risks and benefits of reoperation and the endovascular method of closure should be carried out by a consultation with the participation of cardiovascular and endovascular surgeons.

Key words: aortic valve replacement, paraprosthetic fistula, endovascular occluder

Klin.

and experiment. hir. Journal them. acad. B.V. Petrovsky. - 2013. - No. 1. - P. 87-90. Aortic valve replacement (AVR) is the most common operation for patients with valvular pathology. Practice guidelines recommend the use of biological prostheses in patients over 65 years of age [1]. As the population's life expectancy increases, the number of such operations is growing rapidly. Thus, among patients over 70 years of age, the number of patients with biological heart valves has increased significantly - from 87% in 2004-2005. up to 95% in 2008-2009 [2]. As the number of operations increases, the cases of prosthetic dysfunction due to valve-dependent complications also increase. One of the main complications after AVR is a paraprosthetic fistula, which has a significant impact on the early clinical and long-term outcome. The presence of paraprosthetic aortic regurgitation after AVR is associated with increased patient mortality [3, 4]. Although repeated open surgery is considered the standard treatment for this complication, it is often associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality. An alternative to reoperation can be an endovascular method for closing paraprosthetic fistulas.

Clinical case

Patient N., 72 years old.

She complained of shortness of breath and pressing pain in the chest with minimal physical activity, sometimes at rest, including at night.

History: more than 15 years ago, aortic stenosis was first detected during echocardiography. Subsequently, the severity of the stenosis progressed, and the patient refused surgical interventions that were repeatedly offered. According to echocardiography data from 2009, the peak pressure gradient (PGr) at the aortic valve (AV) is 84 mm Hg. Art., from 2011 - 100 mm Hg. Art.

24.10.2012:

according to ECG data - incomplete blockade of the anterior left branch of the His bundle, hypertrophy of the left ventricular myocardium;

according to X-ray of the chest - horizontal position of the heart, increase in volume due to the left ventricle. AC calcification;

according to echocardiography - EF 65%, TMZH - 1.2 cm, LVAD - 1.3 cm. AK: the leaflets are changed, there is pronounced calcification of the leaflets with a transition to the aortic fibrous ring, the base of the anterior mitral leaflet; PGr - 147/93 mm Hg. Art. Aortic insufficiency degree I;

according to coronary angiography - the anterior descending artery, circumflex artery, right coronary artery - without hemodynamically significant stenoses.

06.11.2012

— AK replacement surgery with biological prosthesis SorinMitroflow No. 19:

according to intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography after surgery on the Mitroflow 19 AK prosthesis: Vmax - 2.5 m/s, PGr - 20.0/11.6 mm Hg. Art. With CDK: in the area of the commissure of the right coronary (RC) and non-coronary (NC) leaflets, a paraprosthetic fistula with a diameter of 2-3 mm with regurgitation up to I-II degrees was identified.

In the postoperative period

an increase in prosthesis dysfunction was noted:

according to control transesophageal echocardiography - AC prosthesis: Vmax - 3.4 m/s, PGr - 45/24 mm Hg. Art. With CDK: aortic insufficiency of III-IV degree. In the RC projection, a paraprosthetic fistula with a width of 6.5 mm is identified. The regurgitant jet occupies almost the entire LVOT and reaches a level below the heads of the papillary muscles.

Taking into account the very high risk of re-operation, a consultation consisting of cardiac surgeons, endovascular surgeons, cardiologists, anesthesiologists and resuscitators made a decision on endovascular closure of the paraprosthetic fistula.

28.11.2013

— closure of the paraprosthetic fistula with the SearCare PDA system:

procedure

— under local anesthesia with a 0.5% novocaine solution, the right common femoral artery was punctured and catheterized. The introducer is installed.

A control aortography was performed, which visualized an aortic paraprosthetic fistula with grade III regurgitation (Fig. 1).

On transesophageal echocardiography, the size of the defect was 6.5 mm. The diagnostic catheter was passed through the paraprosthetic fistula (Fig. 2).

Then, a SearCare PDA occluder measuring 8x10 mm was passed through the delivery system under the control of RG and EchoCG (Fig. 3).

The control transesophageal echocardiography showed good fixation of the occluder and grade II aortic insufficiency. The diameter of the residual paraprosthetic fistula is 3 mm. Central transprosthetic regurgitation VC - 5mm. Thus, a 2-fold reduction in the diameter of the paraprosthetic fistula was obtained.

Control echocardiograms in the postoperative period showed a decrease in the degree of aortic insufficiency. Before the patient was discharged, according to transthoracic echocardiography, there was grade I aortic insufficiency.

The patient is observed on an outpatient basis; currently, shortness of breath during normal physical activity does not bother her.

After 3 months:

According to the control echocardiography, the left ventricle: EF - 62%, LVSD - 0.9 cm, LVAD - 1.0 cm. Local contractility is not impaired.

AK prosthesis: Vmax - 3.3 m/s, PGr - 44/24 mm Hg. Art. With CDK: aortic insufficiency of the 1st degree.

Mitral insufficiency degree I. Tricuspid insufficiency degree I. Pulmonary valve insufficiency grade 0-I. There is no pulmonary hypertension.

Discussion

Currently, the main treatment method for patients with dysfunction of artificial heart valves is surgical correction. However, despite the progress achieved in cardiac surgery, a high mortality rate remains, which in case of paraprosthetic fistulas reaches, according to various authors [5-10], more than 10%. An alternative to surgical correction of paraprosthetic fistulas can be the endovascular method.

However, it should be noted that endovascular correction of paraprosthetic fistulas has not been fully studied. Currently, there is no data on the long-term results of the method. The procedure takes a lot of time, is technically complex, and requires coordinated work of x-ray surgeons and functional diagnostic specialists. Successful occluder positioning is achieved in 62-92% of cases [11]. The main benefit of the procedure is to reduce the area of the fistula, which in most patients leads to a decrease in the NYHA functional class of heart failure by one step. The question of the area of the residual fistula remains unresolved: whether it will close over time and what its effect on hemolysis will be. Endothelialization of the occluder can lead to both complete closure of the residual lumen of the fistula (so in theory) and to an increase in the area of the remaining lumen due to the radial force of the device. Currently, endovascular closure of a paraprosthetic fistula is feasible and may be the method of choice in patients at high risk of reoperation [12-15]. In each situation, a multidisciplinary approach is required (with the participation of a cardiac surgeon, an endovascular surgeon, a specialist in functional diagnostics) with an assessment of the risks and benefits of reoperation, as well as endovascular closure of the paraprosthetic fistula.

Literature

1. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012) // Eur. Heart J. - 2012. - Vol. 33. - P. 2451-2496.

2. Dunning J., Gao N., Chambers J. et al. Aortic valve surgery: Marked increases in volume and signiflcant decreases in mechanical valve use — an analysis of 41,227 patients over 5 years from the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland National database // J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. - 2011. - Vol. 142(4). — P. 776-782. e3

3. Tamburino C., Capodanno D., Ramondo A. et al. Incidence and predictors of early and late mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in 663 patients with severe aortic stenosis // Circulation. - 2011. - Vol. 123. - P. 299-308.

4. Zahn R., Gerckens U., Grube E. et al. The German transcatheter aortic valve interventions: registry investigators. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: first results from a multi-centre real-world registry // Eur. Heart J. - 2011. - Vol. 32. - P. 198-204.

5. Pansini S., Ottino G., Forsennati PG et al. Reoperations on heart valve prostheses: An analysis of operative risks and late results // Ann. Thorac. Surg. - 1990. - Vol. 50. - P. 590-596.

6. Cohn LH, Aranki SF, Rizzo RJ et al. Decrease in operative risk of reoperative valve surgery // Ann. Thorac. Surg. - 1993. - Vol. 56. - P. 15-20.

7. Jones JM, O'Kane H, Gladstone DJ et al. Repeat heart valve surgery: Risk factors for operative mortality // J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. - 2001. - Vol. 122. - P. 913-918.

8. Lytle BW, Cosgrove DM, Taylor PC et al. Reoperations for valve surgery: Perioperative mortality and determinants of risk for 1,000 patients, 1958-1984 // Ann. Thorac. Surg. - 1986. - Vol. 42. - P. 632-643.

9. Akins CW, Buckley MJ, Daggett WM et al. Risk of reoperative valve replacement for failed mitral and aortic bioprostheses // Ann. Thorac. Surg. - 1998. - Vol. 65. - P. 1545-1551.

10. Tyers GF, Jamieson WR, Munro AI et al. Reoperation in biological and mechanical valve populations: Fate of the reoperative patient // Ann. Thorac. Surg. - 1995. - Vol. 60. - P. S464-S468.

11. Y. Shapira, R. Hirsch, R. Kornowski et al. Percutaneous closure of perivalvular leaks with Amplatzer occluders: feasibility, safety, and short term results // J. Heart Valve Dis. - 2007. - Vol. 16(3). — P. 305-313.

12. Pate GE, Al Zubaidi A, Chandavimol M et al. Percutaneous closure of prosthetic paravalvular leaks: case series and review // Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. - 2006. - Vol. 68(4). — P. 528-533.

13. Webb JG, Pate GE, Munt BI Percutaneous closure of an aorticprosthetic paravalvular leak with an Amplatzer duct occluder // Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. - 2005. - Vol. 65(1). — P. 69-72.

14. Sorajja P, Cabalka AK, Hagler DJ et al. Successful percutaneous repair of perivalvular prosthetic regurgitation // Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. - 2007. - Vol. 70(6). — P. 815-823.

15. Dussaillant GR, Romero L., Ramirez A., Sepulveda L. Successful percutaneous closure of paraprosthetic aorto-right ventricular leak using the Amplatzer duct occluder // Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. - 2006. - Vol. 67(6). — P. 976-980

Possible complications

The lack of timely comprehensive diagnosis and properly selected therapy will lead to serious consequences. It is important for patients to be under the supervision of a cardiologist, especially if they are at risk.

Coronary pulmonary fistula in a child or adult provokes the following complications:

| Name | Description |

| Coronary aneurysm | A pathological condition characterized by protrusion of the wall of a blood vessel. The main reason is its thinning or stretching. Without timely treatment, the risk of rupture of a blood vessel increases, which will lead to the death of a person. |

| Chronic myocardial ischemia | Functional and organic damage to heart tissue occurs. In most cases, the pathological condition is a consequence of chronic circulatory disorders. |

| Congestive heart failure | The pathological condition occurs against the background of chronic overload of the heart. |

| Atherosclerosis of the coronary artery | A disease that develops as a result of coronary pulmonary fistula in 20-30% of cases. |

| Myocardial infarction | A pathological condition in which a focus of ischemic necrosis forms in the area of the heart muscle. The cause is an acute violation of coronary circulation. |

Small fistulas may not be dangerous, but the lack of properly selected therapy will lead to their enlargement, which will lead to possible consequences. Large pathological fistulas that are not diagnosed in a timely manner can lead to death.

Coronary pulmonary fistula is a rare pathological condition. Not only children, but also adults are at risk. Disturbances in the functioning of the cardiovascular system cannot be ignored. It is necessary to immediately visit a therapist or cardiologist, undergo a comprehensive examination and begin treatment.

Types of arteriovenous fistulas, their symptoms

Arteriovenous fistulas can be congenital or acquired.

Congenital arteriovenous fistulas can be located in any part of the body and are often associated with the localization of nevi - birthmarks, melanomas, etc.

ischemia (lack of blood supply) of the limbs and venous hypertension already in the first weeks and months after birth . This may be accompanied by skin pigmentation, enlarged limbs, hyperhidrosis, swelling of the saphenous veins and other symptoms.

The appearance of acquired arteriovenous fistulas (fistulas) can be a consequence of trauma, injury, as well as a consequence of medical procedures - for example, bypass surgery. Also, during surgical operations for hemodialysis, arteriovenous fistulas (fistulas) can be created specifically to ensure the effectiveness of this treatment. Therefore, it is important to undergo surgery by experienced, qualified doctors with modern technical capabilities.

The appearance of large arteriovenous fistulas (fistulas) is accompanied by swelling and redness of the tissue, however, small fistulas (fistulas) may not manifest themselves until heart failure .