Mechanism of development of acute coronary syndrome

Myocardial infarction, which, along with an episode of unstable angina, is included in the concept of acute coronary syndrome, is an exacerbation of coronary heart disease. During myocardial infarction, necrosis of the heart muscle develops due to acute disruption of the blood supply. In most cases, this occurs as a result of atherothrombosis, in which the coronary vessels are partially or completely blocked by a blood clot. The disease is manifested by sudden intense pain in the chest, tachycardia, “cold sweat”, pallor of the skin and a number of other symptoms.

The goal of treating an acute heart attack is to quickly restore blood supply. However, even after blood flow is established, therapy cannot be stopped, since coronary atherosclerosis, which became the foundation for the development of acute coronary syndrome, is chronic.

Stages of development of a heart attack with ST segment elevation

The most acute stage of STEMI

First, a high coronary T appears on the cardiogram. The high coronary T before ST elevation is present for a very short time, so it is not always possible to register it. Then there is an increase in the ST segment, which merges with a high T.

Scheme 2. ECG fragments in the most acute stage of STEMI

Acute stage STEMI

Lasts up to 2-3 days (sometimes up to 2 weeks). The beginning of the acute phase is considered to be the appearance of the Q wave, which reflects the formation of a zone of myocardial necrosis. As the acute phase develops, the Q wave deepens, and the ST segment begins to decline towards the isoline. The T wave becomes negative.

Scheme 3. ECG fragment in the acute stage of STEMI

Subacute stage of STEMI.

Lasts for several weeks. The ECG records a decrease in the ST segment to the level of the isoline. At the same time, a deep negative T wave is formed.

Scheme 4. ECG fragment in the subacute stage

Scar stage STEMI

Dead myocardial cells are replaced by connective tissue, which leads to the formation of a scar. The areas of the myocardium surrounding the scar undergo compensatory hypertrophy. The number of leads on the ECG in which changes associated with a heart attack are recorded is reduced. The Q wave may become less deep, and the T wave returns to the baseline. The formed picture of post-infarction cardiosclerosis on the ECG persists throughout the patient’s life.

Sometimes the ST segment does not reach the isoline and remains elevated almost throughout life. As a rule, the QRS complex takes on the QS form, which may indicate the formation of a cardiac aneurysm.

Scheme 5. ECG fragments with post-infarction changes

Diagram 5 on the left shows a fragment of a cardiogram indicating a myocardial infarction. On the right is a fragment of a cardiogram in which the ST segment has not reached isolia and a QS complex has formed, turning into increased ST. This picture is called a “frozen ECG” and indicates a post-infarction cardiac aneurysm.

Early consequences of myocardial infarction1

Starting from the first hours after a heart attack and up to 3-4 days, early consequences of a heart attack may develop, including:

- acute left ventricular failure, which occurs when the contractility of the heart decreases. When it occurs, shortness of breath, tachycardia, and cough appear;

- cardiogenic shock. This is a severe complication of acute coronary syndrome, developing as a result of a significant deterioration in the contractility of the heart muscle due to extensive necrosis;

- disturbances of cardiac rhythm and conduction are observed in 90% of patients with acute MI.

- Attacks of early post-infarction angina (PSA). PSC is the occurrence or increase in frequency of angina attacks 24 hours and up to 8 weeks after the development of MI.

- pericarditis is an inflammatory process that develops in the outer lining of the heart, the pericardium. It occurs in the first or third day of the disease and can manifest itself as pain in the heart area, which changes with a change in body position, and an increase in body temperature.

In 15-20% of heart attack cases, thinning and bulging of the heart wall occurs, most often of the left ventricle. This condition is called cardiac aneurysm. As a rule, it develops with extensive damage to the heart muscle. Factors predisposing to the development of cardiac aneurysm also include violation of the regime from the first days of the disease, concomitant arterial hypertension and some others.

A special group consists of thromboembolic consequences, in which the lumen of the vessels is completely or partially blocked by blood clots. This often occurs against the background of concomitant varicose veins, blood coagulation disorders and prolonged bed rest.

Due to impaired blood supply, acute coronary syndrome can be complicated by gastrointestinal problems, such as erosions and acute ulcers of the gastrointestinal tract. Mental disorders may also occur - depression, psychosis. They are facilitated by old age and concomitant diseases of the nervous system.

Diagnostics

Inferior, posterior or anterior myocardial infarction is diagnosed in the same way. First, I always collect a medical history and evaluate the patient's complaints. Most often, chest pain alone is enough to raise suspicions.

To confirm my guess, I use auxiliary instrumental and laboratory examinations.

Instrumental methods

The basis for diagnosing any myocardial infarction is an ECG. It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the electrocardiogram in ischemic heart disease. The technique allows you to see on paper or a screen the slightest deviations in the electrical function of the heart, which always occur when the supply of certain areas of the myocardium with blood is disrupted.

Possible changes on the film:

- elevation (rise) or depression (subsidence) of the ST segment relative to the isoline;

- inversion (change of polarity to the opposite) of the T wave;

- formation of a deep and wide (pathological) Q wave.

There are indirect signs on the ECG that may indicate an anterior infarction or damage to the other wall of the left ventricle.

To clarify the location and extent of damage to the heart muscle, I always additionally prescribe the following studies:

- Angiography of the coronary vessels. After contrast is injected into the coronary arteries, I see the blockage site on the monitor screen, which allows me to quickly restore the patency of the vessel using stenting.

- Echocardiography (Echo-CG). Ultrasound examination of the heart allows you to see a decrease or complete absence of contractions of the affected area of the myocardium (hypo- or akinesia).

In 98% of cases, the instrumental methods described above are sufficient to make a final diagnosis.

Laboratory methods

Laboratory tests are excellent assistants in the early stage of disease verification. The most reliable blood test remains for troponin I. The latter is a protein found in cardiomyocytes. When myocardial cells die, troponin enters the blood, where it can be fixed. For more information on how it is made, read the article at the link.

Additional laboratory tests:

- General blood analysis. During a heart attack, the number of leukocytes may increase and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may increase.

- Blood chemistry. The amount of C-reactive peptide, AST, and ALT may increase.

- Coagulogram. The analysis demonstrates the function of blood clotting. In heart attack patients it is often too pronounced.

Among laboratory tests, I, like the vast majority of cardiologists, first of all do a troponin test. Other tests are of secondary importance.

Late consequences of a heart attack

At the end of the acute period of the disease, so-called late consequences may develop. These include complications that appear 10 days after the manifestation of MI and later:

- post-infarction Dressler syndrome occurs 2-6 weeks after the manifestation of myocardial infarction and is manifested by inflammation of the pericardium, pleura, alveoli, joints and other pathological changes;

- thromboendocarditis with thromboembolic syndrome (the appearance of a wall thrombus in the heart cavity, on the heart valves);

- late post-infarction angina, which is characterized by the occurrence or increase in frequency of angina attacks. Its frequency ranges from 20 to 60%.

Some patients who have suffered an acute myocardial infarction are at high risk for developing repeated complications of coronary heart disease and, above all, recurrent myocardial infarction and unstable angina. This is due to the fact that in patients with acute coronary syndrome, along with the presence of an atherosclerotic plaque, which was complicated by a rupture and blocked the lumen of the coronary artery, there are plaques in other arteries. They can be the cause of repeated episodes of cardiovascular events, the probability of which is very high.

Expert advice

My advice to patients is quite simple:

- quit smoking;

- be less nervous about trifles;

- rationalize nutrition: there is no need to give up your favorite dishes, the main thing is moderation;

- undergo regular preventive medical examinations;

- move more and do as much physical exercise as possible.

It is almost impossible to completely protect yourself from a heart attack. However, thanks to the basic points mentioned above, you can not only improve your well-being, but also prevent the progression of more than two dozen internal diseases.

Left ventricular lateral wall infarction

Left ventricular lateral wall infarction with ST elevation, as discussed above, is usually associated with anterior wall infarction. In addition, it can be combined with infarction of the lower or posterior wall. It develops as a result of occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and/or the circumflex coronary artery (LCX).

Isolated lateral wall infarction is less common and is associated with occlusion of the small branches of the LAD or the marginal branch of the LCX.

Scheme 10. Infarction of the lateral wall of the left ventricle

On the cardiogram with a lateral wall infarction, ST elevation is recorded in leads I, aVL, V5-V6. If ST elevation is only in leads I, aVL, but not in leads V5-V6, they speak of a high lateral infarction. A reciprocal decrease occurs in leads III, aVF.

Examples of lateral wall infarction combined with anterior wall infarction were shown above (see ECG 3-5).

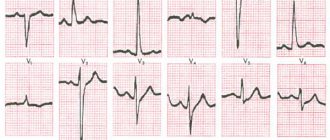

ECG 6. High lateral left ventricular infarction

ECG source.

ECG 6 shows ST elevation in leads I and aVL, as well as reciprocal depression in leads III, aVF. There is no ST elevation in leads V5-V6. These are signs of high lateral left ventricular infarction.

Posterior wall infarction

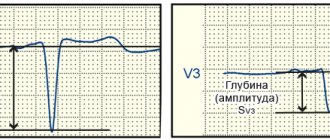

An infarction of the posterior wall, as a rule, develops in combination with an infarction of the lower or lateral wall of the left ventricle. Isolated posterior wall infarction occurs in no more than 10% of cases. However, isolated posterior wall infarction is not always recognized in a timely manner, since it develops infrequently and there is no ST segment elevation on a standard 12-lead cardiogram. To confirm this diagnosis, it is necessary to use additional posterior leads: V7-V9. Posterior wall infarction can be suspected from a 12-lead ECG based on the following signs:

- ST segment depression in leads V1-V3. This ST depression is reciprocal to ST elevation in the accessory posterior leads (V7-V9).

- Tall and usually widened R waves in leads V1-V3.

- The R/S ratio in V2 is greater than 1.

- Positive T wave in leads V1-V3.

ECG 8. Infarction of the posterior and inferior wall of the left ventricle with ST elevation

ECG source.

On ECG 8, ST segment depression, as well as a tall and wide R wave in leads V2-V3, indicate infarction in the posterior wall of the left ventricle. To confirm this diagnosis, a cardiogram was recorded using additional leads V7-V9, where ST elevation was recorded. In addition, in leads III, aVF, slight elevation of the ST segment was also recorded, which indicates involvement of the lower wall of the left ventricle in the process.

ECG 9. Infarction with ST elevation of the lateral and posterior wall of the left ventricle

ECG source.

On ECG 9, ST elevation in leads I, aVL, V5-V6 and reciprocal ST depression in leads III, aVF reflect infarction of the lateral wall of the left ventricle. In addition, there is a decrease in ST in leads V1-V3, which, in combination with high R waves in these same leads, may indicate posterior wall damage. Thus, in this case there is an infarction of the lateral and posterior wall of the left ventricle. To confirm posterior wall infarction, an ECG should be recorded in additional posterior leads (V7-V9).

Interventricular septal infarction

As mentioned above, isolated septal infarction is a rare occurrence (usually septal and anterior wall infarction). Septal infarction develops as a result of occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (LAD). The cardiogram records ST elevation in leads V1-V2.

Scheme 8. Infarction of the interventricular septum

ECG 2. Myocardial infarction of the interventricular septum

ECG source.

On ECG 2, an infarction of the interventricular septum is indicated by pathological Q waves in leads V1-V2 and moderate ST elevation in the same leads. Judging by the ST height and the presence of Q waves, this is a subacute stage of infarction. In addition, in this case there is diffuse ST segment depression in leads I, II, V4-V6 in combination with ST elevation in aVR. This indicates subendocardial myocardial ischemia.