Make an appointment by phone: +7 (343) 355-56-57

+7

- About the disease

- Cost of services

- Sign up

- About the disease

- Prices

- Sign up

Paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia (PVT)

is an absolutely life-threatening rhythm disorder that requires immediate hospitalization.

Along with ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia is the leading cause of circulatory arrest and sudden death in Russia and in the world.

REASONS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF PAROXYSMAL VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

Reasons for the development of PVT:

1. severe diseases of the cardiovascular system:

- myocardial infarction

- cardiomyopathy

- heart defects

- heart failure

- myocarditis (severe)

2. toxic factors:

- frequent alcohol consumption in significant quantities

- inhalation of glue fumes

- narcotic substances

3. cardiac injury

4. medications: cardiac glycosides, antidepressants, flecainide, fluoroquinolones

5. congenital anomalies of the cardiac conduction system (Brugada syndrome)

6. idiopathic VT – the cause of development is unclear

2. Causes of the disease

The following factors are considered to be the causes of paroxysmal tachycardia:

- endocrine disorders;

- transient oxygen starvation of the heart muscle;

- changes in the concentration of electrolytes in the blood;

- heart defects;

- inflammatory diseases of the heart muscle;

- hypertension;

- hereditary factor;

- psycho-emotional factor.

However, in some patients no obvious causes are identified either before the onset of an attack or during life.

Visit our Cardiology page

SYMPTOMS OF PAROXYSMAL VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA AND FIRST AID

If circulatory arrest develops in such patients, resuscitation measures must be started immediately and carried out until doctors arrive. The only effective way to interrupt this arrhythmia is defibrillation

(that is, the application of electric current by a special defibrillator device). But while waiting for the resuscitation team, everyone should be able to help such patients.

Clinically, PVT is manifested by a sudden loss of consciousness and circulatory arrest, that is, such patients do not breathe, they have no pulse and consciousness. In this situation, you must immediately punch the patient's sternum (the narrow, flat bone in the center of the chest) and begin chest compressions (CCM).

.

How is NMS performed:

- the patient should lie on a hard surface

- the person providing assistance intensively presses on the patient’s chest with a frequency of 100 compressions per minute and to a depth of 5-6 cm

- resuscitation is carried out until the arrival of the medical team

Indirect cardiac massage performs the function of a pump and the hands of the resuscitator, in essence, replace the patient’s stopped heart.

Often paroxysms of VT are manifested by recurrent (that is, repeated) fainting, with spontaneous (that is, independent) restoration of consciousness.

Diagnostics

The task of a cardiologist who examines a child with suspected tachycardia is to make sure that the signs he has do not indicate other diseases, for example, bronchial asthma. Also during the examination, he looks for the cause of the disease. To do this, the specialist uses:

- ECG and daily monitoring to analyze how the heart rhythm changes during the normal activity of a small patient;

- EchoCG and MRI to make sure there are no heart pathologies;

- an electrophysiological study to check how the electrical impulse travels through the heart muscle;

- laboratory methods: urine, blood analysis;

- EEG of the brain to make sure that the activity of the central nervous system is not impaired.

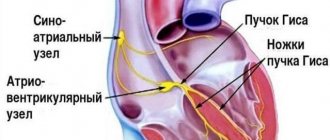

MECHANISMS OF DEVELOPMENT OF PAROXYSMAL VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

Why does a patient's heart stop during PVT?

The mechanism of development of this cardiac arrhythmia is as follows. Due to the damaging factor, foci of damage appear in the myocardium (heart muscle), similar to microinfarctions, changing the overall “electrical background” of the heart.

In this regard, around such foci or in them themselves there are paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia. They cause the heart to beat at a high frequency and the main source of this arrhythmia is in the myocardium of the ventricles of the heart. Unlike the atria, the ventricles are “designed” to work at a frequency of 60-80-100 per minute. With VT, the heart rate exceeds 200 per minute and the heart, of course, cannot work in this mode for a long time. And then it stops. This is sudden cardiac death.

Such a patient can be saved by a timely applied current discharge to the chest through a defibrillator. Many countries around the world have launched a program to prevent sudden cardiac death and train the population in first aid, including in case of sudden cardiac arrest. Unfortunately, in our country only medical workers are skilled in this manipulation.

Clinical variants and incidence of supraventricular tachycardias in children

Supraventricular (supraventricular) tachycardias (SVT) account for 95% of all tachycardias in children and are often paroxysmal in nature. In most cases, SVTs are not life-threatening rhythm disturbances, but may be accompanied by complaints of a sharp deterioration in health and have a pronounced clinical picture.

The term “supraventricular tachycardia” refers to three or more consecutive heart contractions with a frequency exceeding the upper limit of the age norm in children and more than 100 beats per minute in adults, if the participation of the atria or atrioventricular (AV) junction is required for the occurrence and maintenance of tachycardia.

SVT includes tachycardias that occur above the bifurcation of the His bundle, namely in the sinus node, atrial myocardium, AV junction, trunk of the His bundle, emanating from the mouths of the vena cava, pulmonary veins, and also associated with additional conduction pathways.

Supraventricular tachycardia is a common form of cardiac arrhythmia in children and adults. The prevalence of paroxysmal SVT in the general population is 2.25 cases per 1000 people, with 35 new cases occurring per year per 100,000 population [1]. The incidence of SVT in children, according to various authors, varies significantly and ranges from 1 case in 25,000 children to 1 case in 250 children [2, 3].

In practice, it is convenient to use the clinical and electrophysiological classification of SVT, which systematizes individual nosological forms of tachycardias, indicating their localization, electrophysiological mechanism, various subtypes and variants of the clinical course [4].

Clinical and electrophysiological classification of supraventricular tachycardias in children:

I. Clinical options for SVT:

1. Paroxysmal tachycardia:

- stable (duration of attack 30 s or more);

- unstable (duration of attack less than 30 s).

2. Chronic tachycardia:

- constant;

- permanently returnable.

II. Clinical and electrophysiological types of SVT:

1. Sinus tachycardia:

- sinus tachycardia (functional);

- chronic sinus tachycardia;

- sinoatrial reciprocal tachycardia.

2. Atrial tachycardia:

- focal (focal) atrial tachycardia;

- multifocal or chaotic atrial tachycardia;

- incisional atrial tachycardia;

- atrial flutter;

- atrial fibrillation.

3. Tachycardia from the AV junction:

- atrioventricular nodal reciprocal tachycardia: - typical; - atypical;

- focal (focal) tachycardia from the AV junction: - postoperative; - congenital; - “adult” form.

4. Tachycardia with the participation of accessory pathways (Wolf–Parkinson–White syndrome (WPW), atriofascicular tract and other accessory pathways (ADP)):

- paroxysmal orthodromic AV reciprocal tachycardia with the participation of AP;

- chronic orthodromic AV reciprocal tachycardia with the participation of “slow” AP;

- paroxysmal antidromic AV reciprocal tachycardia with the participation of AP;

- paroxysmal AV reciprocal tachycardia with pre-excitation (involving several APs).

According to the nature of the course, tachycardias are divided into paroxysmal and chronic. Paroxysmal tachycardia has a sudden onset and end of an attack. Attacks of tachycardia are considered stable if they last more than 30 seconds, and unstable if their duration is less than 30 seconds. The clinical picture of paroxysmal tachycardia is quite diverse. In children of the first year of life, during an attack of tachycardia, anxiety, lethargy, refusal to feed, sweating during feeding, and pallor may be observed. In young children, attacks of tachycardia may be accompanied by pallor, weakness, sweating, drowsiness, and chest pain. In addition, children quite often emotionally and figuratively describe attacks, for example, as “heart in the tummy”, “jumping heart”, etc. School-age children can usually talk about all the clinical manifestations of an attack of tachycardia. Often attacks of tachycardia are provoked by physical and emotional stress, but they can also occur at rest. When asked about the heart rate during an attack of tachycardia, children and their parents usually answer that the pulse “cannot be counted”, “cannot be counted”. Sometimes attacks of tachycardia occur with a pronounced clinical picture, accompanied by weakness, dizziness, darkening of the eyes, syncope, and neurological symptoms. Loss of consciousness occurs in 10–15% of children with SVT, usually immediately after the onset of a paroxysm of tachycardia or during a long pause in the rhythm after its cessation.

Chronic tachycardia does not have an acute beginning and end of the attack; it drags on for a long time and can last for years. Chronic tachycardias are divided into constant (continuous) and constant-recurrent (continuously recurrent). Tachycardia is said to be permanent if it accounts for most of the time of day and represents a continuous tachycardic chain. With the constantly recurrent type of tachycardia, its circuits are interrupted by periods of sinus rhythm, but tachycardia can also occupy a significant portion of the day. This division of chronic tachycardia into two forms is somewhat arbitrary, but has a certain clinical significance, since the more time of day the tachycardia occupies and the higher the heart rate, the higher the risk of the child developing secondary arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy and progressive heart failure. Quite often, chronic forms of SVT occur without distinct symptoms and are diagnosed after the first signs of heart failure appear.

In most cases with SVT, the QRS complexes are narrow, but with aberrant impulse conduction they can widen. The heart rate (HR) during tachycardia depends on the age of the children. In newborns and children of the first years of life, heart rate during paroxysmal tachycardia is usually 220–300 beats/min, and in older children it is 180–250 beats/min. In chronic forms of tachycardia, heart rate is usually somewhat lower and amounts to 200–250 beats/min in children of the first years of life and 150–200 beats/min in older ages.

Most often, SVT must be differentiated from functional sinus tachycardia, which is usually a normal physiological response to physical and emotional stress due to an increase in sympathetic influences on the heart. At the same time, sinus tachycardia can signal serious illnesses. It is a symptom and/or compensatory mechanism of the following pathological conditions: fever, arterial hypotension, anemia, hypovolemia, which can be the result of infection, malignant processes, myocardial ischemia, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, shock, thyrotoxicosis and other conditions. It is known that the heart rate has a direct relationship with body temperature; for example, when the body temperature of a child older than two months increases by 1 °C, the heart rate increases by 9.6 beats/min [5]. Sinus tachycardia is provoked by various stimulants (caffeine, alcohol, nicotine), the use of sympathomimetic, anticholinergic, some antihypertensive, hormonal and psychotropic drugs, as well as a number of toxic and narcotic substances (amphetamines, cocaine, ecstasy, etc.). Functional sinus tachycardia usually does not require special treatment. The disappearance or elimination of the cause of sinus tachycardia in most cases leads to the restoration of the normal frequency of sinus rhythm. Sometimes children experience chronic sinus tachycardia, in which the sinus rate does not correspond to the level of physical, emotional, pharmacological or pathological influence. Sinoatrial reciprocal tachycardia is extremely rarely recorded, usually having an unstable paroxysmal course.

Atrial tachycardia in children is often chronic and difficult to treat with medication, can lead to congestive heart failure, and is the most common cause of secondary arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Therefore, despite the relatively low incidence, atrial tachycardia is a serious problem in pediatric arrhythmology. The most common type of atrial tachycardia is focal (ectopic) atrial tachycardia, which accounts for 15% of all SVT in children under one year of age and 10% in children aged one to five years [6].

Focal atrial tachycardia is a relatively regular atrial rhythm with a rate above the upper normal for age, usually between 120 and 300 bpm. In this case, frequent P waves of non-sinus origin, located in front of the QRS complexes, are recorded on the ECG. The morphology of P waves depends on the location of the tachycardia focus. With the simultaneous functioning of several atrial rhythm sources, multifocal (multifocal) atrial tachycardia occurs. This rather rare form of tachycardia is well known as “chaotic atrial tachycardia”. Chaotic atrial tachycardia is an irregular atrial rhythm with a continuously varying frequency from 100 to 400 beats per minute with variable AV conduction of atrial impulses with a frequency of an also irregular ventricular rhythm of 100–250 beats/min. Atrial flutter is a regular, regular atrial rhythm, usually between 250 and 450 beats per minute. With typical atrial flutter on the ECG, instead of P waves, “sawtooth” F waves are recorded with the absence of an isoline between them and with a maximum amplitude in leads II, III and aVF. Incisional (postoperative) atrial tachycardia occurs in 10–30% of children after correction of congenital heart disease (CHD), during which surgical manipulations were performed in the atria. Incisional tachycardias can appear both in the early postoperative period and several years after surgery. They are a serious problem and largely determine mortality after cardiac surgery. Quite rarely, children experience atrial fibrillation, which is chaotic electrical activity of the atria with a frequency of 300–700 per minute, while f waves of different amplitudes and configurations are recorded on the ECG without an isoline between them. Atrial fibrillation leads to a decrease in cardiac output due to loss of atrial systole and arrhythmia itself. Another serious danger of atrial fibrillation is the risk of thromboembolic complications.

The AV junction is associated with the occurrence of two tachycardias that are different in electrophysiological mechanism and clinical course: AV nodal reciprocal tachycardia and focal tachycardia from the AV junction. Paroxysmal AV nodal reentrant tachycardia accounts for 13–23% of all SVTs [2, 6]. Moreover, the incidence of this form of tachycardia increases with age - from isolated cases in children under two years of age to 31% of all SVT in adolescents [6, 7]. The occurrence of this tachycardia is based on the division of the AV connection into zones of fast and slow impulse conduction, which are called the “fast” and “slow” paths of the AV connection. These pathways form a re-entry circle, and depending on the direction of movement of the impulse, typical and atypical forms of AV nodal reciprocal tachycardia are distinguished. Focal tachycardia from the AV junction is associated with the occurrence of foci of pathological automatism or trigger activity in the area of the AV junction and is quite rare.

The most common type of SVT in children in all age groups is paroxysmal AV reentrant tachycardia involving an accessory AV junction (AVJ), which is a clinical manifestation of WPW syndrome. In half of the cases, this type of tachycardia occurs in childhood; it accounts for up to 80% of all SVT in children under one year of age and 65–70% in older age [6, 8].

In orthodromic AV reciprocal tachycardia, the impulse is conducted anterogradely (from the atria to the ventricles) through the AV node, and retrogradely (from the ventricles to the atria) returns through the AP. The ECG shows tachycardia with narrow QRS complexes. In children of the first year of life, the heart rate during tachycardia is usually 260–300 beats/min, in adolescents it is lower - 180–220 beats/min. Attacks of tachycardia can begin either at rest or be associated with physical and emotional stress. The beginning, like the end of the attack, is always sudden. The clinical picture is determined by the age of the child, heart rate, and duration of attacks. In a more rare variant, antidromic AV reciprocal tachycardia, the impulse is conducted anterogradely along the AP and returns through the AV node. In this case, the ECG shows tachycardia with wide, deformed QRS complexes.

We analyzed the incidence of various types of tachycardia in 525 children with SVT examined during the period 1993–2010. in the department of surgical treatment of complex cardiac arrhythmias and cardiac pacing in St. Petersburg State Healthcare Institution “City Clinical Hospital No. 31” (table).

Pathological forms of sinus tachycardia were diagnosed in 25 (4.7%) children, atrial tachycardia - in 75 (14.3%) children, tachycardia from the AV junction - in 163 (31.1%) children, tachycardia involving the APP - in 262 (49.9%) children. According to the nature of the course, 445 (84.8%) children had paroxysmal tachycardia, 80 (16.2%) had chronic tachycardia. It should be noted that functional sinus tachycardia is included in the classification of SVT, but is not taken into account when analyzing the structure of SVT due to the absolute prevalence over other forms of tachycardia, because it is observed in every child with normal sinus node function, for example, during physical activity or emotional stress .

257 (48.9%) children had WPW syndrome and its clinical manifestation was paroxysmal AV reciprocal tachycardia with the participation of an additional AV connection.

157 (29.9%) children were diagnosed with AV nodal reentrant tachycardia: 149 had the typical form, 8 had variants of the atypical form. 6 (1.1%) children had chronic focal tachycardia from the AV junction.

In 75 (14.3%) children, various types of atrial tachycardia were observed: chronic focal atrial tachycardia in 36 children, paroxysmal focal atrial tachycardia - in 15 children, incisional atrial tachycardia - in 2 children, atrial fibrillation - in 11 children, atrial flutter - in 9 children, chaotic atrial tachycardia - in 2 children. 2 (0.4%) children had sinoatrial reentrant tachycardia, 23 (4.4%) had chronic sinus tachycardia.

Considering that in St. Petersburg the overwhelming number of children with tachycardia were examined in our center, we can imagine an approximate epidemiological situation in the city according to SVT. 800 thousand children live in St. Petersburg. Approximately 32 children presented with new cases of SVT per year, which amounted to 1 case per 25,000 children.

From 2000 to 2010, during each year, from 14 to 28 children with WPW syndrome (average 19.4 ± 4.2 children) and from 8 to 16 children with paroxysmal AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (average 10.7 ± 2.8 children). Based on the child population of St. Petersburg, an average of 2 new cases of WPW syndrome and 1 case of paroxysmal AV nodal reentrant tachycardia per 80,000 children were detected per year.

Thus, supraventricular tachycardias in children have many clinical and electrophysiological variants. The first place in terms of frequency of occurrence is occupied by WPW syndrome, the second place is paroxysmal AV nodal reciprocal tachycardia, the third place is atrial tachycardia. According to our study, supraventricular tachycardias in children had the following structure: according to localization of occurrence: 4.7% - sinus tachycardias, 14.3% - atrial tachycardias, 31.1% - tachycardias from the AV junction, 49.9% - tachycardias with participation of the DPP; according to the clinical course: 84.8% - paroxysmal tachycardia, 15.2% - chronic tachycardia. Paroxysmal AV reciprocal tachycardia with the participation of an additional AV connection (WPW syndrome) accounted for 48.9% of all SVTs and 57.8% of paroxysmal forms of SVT. Systematization of various forms of tachycardia in children is of great clinical importance, as it allows one to navigate their diversity and helps to make a consistent differential diagnosis. Accurate verification of the type of tachycardia plays a decisive role in predicting the course of the disease, choosing antiarrhythmic therapy and assessing the effectiveness and safety of catheter ablation.

Literature

- Orejarena LA, Vidaillet HJ, DeStefano F. et al. Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in general population // J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998. Vol. 31, No. 1. P. 150–157.

- Ludomirsky A. Garson A. Supraventricular tachycardia // Pediatric Arrythmias: Electrophysiology and Pacing. Ed. by PC Gillette, A. Garson. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1990, pp. 380–426.

- Bauersfeld U., Pfammatter J.-P., Jaeggi E. Treatment of supraventricular tachycardias in the new millennium - drugs or radiofrequency catheter ablation? //Eur. J. Pediatr. 2001. V. 160. P. 1–9.

- Kruchina T.K., Vasichkina E.S., Egorov D.F. Supraventricular tachycardia in children: educational manual. Ed. prof. G. A. Novik. St. Petersburg: SPbGPMA, 2011. 60 p.

- Hanna C., Greenes D. How much tachycardia in infants can be attributed to fever? //Ann. Emerg. Med. 2004. V. 43. P. 699–705.

- Ko JK, Deal BJ, Strasburger JF, Benson DW Supraventricular tachycardia mechanisms and their age distribution in pediatric patients // Am. J. Cardiol. 1992. Vol. 69, No. 12. P. 1028–32.

- Kruchina T.K., Egorov D.F., Gordeev O.L. et al. Features of the clinical course of paroxysmal atrioventricular nodal reciprocal tachycardia in children // Bulletin of Arrhythmology. 2004. No. 35, appendix. B, p. 236–239.

- Rodriguez L.-M., de Chillou C., Schlapfer J. et al. Age at onset and gender of patients with different types of supraventricular tachycardias // Am. J. Cardiol. 1992. Vol. 70. P. 1213–1215.

T. K. Kruchina *, **, Candidate of Medical Sciences G. A. Novik ***, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor D. F. Egorov *, ****, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

*Research Laboratory of Surgery, **St. Petersburg State Healthcare Institution “City Clinical Hospital No. 31”, ***St. Petersburg State Pediatric Medical Academy, ****National Research Center of St. Petersburg State Medical University named after. Academician I. P. Pavlov, St. Petersburg

Contact information for authors for correspondence

TREATMENT OF PAROXYSMAL VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

If VT develops, emergency hospitalization and immediate restoration of sinus rhythm are necessary.

The rhythm is restored either with medication or by

electropulse therapy (EPT)

.

An antiarrhythmic drug (amiodarone (cordarone)) is administered intravenously. Then, to prevent the re-development of arrhythmia, the patient takes this drug in monotherapy or with other drugs.

EIT uses a current discharge through the chest. The patient is put into medicated sleep, then defibrillator electrodes are applied and a shock is applied. This method is based on the fact that the basis for the development of PVT is the electrical instability of the myocardium.

The current discharge produces a kind of “shake-up” of the myocardium, suppressing “unauthorized” sources of arrhythmia. After EIT, also to prevent relapse (re-development) of arrhythmia, the patient takes antiarrhythmic drugs.

of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) is based on the principle of EIT.

with PVT.

A small device resembling a pacemaker is implanted under the skin, and electrodes from it “descend” into the heart through the blood vessels. If there is no arrhythmia, then this device is “silent”. If a paroxysm of ventricular tachycardia develops, the ICD is triggered and delivers a current discharge to the heart, thereby suppressing the source of the arrhythmia. Thanks to the ICD, the patient is protected from the risk of sudden cardiac arrest and, in fact, carries a small defibrillator with him at all times. The implantation of these devices is carried out by cardiovascular surgeons in specialized arrhythmology centers, which include the New Hospital.

ICD implantation does not require anesthesia; it is performed through a small incision in the skin; the patient can engage in normal activities the very next day after surgery. However, after ICD implantation, the patient must be under the supervision of a cardiac surgeon-arrhythmologist, and such supervision is also available in our clinic.

Paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia can be unstable, i.e. short-term, and go away on its own. But observation and treatment are required, since there is a risk of its re-development and threat to the patient’s life.

Sometimes cardiac surgeons resort to ablation of PVT foci, that is, they “cauterize” the arrhythmogenic focus using cold exposure (cryodestruction) or laser. These manipulations are also performed in cardiac surgery hospitals. And further observation and treatment is required under the guidance of a cardiac surgeon-arrhythmologist.

A special type of VT is paroxysms of this rhythm disorder against the background of congenital anomalies of the conduction system of the heart (for example, with Brugada syndrome). Cardiac conduction system (CCS)

- “electrical wiring” in the heart that converts an electrical impulse into myocardial contraction. With Brugada syndrome, the patient is born “prepared” to develop life-threatening arrhythmias, incl. PVT.

The “wiring” in such patients “sparks.” This is a paroxysm of arrhythmia

. Before exposure to a provoking factor (for example, taking medication), the patient is healthy, but in the event of contact with this factor, the preparation for arrhythmia is realized and it develops. Often the first and last time in my life.

Therefore, cardiologists and arrhythmologists pay such attention to family history. In the presence of congenital anomalies of PSS, the fact of death at a young age from unknown causes of one of the relatives, especially the first or second degree of kinship, is alarming.

The presence of an electrocardiogram (ECG) taken at a speed of 50 mm/sec is a mandatory part of any consultation with a cardiologist and arrhythmologist. Already when analyzing a regular ECG, the doctor recognizes the signs of Brugada syndrome and helps his patient in a timely manner.

Symptoms

The nature of the manifestation of the symptoms of this disease is largely determined by the degree of its severity, duration and characteristics of the course.

Symptoms of ICD10 tachycardia are the presence of rapid heartbeat, a feeling of heaviness and pain in the left side. A person may also experience a feeling of shortness of breath, shortness of breath and weakness.

Pregnant women with similar problems experience disturbed sleep, increased fatigue, decreased appetite and performance, and a general deterioration in their psycho-emotional state. Children may experience some moodiness, depression and low mobility.

PREVENTION OF PAROXYSMAL VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

- Knowledge of family history.

If there have been sudden deaths in the family (especially in first- or second-degree relatives at a young age), then contact a cardiologist to identify the risk of developing PVT. - Prevention of the development of cardiovascular diseases

(heart attack, cardiomyopathy): blood pressure control, smoking cessation, prevention and treatment of viral diseases - Healthy lifestyle

(no smoking, alcohol) - Taking antiarrhythmic drugs and installing implantable cardioverter defibrillators

Patients with this pathology are observed and treated by cardiologists, arrhythmologists and cardiac surgeons. All these services are available at our New Hospital clinic.

Causes of tachycardia

The causes of increased heart rate are divided into two large groups: cardiac (intracardial), in which the rhythm disturbance occurs due to a problem in the heart, and extracardiac (extracardiac), in which the main problem is outside the heart.

Cardiac causes of tachycardia:

- heart failure;

- myocardial infarction;

- unstable angina;

- anatomical (congenital) heart defects - mitral stenosis, aortic stenosis;

- cardiosclerosis - pathological widespread proliferation of connective tissue in the myocardium;

- cardiomyopathies - a group of diseases in which the heart pathologically expands with thinning or excessive growth of the myocardium;

- inflammatory processes in the heart;

- hypertension - a stable increase in blood pressure;

- anemia is a condition accompanied by a decrease in the level of hemoglobin and red blood cells in the blood;

- hypoxemia - decreased oxygen content in the blood;

- acute vascular insufficiency.

Extracardiac causes:

- heavy physical activity;

- stress;

- pathology of the central or peripheral nervous system;

- mental disorders;

- infectious diseases with fever;

- the effect of medications;

- intoxication with poisons;

- the effects of tobacco, alcohol, coffee and strong tea;

- dehydration, including blood loss;

- pain shock;

- pathology of the endocrine system;

- hypoglycemia - decreased blood glucose levels;

- low blood pressure;

- sedentary lifestyle;

- respiratory failure;

- rapid and significant loss of body weight;

- hypokalemia - decreased potassium levels in the blood;

- injuries.

Tachycardia is not the cause of the disease, but a consequence of another pathology

Treatment and prognosis

In case of sudden attacks of tachycardia, the child should be taken out into the fresh air, tight clothes should be removed, a damp handkerchief should be placed on the forehead, and then a doctor should be called. If there is no pathology, and hormonal changes and stress lead to an acceleration of the heart rate, to treat tachycardia in children, the cardiologist will prescribe drug therapy (beta-blockers, cardiac glycosides, calcium antagonists, sedatives). Auxiliary measures: physical therapy, valgus techniques. To alleviate the condition, a diet is recommended in which it is undesirable to consume chocolate, tea, spicy, and salty foods.

Children who follow the doctor's recommendations usually return to their previous lives and activities. In rare cases, when the disease develops due to other serious pathologies that cannot be treated conservatively, surgery is prescribed.