Aortic valve insufficiency

Aortic valve insufficiency - or aortic regurgitation - is a pathological condition in which the heart's aortic valve leaflets do not close tightly. The valve defect allows blood to flow back from the aorta into the left ventricle.

Backflow prevents the heart from effectively pumping blood to the rest of the body. As a result, you feel tired and short of breath. Aortic valve insufficiency can develop suddenly (acutely) or over a long period of time. Aortic insufficiency has many causes, ranging from congenital heart defects to complications of infectious diseases. Over time, aortic valve insufficiency becomes severe and surgery to replace the aortic valve is required.

Symptoms

Most often, aortic valve regurgitation develops gradually and your heart compensates for the problem. You may not have any signs or symptoms for many years, and you may not even know you have the disease.

However, when aortic valve regurgitation gets worse, the following symptoms appear:

- fatigue and weakness, especially when the level of exercise increases;

- shortness of breath on exertion or at rest;

- chest pain (angina), discomfort and tension, often increasing during exercise;

- increased heart rate (arrhythmia);

- heart murmur;

- rapid heartbeat - sensations of rapid, fluttering pulse;

- swelling of the ankles and feet (edema).

Symptoms

{banner_banstat1}

The thickened aorta does not manifest itself for a long time.

Over time, the lumen of the blood vessels narrows, and the nutrition of the internal organs is disrupted. The clinical picture of the disease is determined by the location of the lesion.

- The narrowing of the coronary vessels, which occurs against the background of hardening of the aorta, is manifested by frequent attacks of angina or the development of myocardial infarction.

- The carotid artery arises from the thoracic aorta and supplies blood to the brain. When cerebral vessels are damaged, patients develop neurological symptoms, their general condition worsens, and the help of a specialist is required.

- Consolidation of the abdominal aorta is manifested by nagging pain in the abdomen, weight loss and symptoms of impaired digestion. In severe cases, signs of peritonitis appear: sharp pain, “acute abdomen,” fever and severe dyspepsia.

- Damage to the vessels supplying blood to the lower extremities leads to characteristic lameness. When walking, patients experience pain and cramps, forcing them to stop.

Causes

Aortic valve regurgitation disrupts the normal flow of blood through your heart and its valves.

Your heart, the center of the cardiovascular system, has four chambers. The two upper chambers, the atria, receive blood. The two lower chambers, the ventricles, pump blood to the lungs and the rest of your body. Blood flows through the chambers of the heart, supported by the four clans of the heart.

The aortic valve is made up of three tight-fitting, triangular pieces of tissue called cusps. These leaflets are attached to the aorta through the so-called ring.

Heart valves open only in one direction. The aortic valve leaflets can only open into the left ventricle and blood is ejected into the aorta. When the blood has passed through the valve and the left ventricle has relaxed, the valves close so that the blood that just passed into the aorta does not flow back into the left ventricle.

A faulty heart valve may not open or close completely. When the valve does not close tightly, blood can leak back. This backflow of blood through the valve is called regurgitation.

Diagnostics

{banner_banstat2}

Aortic thickening is detected by chance, since this pathology is often asymptomatic.

Pathological foci occur in certain areas of the blood vessel or its entire length. There are no specific symptoms of aortic thickening. The doctor can make a preliminary diagnosis based on the patient’s complaints, clinical picture, auscultatory examination data - emphasis of the second tone on the aorta, characteristic murmur. A large difference between blood pressure numbers also indicates involvement of the aorta in the pathological process.

The most reliable diagnostic methods are:

- X-ray examination in direct and lateral projections allows us to examine the shadow of the heart and large blood vessels. In persons with aortic compaction, its shadow is elongated, there is a bend along the vessel and a pathological turn, the aorta is dilated, and the intensity of the shadow is increased.

- Contrast angiography is the most effective diagnostic method.

- Consolidation of the aortic arch is often discovered accidentally during fluorography.

- Ultrasound examination and Dopplerography.

- Magnetic resonance imaging allows you to identify changes in the aorta and determine the degree of circulatory disturbance.

Risk factors

The risk of aortic regurgitation is greater if you are affected by any of the following:

- Damage to the aortic valve.

Inflammation associated with certain conditions, such as endocarditis or rheumatism, can damage your aortic valve. - High blood pressure (hypertension).

High blood pressure makes the heart work harder, increasing stress on the aortic valve, which can make it less elastic and prone to leaking. - Congenital defect of the aortic valve.

If you were born with a unicuspid or bicuspid aortic valve, your chances of aortic regurgitation increase. - Disease.

Certain conditions, including Marfan syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis and syphilis, can cause dilatation of the aortic root (where the aorta attaches to the ventricle), resulting in a leaky aortic valve.

Causes of aortic pathologies

Aortic pathology occurs under the influence of three groups of factors:

- Removable. These include a sedentary lifestyle, alcohol abuse, smoking and eating large amounts of fatty foods.

- Partially removable. Such factors include diabetes mellitus, obesity, chronic intoxication of the body, infectious diseases and arterial hypertension.

- Unremovable. Such factors of aortic pathology include genetic predisposition and age.

Complications

Aortic valve insufficiency—or any heart valve problem—puts you at risk for endocarditis. Endocarditis is an infection of the inner lining of the heart, the endocardium. Typically, this infection affects one of the heart valves, especially if it is already damaged. If the aortic valve is incompetent, it is more susceptible to infection than a healthy valve. You may develop endocarditis when bacteria from another part of your body travels through the bloodstream and travels to your heart.

When aortic valve regurgitation is of moderate severity, it may not pose a serious threat to your health. But when it is severe aortic valve regurgitation, it can lead to heart failure. Heart failure is a serious condition in which your heart is unable to pump enough blood to meet your body's needs.

Diagnostic tests

Common tests to diagnose aortic valve regurgitation include:

- Echocardiogram.

This test uses sound waves to produce an image of your heart. In echocardiography, sound waves are sent to your heart from a wand-like device (transducer) placed on your chest. Sound waves bounce off your heart and are reflected back through your chest wall and processed electronically to provide video images of your heart. An echocardiogram allows your doctor to take a close look at your aortic valve. A certain type of echocardiography, Doppler echocardiography, may be used. This allows measurements of the volume of blood that flows in the opposite direction through the aortic valve. This volume is expressed in cubic centimeters per beat. - Chest X-ray.

Using a chest X-ray, your doctor can examine the shape and size of your heart to determine whether your left ventricle is enlarged, a possible sign of damage to the aortic valve. - Electrocardiogram (ECG).

In this test, wires (electrodes) are attached to your skin to measure electrical impulses from your heart. The pulses are reflected as waves displayed on a monitor or printed on paper. An ECG can provide information about whether the left ventricle is enlarged, a problem that can occur with aortic valve insufficiency. - Transesophageal echocardiography.

This type of echocardiography allows you to take a closer look at your aortic valve. A “sensor tube” is inserted through your esophagus and goes into your stomach and is closer to your heart. In traditional echocardiography, a device called a transducer moves on your chest to produce the sound waves needed to create a picture of your beating heart. In transesophageal echocardiography, a small probe is attached to the end of a tube and passed through the esophagus. This is done to better visualize the image of your aortic valve and the bleeding through it, since the sensor is closer to the valve itself. - Exercises, tests.

Various types of exercise tests to assess activity tolerance and test your heart's response to exercise (sports). - Cardiac catheterization.

Your doctor may order this procedure if noninvasive tests have not provided enough information to firmly diagnose the type and severity of your heart disease. The doctor threads a thin tube (catheter) through a blood vessel in your arm or groin and into your heart. A contrast agent is injected through a catheter in your heart, making details visible on an X-ray. Cardiac catheterization can show if blood is flowing back from the aorta in the heart into the left ventricle. Some catheters are equipped with special sensors that can measure pressure within the chambers of the heart. Pressure may be increased in the left ventricle with aortic valve insufficiency.

ECG

These tests help doctors diagnose aortic valve regurgitation, determine how severe the problem is, and decide whether your aortic valve needs replacement.

Treatments and drugs

Treatment for aortic valve insufficiency depends on how severe the symptoms of the disease are and how the damaged valve affects the functioning of the heart.

Observation

Individuals with mild aortic valve regurgitation do not require treatment. However, even if you do not have signs and symptoms of aortic valve insufficiency, it is worth seeing your doctor regularly. Regular monitoring by a doctor will help to identify the progression of the disease and recommend the correct treatment.

Medicines

Medicines cannot eliminate aortic valve insufficiency. However, there are a number of drugs that help reduce the symptoms of the disease. Control your blood pressure and your weight.

Surgery

As aortic regurgitation progresses, valve replacement surgery may be required. The heart is usually good at fighting problems caused by a leaky aortic valve, the problem is that if the valve is not fixed or replaced in due time, the strength of your heart can decrease so much that it permanently weakens. You can avoid this by having surgery at the appropriate time.

Overall cardiac function and the amount of regurgitation helps determine when surgery is necessary. Surgical procedures include:

- Aortic valve plastic surgery.

Aortic valve repair is performed to preserve the valve and improve its function. Sometimes surgeons can modify the original valve (valvuloplasty) to eliminate the backflow of blood. You will not need long-term drug therapy to prevent blood clots (anticoagulant therapy) after valvuloplasty. - Valve replacement surgery.

In many cases, the aortic valve must be replaced to correct aortic valve regurgitation. Your surgeon removes your aortic valve and replaces it with a mechanical valve or a biologic valve. Mechanical valves, made of metal, are durable, but they carry the risk of blood clots forming on or near the valve. If you have a mechanical aortic valve, you will need to take anticoagulant medications such as warfarin (Coumadin) for life to prevent blood clots. Biological valves, made from pig, cow or human cadaveric donor tissue, often need to be replaced. Sometimes another type of biological valve can be used, which is your own pulmonary artery valve (autograft).

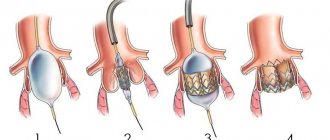

Aortic valve

Traditionally, aortic valve replacement surgery is performed on an open-heart procedure. A less invasive approach is transcatheter aortic valve implantation—installation of a new valve using a catheter through the femoral artery in your leg (transfemoral) or the left ventricle of your heart (transapical). Currently, this procedure is generally limited to those individuals who have aortic valve stenosis or aortic valve regurgitation, and carries a high risk of surgical complications. In the future, transcatheter aortic valve implantation may be an option for the treatment of aortic regurgitation.

Aortic valve insufficiency can be corrected with surgery and you will usually be back to your normal life within a few months. The prognosis after surgery is good.

Aortic valve defects in adults: modern pathology and indications for surgery

S.L. Dzemeshkevich

Dr. honey. Sciences, Professor, Cardiac Surgeon, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, RKNPK

In developed countries, calcified aortic disease is the third most common nosological form after arterial hypertension and coronary heart disease [1].

Knowledge of the etiology of the process that led to aortic disease can significantly influence both surgical tactics and the postoperative treatment protocol for patients and, ultimately, the long-term prognosis. Therefore, at all stages of treatment, one should strive to answer the question of the etiology of the primary process that caused valve dysfunction. Sometimes this answer can only be given by a surgeon who visually assesses the nature of the valve damage already during surgery. In any case, elucidation of the etiology, even with a presumptive conclusion, is extremely important.

Etiology

Assessing our own experience and published data from colleagues from other Russian clinics, it is necessary to emphasize that even today aortic malformations of rheumatic etiology dominate in cardiac surgery hospitals, although not as clearly as in the statistics half a century ago. This figure does not exceed 30-40%. However, if we take into account that only during the period from 1993 to 1998 in Russia the frequency of the cardiac form of rheumatism increased 7 times [2], then in the future we should again expect an increase in the number of patients with rheumatic valve defects.

The increase in surgical interventions on the aortic valve in the group of patients over 60 years of age has significantly increased the number of atherosclerotic “degenerative” (age-related) aortic valve defects. If aortic disease is moderately expressed and combined with widespread atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries, aorta and its branches in combination with distinct specific disorders in lipid metabolism (total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins, triglycerides), then the atherosclerotic origin of the process on the valve is beyond doubt. This is a special and prognostically most severe group of patients. It is to this category of patients that the point of view of some authors extends that aortic stenosis is a special form of manifestation of atherosclerosis with risk factors identical to this systemic disease.

In a real clinical situation, no more than 50% of elderly patients with signs of aortic stenosis have changes in the coronary vessels [3-5]. Such patients have another degenerative process in the valve with a reduced level of metabolic reactions due to age-related changes: atherosclerosis as such can only play the role of an accelerating factor, especially if it is accompanied by inflammatory changes in the aortic valve leaflets, specific to many atheromas, due to the invasion of Chlamydia pneumoniae [6, 7 ]. Age-related involutional calcium degeneration is, in our opinion, the most appropriate definition for this pathology of the aortic valve. As a special form, it is often found in elderly patients and, as a rule, when analyzed, falls into the group of atherosclerotic defects. The diagnostic line between these two groups of patients (atherosclerosis and age-related dystrophy) is very thin, but it is quite possible to draw it with a certain amount of experience. The practical significance of such a diagnosis can be expressed not only in a different prognosis, but also in the amount of drug therapy after surgery (use of antiplatelet agents, lipid-lowering drugs).

The same type of “degenerative” defects with severe calcification includes a group of patients with a congenital bicuspid aortic valve configuration. This was unexpected for us, but the number of such patients increases as the number of elderly patients operated on increases.

Actually, the three main causes of aortic heart defects that we have already noted together account for at least 90% of the causes of aortic valve stenosis [5, 8-13]. All these reasons lead to different pathomorphological, but similar functional changes in the aortic valve leaflets, limiting their mobility. This process (fibrosis, thickening, formation of adhesions in the commissure area, calcification) always takes a long time - years, or even decades. Other, more rare causes of aortic stenosis include previous and active infective endocarditis, systemic lupus erythematosus (verrucous aseptic endocarditis of Libman-Sachs), hereditary metabolic disorders such as homozygous hyperlipoproteinemia type II and alkaptonuria (ochronosis), metastatic calcification of the aortic valve in patients with chronic renal failure [14-16].

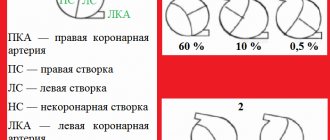

Pure or dominant aortic insufficiency is much less common than stenosis. With combined lesions, the most common cause is rheumatic valvulitis, which leads to wrinkling and shortening of the aortic valve leaflets. Infectious endocarditis plays a significant role, forming aortic insufficiency either on the native valve or by altering the natural history of such anomalies as a bicuspid or prolapsed aortic valve. And yet, despite the fact that rheumatism is the most common cause of aortic insufficiency and in this nosology is not an absolutely dominant process, other causes of aortic insufficiency in the aggregate are much more diverse than with aortic stenosis. All this diversity can be divided into three pathomorphological groups:

• aortic insufficiency with changes only in the semilunar cusps (rheumatism, infective endocarditis, bicuspid valve, cusp prolapse);

• aortic insufficiency as a result of pathology of the ascending aorta with anatomically unchanged leaflets (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, syphilitic aortitis, ankylosing spondylitis, dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta);

• aortic insufficiency with anatomically preserved aorta and aortic cusps (secondary prolapse with a ventricular septal defect, hypertension).

Indications for surgery

The symptom complexes characteristic of a particular valve defect determine modern treatment tactics to a much greater extent than the actual nature of the damage to the aortic valves. Therefore, any attempt to identify a diagnosis of the condition, justify indications for surgical intervention and surgical tactics only on topical diagnostic data (orifice diameter, the amount of valve prolapse, the amount of pressure drop across the valve, the presence or absence of signs of calcification, etc.) does not indicate the benefit of a comprehensive clinical analysis of the condition of a particular patient.

Cardiologists today reliably diagnose this pathology and promptly send such patients to cardiac surgeons. And yet, when deciding on surgery in patients over 70 years of age, we sometimes encounter some resistance from our fellow cardiologists. Their doubts are based on both an objective factor - the higher risk of surgery, and a subjective one - the unknown of the individually “programmed” life expectancy of such elderly patients.

Therefore, in this publication we specifically report data from O'Keefe et al., [17] who were able to follow a group of 50 patients awaiting balloon dilatation of a stenotic aortic valve. The average age of patients exceeded 70 years, survival without surgery by the 3rd year of observation was only 25%. At the same time, in the randomized group of patients without aortic pathology, the survival rate was 77%. Considering that today mortality in aortic replacement is minimal, then these data should convincingly prove to cardiologists the need for surgical treatment of such patients.

In classic situations, the question “when to operate?” does not present any difficulties: digital radiography from the screen of an electron-optical converter, ECG, echocardiography, MRI with contrast are sufficient methods for making a topical diagnosis and assessing the condition of the left ventricle of the heart. Performing sounding of the heart cavities in patients with aortic defects in order to determine the pressure drop, the volume of regurgitation, end-diastolic pressure in the left ventricle or pulmonary capillary wedge pressure today can already be regarded as a diagnostic anachronism.

In our practice, we are naturally especially wary of choosing a solution in patients with “minor” symptoms and, even more so, in asymptomatic patients. It is known that clinical manifestations and complaints may be absent even with severe severe aortic stenosis with an orifice area of less than 0.8 cm3 and with a decrease in the ejection fraction to 25-30% [18].

Enlargement of the left ventricle of the heart to 6 cm or more (in patients with aortic insufficiency), as well as hypertrophy with overload of the left ventricle (in patients with aortic stenosis), are sufficient instrumental criteria for the need for surgery in the presence of a topical diagnosis.

Doppler echocardiography makes it possible to determine the magnitude of the pressure drop with almost the same accuracy as probing of the left ventricle. Understanding the conventions and multifactorial dependence of this indicator, we consider its value to be 40-50 mm Hg. Art. sufficient grounds for a more detailed examination of the patient and search for arguments in favor of surgery.

Calculation of the size of the effective opening is less dependent on the characteristics of blood flow through the section “left ventricle-aortic valve-ascending aorta”, but this indicator is quite conditional and “semi-quantitative”. And yet, we definitely take into account the instructions of ultrasound diagnostic specialists to limit the opening of the valve leaflets to less than 1.5 cm, and when the opening size is less than 1 cm, the indications for surgery are almost absolute. An even more accurate expression of the degree of stenosis is the ratio of the size of the stenosis to the total body surface area - a value of less than 0.6 cm/m2 is critical [19]. If there is information about valve calcification, then you should not postpone the operation, since progression of the process is inevitable.

If the arguments in favor of the operation are not absolute, then for aortic stenosis we calculate the pressure loss across the valve (mm Hg/ml stroke volume) - the value is 1 mm Hg. Art./ml and more significant and weighty. If necessary, repeat these calculations under load. In aortic insufficiency, a decrease in the ejection fraction of less than 55% and its further decrease (or unchanged) under stress test conditions also indicate the limit of compensatory reserves of the left ventricular myocardium and serve as a more than convincing criterion in favor of surgery.

In the presence of concomitant coronary pathology requiring surgical correction, or concomitant mitral valve defects, the criteria for revision and intervention on the aortic valve can be much more liberal and are often determined by the individual decision of the operating surgeon.

It should be remembered that aortic stenosis progresses regardless of any patterns. However, with degenerative defects this process occurs faster than with rheumatic defects or in the presence of a bicuspid valve. With slow progression, the opening of the aortic valve narrows by 0.02 cm2 per year, and with rapid progression - more than 0.3 cm2 per year. When the peak velocity of blood flow through the valve reaches about 4 m/s, the two-year survival rate without surgery is only 21%. Thus, calcification, the rapid progression of stenosis over the course of a year and positive stress tests (a slight increase or even a decrease in blood pressure during exercise) are real factors for deciding on surgery for asymptomatic aortic stenosis.

In asymptomatic aortic insufficiency, the prognosis is based on assessment of left ventricular function and the degree of dilatation of the ascending aorta. Threatening signs are an increase in end-diastolic pressure of the left ventricle more than 70 mm, end-systolic pressure more than 50 mm (index more than 25 mm/m2 of the patient’s body surface), a decrease in the ejection fraction to 50%. If the ascending aorta is dilated more than 55 mm, surgery should be offered regardless of the degree of aortic regurgitation and left ventricular function. In patients with a bicuspid valve or Marfan syndrome, the indications for surgery are even more stringent - the threshold for making a decision is the diameter of the ascending aorta is 50 mm.

Continuous planned monitoring of the condition is necessary for all patients with symptoms of aortic disease and is mandatory every 12 months so as not to miss the time for possible surgical interventions.

Bibliography

1. Jund B. et al. //Eur. Heart J. 2002. V. 23. P. 1253.

2. Diseases of the heart and blood vessels // Pathological anatomy / Ed. Paltse-va M.A., Anichkova N.M. T. 2.Ch. 1. Ch. 11. M., 2001. P. 8.

3. Lindroos M. et al. //J. Amer. Coll. Cardiol. 1993. V. 21. P. 1220.

4. Iivanainen AM et al. // Amer. J. Cardiol. 1996. V. 78. P. 97.

5. Stewart BF et al. //J. Amer. Coll. Cardiol. 1997. V. 29. P. 630.

6. Nystrom-Rosander C et al. // Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1997. V. 29. P. 361.

7. Juvonen J. et al. // J. Amer. Coll. Cardiol. 1997. V. 29. P. 1054.

8. Passik CS et al. // Mayo Clin. Proc. 1987. V. 62. P. 119.

9. Davies MI Butterworths. L., 1980.

10. Subramanian R. et al. // Mayo Clin. Proc. 1984. V. 59. P. 683.

11. Subramanian R. et al. // Mayo Clin. Proc. 1985. V. 60. P. 247.

12. Peterson MD et al. //Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1985. V. 109. P. 829.

13. David TE//J. Heart Valve Dis. 1999. V. 8. P. 495.

14. Roberts WC et al. // Amer. J. Cardiol. 1973. V. 31. P. 557.

15. Roberts WC et al. // Circulation. 1967. V. 36. P. 449.

16. Pritzker MR et al. //Ann. Intern. Med. 1980. V. 93. P. 434.

17. O'Keefe JH et al. // Mayo Clin. Proc. 1987. V. 62. P. 986.

18. Corabello B. // J. Heart Valve Dis. 1995. V. 4. Suppl. 11. P. 132.

19. Rahimtoola SH //J. Amer. Coll. Cardiol. 1989. V. 14. P. 1.

The article was published in Atmosfera magazine. Cardiology

Lifestyle

To improve your quality of life if you have aortic valve regurgitation, your doctor may—in addition to other treatments—may recommend:

- Monitor increases in blood pressure.

Reduces blood pressure, reduces the load on the aortic valve. - Eat less salt.

Reducing your salt intake helps you keep your blood pressure within a normal range, which is very important if you have aortic valve regurgitation. - Visit your dentist regularly.

Follow your care instructions. - Maintain a healthy weight.

Maintain your weight within the range recommended by your doctor. Excess weight puts extra work on your heart. - Exercise.

Perform the exercise as recommended by your doctor. He or she may recommend a program of specific intensity depending on the severity of your aortic valve regurgitation. Exercise alone will not improve your condition, but it can help lower your blood pressure. Exercise also helps maintain overall fitness, which will aid in recovery if you need heart surgery. - Visit your doctor regularly.

Set up a regular schedule for visiting your cardiologist or your primary care physician.

If you are a woman of childbearing age with aortic valve regurgitation, discuss pregnancy and family planning with your doctor because your heart will work harder during pregnancy. How much extra work your heart can do with aortic valve regurgitation depends on the degree of regurgitation and how well your heart contracts. If you become pregnant, you will need care from your cardiologist and obstetrician during pregnancy, labor, and postpartum.

Diagnosis of pathology

Diagnosis of pathology includes:

- Examination of the patient.

- Anamnesis collection.

- Instrumental and laboratory studies.

At the appointment, the doctor will listen to all complaints, assess the patient’s weight, measure blood pressure, identify all risk factors, and identify signs of pathology.

Laboratory tests necessarily include a blood test assessing indicators such as the concentration of lipoproteins, cholesterol and triglycerides.

Instrumental studies include:

- ECG.

- Aortography and angiography. During such an examination, specialists examine the condition of the vessels, identify aneurysms and other lesions.

- Coronagraphy. This examination allows you to assess the condition of the coronary arteries.

- Ultrasound. The examination reveals deterioration in blood flow, decreased lumen of blood vessels, the presence of blood clots and plaques on the walls, and the appearance of aneurysms.

- Rheovasography. This examination allows you to assess the speed of blood flow.

- CT and MRI. These techniques allow you to quickly detect arterial protrusions, localization and extent of damage.