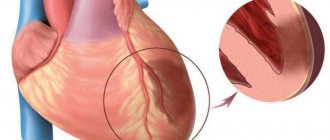

The main and most common cause of myocardial infarction is a violation of blood flow in the coronary arteries, which supply the heart muscle with blood and, accordingly, oxygen. Most often, this disorder occurs against the background of atherosclerosis of the arteries, in which atherosclerotic plaques form on the walls of blood vessels. These plaques narrow the lumen of the coronary arteries and can also contribute to the destruction of vessel walls, which creates additional conditions for the formation of blood clots and arterial stenosis.

Risk factors for myocardial infarction

The main risk factor for myocardial infarction is atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries.

There are a number of factors that significantly increase the risk of developing this acute condition:

- Atherosclerosis. A disorder of lipid metabolism, in which the formation of atherosclerotic plaques on the walls of blood vessels occurs, is the main risk factor in the development of myocardial infarction.

- Age. The risk of developing the disease increases after 45–50 years of age.

- Floor. According to statistics, this acute condition occurs 1.5–2 times more often in women than in men; the risk of developing myocardial infarction is especially high in women during menopause.

- Arterial hypertension. People suffering from hypertension have an increased risk of cardiovascular accidents, since elevated blood pressure increases the myocardial oxygen demand.

- Previous myocardial infarction, even small focal ones.

- Smoking. This harmful habit leads to disruption of the functioning of many organs and systems of our body. With chronic nicotine intoxication, the coronary arteries narrow, which leads to insufficient oxygen supply to the myocardium. Moreover, we are talking not only about active smoking, but also passive smoking.

- Obesity and physical inactivity. If fat metabolism is disrupted, the development of atherosclerosis and arterial hypertension accelerates, and the risk of diabetes mellitus increases. Insufficient physical activity also negatively affects the body's metabolism, being one of the reasons for the accumulation of excess body weight.

- Diabetes. Patients suffering from diabetes have a high risk of developing myocardial infarction, since elevated blood glucose levels have a detrimental effect on the walls of blood vessels and hemoglobin, impairing its transport function (oxygen transfer).

Symptoms of myocardial infarction

This acute condition has quite specific symptoms, and they are usually so pronounced that they cannot go unnoticed. However, it should be remembered that atypical forms of this disease also occur.

In the vast majority of cases, patients experience a typical painful form of myocardial infarction, thanks to which the doctor has the opportunity to correctly diagnose the disease and immediately begin its treatment.

The main symptom of the disease is severe pain. The pain that occurs during myocardial infarction is localized behind the sternum, it is burning, dagger-like, and some patients characterize it as “tearing.” The pain can radiate to the left arm, lower jaw, and interscapular area. The occurrence of this symptom is not always preceded by physical activity; pain often occurs at rest or at night. The described characteristics of the pain syndrome are similar to those during an attack of angina, however, they have clear differences.

Unlike an attack of angina, pain during myocardial infarction persists for more than 30 minutes and is not relieved by rest or repeated administration of nitroglycerin. It should be noted that even in cases where a painful attack lasts more than 15 minutes, and the measures taken are ineffective, it is necessary to immediately call an ambulance team.

Atypical forms of myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction occurring in an atypical form can cause difficulties for a doctor when making a diagnosis.

Gastritis variant. The pain syndrome that occurs with this form of the disease resembles pain during exacerbation of gastritis and is localized in the epigastric region. On examination, tension in the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall may be observed. Typically, this form of myocardial infarction occurs when the lower parts of the left ventricle, which are adjacent to the diaphragm, are affected.

Asthmatic variant. Reminds me of a severe attack of bronchial asthma. The patient experiences suffocation, cough with foamy sputum (but can also be dry), while the typical pain syndrome is absent or mildly expressed. In severe cases, pulmonary edema may develop. Upon examination, cardiac arrhythmias, decreased blood pressure, and wheezing in the lungs may be detected. Most often, the asthmatic form of the disease occurs with repeated myocardial infarctions, as well as against the background of severe cardiosclerosis.

Arrhythmic option. This form of myocardial infarction manifests itself in the form of various arrhythmias (extrasystole, atrial fibrillation or paroxysmal tachycardia) or atrioventricular block of varying degrees. Due to heart rhythm disturbances, the picture of myocardial infarction on the electrocardiogram may be masked.

Cerebral option. Characterized by impaired blood circulation in the vessels of the brain. Patients may complain of dizziness, headache, nausea and vomiting, weakness in the limbs, and consciousness may be confused.

Painless option (erased form). This form of myocardial infarction causes the greatest difficulties in diagnosis. Pain syndrome may be completely absent; patients complain of vague chest discomfort and increased sweating. Most often, this erased form of the disease develops in patients with diabetes and is very difficult.

Sometimes the clinical picture of myocardial infarction may contain symptoms of different variants of the disease; the prognosis in such cases, unfortunately, is unfavorable.

Modern approaches to the treatment of acute myocardial infarction

Today, myocardial infarction (MI) remains as serious a disease as it was several decades ago.

Here is just one example that proves the severity of this disease: about 50% of patients die before they have time to meet with a doctor.

At the same time, it is clear that the risk of MI for life and health has become significantly lower. After the basic principles of intensive care wards for coronary patients were developed 35 years ago and these wards began to actually work in healthcare practice, the effectiveness of treatment and prevention of cardiac arrhythmias and conduction disorders in patients with myocardial infarction significantly increased and hospital mortality decreased. In the 70s, it was more than 20%, but in the last 15 years, after the role of thrombosis in the pathogenesis of acute MI was proven and the beneficial effect of thrombolytic therapy was shown, in a number of clinics the mortality rate has decreased by 2 times or more.

It must be said that the basic principles and recommendations for the treatment of acute MI, however, as for most other serious pathologies, are based not only on the experience and knowledge of individual clinics, areas, schools, but also on the results of large multicenter studies, sometimes carried out simultaneously in many hundreds of hospitals around the world. Of course, this allows the doctor to quickly find the right solution in standard clinical situations.

The main objectives of treatment of acute MI can be called the following: relief of a painful attack, limiting the size of the primary focus of myocardial damage and, finally, prevention and treatment of complications. A typical anginal attack, which develops in the vast majority of patients with MI, is associated with myocardial ischemia and continues until necrosis occurs of those cardiomyocytes that should die.

One of the proofs of precisely this origin of pain is its rapid disappearance when coronary blood flow is restored (for example, against the background of thrombolytic therapy).

Relieving a pain attack

Pain itself, acting on the sympathetic nervous system, can significantly increase heart rate, blood pressure (BP), and heart function. It is these factors that determine the need to stop a painful attack as quickly as possible. It is advisable to give the patient nitroglycerin under the tongue.

This may relieve pain if the patient has not previously received nitroglycerin for this attack. Nitroglycerin can be in tablet or aerosol form. There is no need to resort to its use if systolic blood pressure is below 90 mm Hg.

Morphine is used all over the world to relieve pain.

which is administered intravenously in fractional doses from 2 to 5 mg every 5–30 minutes as needed until complete (if possible) pain relief.

The maximum dose is 2–3 mg per 1 kg of patient body weight. Intramuscular administration of morphine should be avoided, since the result in this case is unpredictable.

Side effects are extremely rare (mainly hypotension, bradycardia) and are quite easily controlled by elevating the legs, administering atropine, and sometimes plasma replacement fluid.

In elderly people, depression of the respiratory center is uncommon, so morphine should be administered in a reduced (even half) dose and with caution. The antagonist of morphine is naloxone

, which is also administered intravenously, it relieves all side effects, including respiratory depression caused by opiates.

The use of other narcotic analgesics, for example promedol and other drugs of this series, is not excluded. The suggestion that neuroleptanalgesia (a combination of fentanyl and droperidol) has a number of benefits has not been clinically confirmed. Attempts to replace morphine with a combination of non-narcotic analgesics and antipsychotics in this situation are unjustified. Thrombolytic therapy

The main pathogenetic method of treating MI is to restore the patency of the occluded coronary artery. Most often, to achieve this, either thrombolytic therapy or mechanical destruction of the thrombus is used during transluminal coronary angioplasty. For most clinics in our country, the most realistic option today is to use the first method.

The process of necrosis develops extremely quickly in humans and generally ends, as a rule, within 6–12 hours from the onset of an anginal attack, therefore, the faster and more fully it is possible to restore blood flow through the thrombosed artery, the more preserved will be the functional ability of the left ventricular myocardium and ultimately resulting in less mortality. It is considered optimal to start administering thrombolytic drugs 2–4 hours after the onset of the disease.

The success of treatment will be greater if it is possible to reduce the period of time before the start of thrombolytic therapy, which can be done in two ways: the first is early detection and hospitalization of patients in the hospital and rapid decision-making on appropriate treatment, the second is the start of therapy at the prehospital stage.

Our studies have shown that starting thrombolytic therapy at the prehospital stage allows for a gain in time, on average about 2.5 hours.

This method of thrombolytic therapy, if carried out by doctors of a specialized cardiac care team, is relatively safe.

In the absence of contraindications, thrombolytic therapy is advisable for all patients in the first 12 hours of illness. The effectiveness of thrombolytic therapy is higher (42–47% reduction in mortality) if it is started within 1 hour of illness. For periods longer than 12 hours, the use of thrombolytic drugs is problematic and should be decided taking into account the real clinical situation.

Thrombolytic therapy is especially indicated for elderly people, patients with anterior MI, and also in cases where it is started early enough.

A prerequisite for starting thrombolytic therapy is the presence of ST segment elevations on the ECG or signs of bundle branch block.

Thrombolytic therapy is not indicated if

ST

, regardless of how the final phase

of the QRS

on the ECG looks - depressed, negative

T-waves

, or the absence of any changes.

Early initiation of thrombolytic therapy can save up to 30 patients out of 1000 treated.

Today, the main route of administration of thrombolytic drugs is intravenous. All drugs used, first generation thrombolytics

, such as streptokinase (1,500,000 units for 1 hour) - urokinase (3,000,000 units for 1 hour),

second generation

- tissue plasminogen activator (100 mg bolus plus infusion), prourokinase (80 mg bolus plus infusion 1 hour ) – are highly effective thrombolytics.

The risk of thrombolytic therapy is well known - this is the occurrence of bleeding, the most dangerous being cerebral hemorrhage.

The frequency of hemorrhagic complications is low, for example, the number of strokes when using streptokinase does not exceed 0.5%, and when using tissue plasminogen activator - 0.7–0.8%.

As a rule, in case of serious hemorrhages, fresh frozen plasma is administered

and, of course, the administration of the thrombolytic is stopped.

Streptokinase can cause allergic reactions

, which, as a rule, can be prevented by prophylactic administration of corticosteroids - prednisolone or hydrocortisone.

Another complication is hypotension

, which is more often observed when using drugs based on streptokinase; it is often accompanied by bradycardia.

Usually this complication can be stopped after stopping the thrombolytic infusion and administering atropine and adrenaline; sometimes the use of plasma expanders and inotropes is required. Today, suspected aortic dissection, active bleeding, and previous hemorrhagic stroke are considered absolute contraindications to thrombolytic therapy.

On average, only one third of patients with MI receive thrombolytic drugs, and in our country this figure is significantly lower.

Thrombolytics are not administered mainly due to the late admission of patients, the presence of contraindications, or the uncertainty of changes on the ECG. Mortality among patients not receiving thrombolytics remains high and ranges from 15 to 30%. β-blockers

On the 1st day after MI, sympathetic activity increases, therefore the use of β-blockers

, which reduce oxygen consumption by the myocardium, reduce heart function and ventricular wall tension, became the rationale for their use in this category of patients.

A number of large multicenter studies that examined the effectiveness of intravenous b-blockers on the 1st day of MI showed that they reduce mortality in the 1st week by approximately 13–15%. The effect is somewhat higher if treatment begins in the first hours of the disease, and is absent if these drugs are used from the 2-3rd day of the disease. b-blockers also reduce the number of recurrent heart attacks by an average of 15–18%. The mechanism by which b-blockers influence mortality is a reduction in the incidence of ventricular fibrillation and cardiac rupture.

Treatment with b-blockers begins with intravenous administration (metoprolol, atenolol, propranolol) - 2-3 times or as long as necessary to optimally reduce the heart rate. Subsequently, they switch to taking drugs orally: metoprolol 50 mg every 6 hours in the first 2 days, atenolol 50 mg every 12 hours during the day, and then select the dose individually for each patient. The main indications for the use of b-blockers are signs of sympathetic hyperactivity, such as tachycardia in the absence of signs of heart failure, hypertension, pain, and the presence of myocardial ischemia.

b-Blockers, despite the presence of contraindications to their use, for example, bradycardia (heart rate less than 50 per minute), hypotension (systolic blood pressure below 100 mm Hg), the presence of heart block and pulmonary edema, as well as bronchospasm, are used nevertheless, in the overwhelming majority of patients with MI.

However, the ability of drugs to reduce mortality does not extend to the group of b-blockers with their own sympathomimetic activity. If the patient has begun treatment with b-blockers, the drug should be continued until serious contraindications appear. Use of antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants

antiplatelet in acute MI

, in particular

acetylsalicylic acid

, helps reduce thrombosis, and the maximum effect of the drug is achieved quite quickly after taking an initial dose of 300 mg and is stably maintained with daily intake of acetylsalicylic acid in small doses - from 100 to 250 mg / day.

In studies conducted on many thousands of patients, it was found that the use of acetylsalicylic acid reduces 35-day mortality by 23%. Acetylsalicylic acid is contraindicated in case of exacerbation of peptic ulcer disease, with its intolerance, as well as with bronchial asthma provoked by this drug.

Long-term use of the drug significantly reduces the frequency of recurrent heart attacks - up to 25%, so taking acetylsalicylic acid is recommended for an indefinite period.

Another group of drugs that affect platelets are platelet glycoprotein IIB/IIIA blockers. Currently, the effectiveness of the use of two representatives of this class is known and proven - abciximab

and

tiropheban

.

According to the mechanism of action, these drugs compare favorably with acetylsalicylic acid, since they block most of the known pathways of platelet activation. The drugs prevent the formation of a primary platelet thrombus, and their effect is sometimes quite long - up to six months. Worldwide experience is still limited; in our country, work with these drugs is just beginning. heparin

is still widely used , which is mainly prescribed for the prevention of recurrent heart attacks, to prevent thrombosis and thromboembolism. Schemes and doses of its administration are well known. The dose is selected so that the partial thromboplastin time increases by 2 times compared to the norm. The average dose is 1000 IU/hour for 2–3 days; subcutaneous administration of heparin is recommended when patients are slowly mobilized.

Currently there is evidence on the use of low molecular weight heparins

, in particular

enoxyparin

and

fragmin.

Their main advantages are that they actually do not require laboratory monitoring of blood clotting parameters and special equipment, such as infusion pumps, for their administration, and most importantly, they are significantly more effective than unfractionated heparins.

The use of indirect anticoagulants has not lost its importance, especially in cases of venous thrombosis, severe heart failure, and the presence of a blood clot in the left ventricle. Calcium antagonists

Calcium are used as standard therapy for MI

at present, they are actually not used, since they do not have a beneficial effect on the prognosis, and their use from a scientific point of view is unfounded.

Nitrates

Intravenous administration of nitrates during MI in the first 12 hours of the disease reduces the size of the necrosis focus and affects the main complications of MI, including deaths and the incidence of cardiogenic shock.

Their use reduces mortality to 30% in the first 7 days of illness, this is most obvious in anterior localization of infarctions.

Taking nitrates orally starting from the 1st day of the disease does not lead to either an improvement or a worsening of the prognosis by the 30th day of the disease. Intravenous nitrates should be standard therapy for all patients admitted in the early hours of illness with anterior MI and systolic blood pressure greater than 100 mm Hg. Introduce nitroglycerin at a low rate, for example 5 mcg/min, and gradually increase it, achieving a decrease in systolic pressure by 15 mmHg. In patients with arterial hypertension, blood pressure can be reduced to 130–140 mmHg. As a rule, nitrate therapy is carried out within 24 hours unless there is a need to continue this therapy, in particular if pain associated with myocardial ischemia persists or signs of heart failure. ACE inhibitors

angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitors have firmly taken their place in the treatment of patients with MI .

This is primarily determined by the fact that these drugs are able to stop the expansion, dilatation of the left ventricle, and thinning of the myocardium, i.e.

influence the processes leading to remodeling of the left ventricular myocardium and accompanied by a serious deterioration in myocardial contractile function and prognosis. As a rule, treatment with ACE inhibitors begins 24–48 hours after the onset of myocardial infarction to reduce the likelihood of arterial hypertension.

Depending on the initially impaired left ventricular function, therapy can last from several months to many years. It was found that treatment with captopril

at a dose of 150 mg/day in patients without clinical signs of circulatory failure, but with an ejection fraction below 40%, significantly improved the prognosis.

In the treated group, mortality was 19% lower, and there were 22% fewer cases of heart failure requiring hospital treatment. Thus, ACEs (captopril 150 mg/day, ramipril 10 mg/day, lisinopril 10 mg/day, etc.)

are advisable to prescribe to most patients with MI, regardless of its location and the presence or absence of heart failure.

However, this therapy is more effective when clinical signs of heart failure and instrumental studies (low ejection fraction) are combined.

In this case, the risk of death is reduced by 27%, i.e. this prevents deaths in every 40 out of 1000 patients treated during the year.

Already during the patient’s stay in the hospital, it is advisable to study his lipid spectrum in detail.

Acute MI itself somewhat reduces the content of free cholesterol in the blood.

If there is data on significant changes in this indicator, for example, when the level of total cholesterol is above 5.5 mmol/l, it is advisable to recommend the patient not only a lipid-lowering diet, but also taking medications, primarily statins.

Thus, currently the doctor has a significant arsenal of tools to help a patient with MI and minimize the risk of complications.

Of course, the main way to achieve this goal is the use of thrombolytic drugs, but at the same time, the use of b-blockers, aspirin, ACE and nitrates can significantly affect the prognosis and outcome of the disease. Enalapril: Ednit

(Gedeon Richter)

Enap

(KRKA)

| Applications to the article |

| The main objectives of the treatment of acute myocardial infarction: 1) relief of a painful attack 2) limiting the size of the primary myocardial lesion 3) prevention and treatment of complications |

| In the absence of contraindications, thrombolytic therapy is advisable for all patients in the first 12 hours of illness. |

| Intravenous nitrates should be therapy for all patients with anterior myocardial infarction and systolic blood pressure greater than 100 mm Hg. |

| TREATMENT SCHEME FOR ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION |