Some patients develop Takotsubo syndrome due to COVID-19, scientists report. This pathology, romantically called “broken heart syndrome,” feels similar to acute myocardial infarction. However, unlike it, it is completely reversible. Most often, takotsubo occurs in women over 55 years of age, although isolated cases have also been described among men. According to doctors, with COVID-19, the development of the syndrome may be associated with stress and the release of adrenaline into the blood, as well as an inflammatory response to the infection. In addition, the cause may be blood clotting disorders, which are common in coronavirus patients. Experts say takotsubo can greatly worsen the prognosis of those infected, so it needs to be diagnosed early.

Women's share

A team of scientists, which included specialists from the Department of Cardiology of the University of Magna Graecia in Catanzaro (Italy), the Cardiovascular Clinic of the University of Genoa (Italy), the Center for Congenital Heart Diseases for Adults and the Pulmonary Hypertension Center of the Royal Brompton Hospital (UK) published a scientific article , which examined in detail the impact of the new coronavirus on the health of women, children and adolescents.

The study authors emphasize that there are special risks for certain groups of the population, such as older women.

Insidious pathogen

Photo: Depositphotos

“Isolated cases of takotsubo syndrome, caused by severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), have been described in women,” the study said. A team of scientists comes to the conclusion that the disease is associated with the release of adrenaline into the blood and an inflammatory response to infection. The direct effect of SARS-CoV-2 on blood vessels, which provokes left ventricular dysfunction, could also contribute.

Izvestia Help

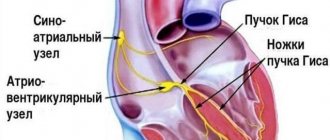

Takotsubo syndrome (TS, broken heart syndrome, stress cardiomyopathy) is a pathology of the heart in which its apex expands. At the same time, spontaneous increased movements of the left ventricle are observed. The patient feels it like an acute heart attack. The syndrome was discovered by Japanese scientists in 1990, and even then it was noted that it often develops against a background of stress due to the loss of loved ones. The main difference from myocardial infarction is that TS is reversible. However, during the acute stage, a significant number of patients develop serious complications: arrhythmia, heart failure, pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock, thromboembolism, cardiac arrest and rupture. It develops mainly in postmenopausal women, but in rare cases it is also observed in men.

Vitamin course: B12 blocks the reproduction of the new coronavirus

This substance disrupts the copying mechanism of SARS-Cov-2

So far, not many cases of the disease have been described in the scientific literature, but scientists emphasize that as the pandemic progresses, the number of such diagnoses may increase. The first clinical case of broken heart syndrome due to COVID-19 was described in the United States by scientists from the Department of Cardiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. A 58-year-old woman was hospitalized with symptoms of coronavirus infection. She subsequently developed mixed shock and an echocardiogram showed hypokinesis (spontaneous movements) of the left ventricle. The patient was cured without serious consequences. Doctors conclude that COVID-19 can contribute to the development of stress cardiomyopathy, but most patients recover fully with adequate treatment.

Forecast

Reperfusion syndrome: causes, symptoms, treatment and prevention

Despite the dire initial clinical presentation in some patients, most patients survive the initial attack with very low rates of in-hospital mortality or complications. After undergoing the acute stage of the disease, patients can expect a favorable outcome with a good long-term prognosis.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Vdqvjh4gfgE

Even with severe systolic dysfunction at the onset of the disease, myocardial contractility begins to recover within the first few days and normalizes within several months. In 5% of cases there is a relapse of the disease, probably provoked by an associated trigger.

Double punch

In combination with coronavirus, this pathology can aggravate the mutual destructive effect on the body, Galina Reva, professor of the department of fundamental medicine at the School of Biomedicine of the Far Eastern Federal University (the university is a participant in the project to increase the competitiveness of education “5-100”), told Izvestia.

— The general toxic effect combines this syndrome with coronavirus. In takotsubo, catecholamines (neurotransmitters and hormones, including adrenaline - Izvestia) play a role; in COVID-19, they are products of metabolic changes caused by virus toxins. The release of these substances doubly aggravates the patient’s condition,” the expert explained.

Insidious pathogen

Photo: Depositphotos

Complete disorder: mental disorders increase the risk of severe COVID-19

Scientists have recognized depression and increased anxiety as the most dangerous conditions during infection.

According to Galina Reva, these diseases themselves have serious differences: Takotsubo is curable, and SARS-CoV-2, according to available data, causes irreversible death of cardiomyocytes. However, if they occur simultaneously, the clinical course will be even more severe and the prognosis will be more unfavorable.

Patients with cardiac pathology that has developed against the background of coronavirus may also encounter difficulties in diagnosis, Philip Kopylov, a professor at the Department of Preventive and Emergency Cardiology at Sechenov University, told Izvestia.

“Today, it is extremely rare for hospitals to undertake coronary angiography (a study of the condition of the coronary vascular bed, which is performed through a puncture of the femoral or radial artery. - Izvestia”), the specialist explained. - And this is necessary to check the condition of the heart. Moreover, I think that not all hospitals where patients with coronavirus are admitted have a high-quality echocardiogram.

Face-to-face insert: where does the human gene fragment come from in SARS-CoV-2?

The new coronavirus could cross the species barrier back in 2012

Notes

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Tsuchuhashi K et al. JACC 2001

- ↑ Kawai et al. JPJ 2000

- ↑ Desmet et al. Heart 2003

- Abe et al. JACC 2003

- ↑

- ↑ Eshtehardi P, Koestner SC, Adorjan P, Windecker S, Meier B, Hess OM, Wahl A, Cook S (July 2009). “Transient apical ballooning syndrome—clinical characteristics, ballooning pattern, and long-term follow-up in a Swiss population.” Int.

J. Cardiol .

135

(3): 370–5. PMID. - Bybee KA, Motiei A, Syed IS, Kara T, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Murphy JG, Hammill SC, Rihal CS, Wright RS (2006). “Electrocardiography cannot reliably differentiate transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome from anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.” J Electrocardiol

. PMID. - ↑ Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR (March 2008). “Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: A systematic review.” Int.

J. Cardiol .

124

(3): 283–92. PMID. - ↑ Shimizu M, Kato Y, Masai H, Shima T, Miwa Y (August 2006). “Recurrent episodes of takotsubo-like transient left ventricular ballooning occurring in different regions: a case report.” J. Cardiol

.

48

(2): 101–7. PMID. - Hurst RT, Askew JW, Reuss CS, Lee RW, Sweeney JP, Fortuin FD, Oh JK, Tajik AJ (August 2006). “Transient midventricular ballooning syndrome: a new variant.” J. Am.

Coll. Cardiol .

48

(3): 579–83. PMID. - Yasu T, Tone K, Kubo N, Saito M (June 2006). “Transient mid-ventricular ballooning cardiomyopathy: a new entity of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.” Int.

J. Cardiol .

110

(1):100–1. PMID. - Dhar S, Koul D, Subramanian S, Bakhshi M (2007). “Transient apical ballooning: sheep in wolves' garb.” Cardiol.

Rev. _

15

(3): 150—3. PMID. - ↑ A. John Camm, Thomas F. Luscher, Patrick Serruys.

The ESC Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. - Wiley-Blackwell, 2006. - 1136 p.

Notes

- ↑Eshtehardi P, Koestner SC, Adorjan P, Windecker S, Meier B, Hess OM, Wahl A, Cook S (July 2009). "Transient apical ballooning syndrome—clinical characteristics, ballooning pattern, and long-term follow-up in a Swiss population." Int. J Cardiol 135(3):370–5. PMID 18599137.

- ↑Mayo Clinic Research Reveals 'broken Heart Syndrome' Recurs in 1 Of 10 Patients

- ↑Akashi YJ, Nef HM, Mollmann, H, Ueyama T (2010). "Stress Cardiomyopathy". Annual Review of Medicine61: 271–86. DOI:10.1146/annurev.med.041908.191750.

- ↑ 12Gianni, M; Dentali F, Grandi AM et al. (December 2006). "Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review." European Heart Journal (Oxford University Press) 27 (13): 1523–1529. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032. PMID 16720686. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ↑ 123Azzarelli S, Galassi AR, Amico F, Giacoppo M, Argentino V, Tomasello SD, Tamburino C, Fiscella A. (2006). "Clinical features of transient left ventricular apical ballooning." Am J Cardiol.98(9):1273–6. DOI:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.065. PMID 17056345.

- ↑Ibáñez B, Navarro F, Farré J, et al. (2004). "" (Spanish; Castilian). Revista española de cardiología57 (3): 209–16. DOI:10.1016/S1885-5857(06)60138-2. PMID 15056424.

- ↑Inoue, M; Shimizu M, Ino H et al. (2005). "Differentiation between patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy and those with anterior acute myocardial infarction." Circ. J.69(1):89–94. DOI:10.1253/circj.69.89. PMID 15635210.

- ↑Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T et al. (2002). "Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation: a novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction." American Heart Journal143(3):448–55. DOI:10.1067/mhj.2002.120403. PMID 11868050.

- ↑ 12Tsuchuhashi K et al. JACC 2001

- ↑ 12Kawai et al. JPJ 2000

- ↑ 12Desmet et al. Heart 2003

- ↑Abe et al. JACC 2003

- ↑Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. (February 2005). "Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress." N.Engl. J Med 352(6):539–48. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa043046. PMID 15703419.

- ↑ 12Elesber, A.A. (July 2007). "Four-Year Recurrence Rate and Prognosis of the Apical Ballooning Syndrome". J Amer Coll Card50(5):448–52. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.050.

- ↑ 1234567 Eshtehardi P, Koestner SC, Adorjan P, Windecker S, Meier B, Hess OM, Wahl A, Cook S (July 2009). "Transient apical ballooning syndrome—clinical characteristics, ballooning pattern, and long-term follow-up in a Swiss population." Int. J Cardiol 135(3):370–5. PMID 18599137.

- ↑Bybee KA, Motiei A, Syed IS, Kara T, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Murphy JG, Hammill SC, Rihal CS, Wright RS (2006). "Electrocardiography cannot reliably differentiate transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome from anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction." J Electrocardiol. PMID 17067626.

- ↑ 12Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR (March 2008). "Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: A systematic review." Int. J Cardiol 124(3):283–92. PMID 17651841.

- ↑ 12Shimizu M, Kato Y, Masai H, Shima T, Miwa Y (August 2006). "Recurrent episodes of takotsubo-like transient left ventricular ballooning occurring in different regions: a case report." J Cardiol 48(2):101–7. PMID 16948453.

- ↑Hurst RT, Askew JW, Reuss CS, Lee RW, Sweeney JP, Fortuin FD, Oh JK, Tajik AJ (August 2006). "Transient midventricular ballooning syndrome: a new variant." J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.48(3):579–83. PMID 16875987.

- ↑Yasu T, Tone K, Kubo N, Saito M (June 2006). "Transient mid-ventricular ballooning cardiomyopathy: a new entity of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy." Int. J Cardiol 110(1):100–1. PMID 15996774.

- ↑Dhar S, Koul D, Subramanian S, Bakhshi M (2007). "Transient apical ballooning: sheep in wolves' garb." Cardiol. Rev.15(3):150–3. PMID 17438381.

- ↑Medics can 'mend a broken heart'

- ↑ 12A. John Camm, Thomas F. Luscher, Patrick Serruys The ESC Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. - Wiley-Blackwell, 2006. - 1136 p.

- ↑Akashi YJ, Nakazawa K, Sakakibara M, Miyake F, Koike H, Sasaka K. (2003). "The clinical features of takotsubo cardiomyopathy". QJM96(8):563–73. DOI:10.1093/qjmed/hcg096. PMID 12897341.

- ↑Nyui N, Yamanaka O, Nakayama R, Sawano M, Kawai S. (2000). "'Tako-Tsubo' transient ventricular dysfunction: a case report." Jpn Circ J64(9):715–9. DOI:10.1253/jcj.64.715. PMID 10981859.

Hans Selye's theory of adaptation to stress

What is stress? This is a set of normal reactions of the body that occur in response to the action of unfavorable factors. War, famine, epidemic, car accident, marriage, birth of a child - all this can become stressful.

The regulation of metabolism, physiological reactions, and behavior is carried out by a chain of hypothalamus, pituitary gland and adrenal glands. Corticotropic hormone of the hypothalamus stimulates the production of adrenocorticotropic hormone of the pituitary gland, which in turn triggers the secretion of cortisol.

Cortisol is a steroid hormone. It is synthesized in the adrenal cortex. Cortisol inhibits the breakdown of glycogen in muscles, activates it in the liver, and takes part in the development of the body's response to stress. How does he work? This hormone stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, giving impetus to any activity.

The concentration of cortisol in the blood changes throughout the day: it is maximum in the morning, when you need to get up and start doing something, and gradually falls during the day. In the evening, the level of the hormone in the blood is low, a person can relax and fall asleep. If he is busy with something important and interesting, then the adrenal glands secrete more cortisol than during routine activities.

What happens under stress? Cortisol levels increase. The hormone tells the body: “fight or flight.” The pulse quickens, blood pressure rises, muscles tense - the person is preparing for immediate decisive action.

This mechanism of adaptation to stress was discovered back in 1936. The author of the theory, biochemist Hans Selye described in detail how the body reacts to any strong stimulus, and introduced the concepts of eustress and distress. In the first case, the body is mobilized to complete the task, the person feels cheerful, active, and productive. And when the situation returns to normal, cortisol levels decrease. A person can “exhale and relax.”

Distress is chronic stress in which cortisol concentrations remain high. A person does not have time to recover and spends all the body’s resources on maintaining combat readiness. Everyday problems do not require “putting out fires and stopping horses in a gallop,” but they constantly keep you at a “low start,” preventing you from relaxing or reacting with your body to relieve tension. Cortisol levels are still high, and the circadian rhythms of its secretion are disrupted. So a person begins to sleep worse at night, body weight increases, blood pressure rises, and the ratio of cholesterol fractions changes.

Selye's triad, which describes this condition, includes 3 groups of symptoms:

- stomach ulcer;

- hypertrophy of the adrenal cortex

- atrophy of the thymus gland (thymus).

“If stress is excessive, it can lead to hypertension, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome,” says Ernesto Shiffrin, a professor in the Faculty of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal.

Notes

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Tsuchuhashi K et al. JACC 2001

- ↑ Kawai et al. JPJ 2000

- ↑ Desmet et al. Heart 2003

- Abe et al. JACC 2003

- ↑

- ↑ Eshtehardi P, Koestner SC, Adorjan P, Windecker S, Meier B, Hess OM, Wahl A, Cook S (July 2009). “Transient apical ballooning syndrome—clinical characteristics, ballooning pattern, and long-term follow-up in a Swiss population.” Int.

J. Cardiol .

135

(3): 370–5. PMID. - Bybee KA, Motiei A, Syed IS, Kara T, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Murphy JG, Hammill SC, Rihal CS, Wright RS (2006). “Electrocardiography cannot reliably differentiate transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome from anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.” J Electrocardiol

. PMID. - ↑ Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR (March 2008). “Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: A systematic review.” Int.

J. Cardiol .

124

(3): 283–92. PMID. - ↑ Shimizu M, Kato Y, Masai H, Shima T, Miwa Y (August 2006). “Recurrent episodes of takotsubo-like transient left ventricular ballooning occurring in different regions: a case report.” J. Cardiol

.

48

(2): 101–7. PMID. - Hurst RT, Askew JW, Reuss CS, Lee RW, Sweeney JP, Fortuin FD, Oh JK, Tajik AJ (August 2006). “Transient midventricular ballooning syndrome: a new variant.” J. Am.

Coll. Cardiol .

48

(3): 579–83. PMID. - Yasu T, Tone K, Kubo N, Saito M (June 2006). “Transient mid-ventricular ballooning cardiomyopathy: a new entity of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.” Int.

J. Cardiol .

110

(1):100–1. PMID. - Dhar S, Koul D, Subramanian S, Bakhshi M (2007). “Transient apical ballooning: sheep in wolves' garb.” Cardiol.

Rev. _

15

(3): 150—3. PMID. - ↑ A. John Camm, Thomas F. Luscher, Patrick Serruys.

The ESC Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. - Wiley-Blackwell, 2006. - 1136 p.

Stressors: Holmes and Ray model

“What will happen to him! Look how he holds up!” - this can be said about any unfamiliar person, and then you are surprised to find out that he is trying his best and has already suffered 2 heart attacks. Based on the time of action, psychogenic factors of CVD are divided into mental trauma and psychotraumatic situations. Injuries occur suddenly, a person is at the mercy of emotions and often does not have time to adapt (acute stress). Psychotraumatic situations exist for a long time, sometimes for years. At some stage, a person can adapt to them, but over time, compensatory mechanisms are exhausted. The disease develops.

How can you assess the strength of the negative influence and the body’s resource? According to the importance of the operating factor, life situations are assigned different numbers of points. In 1970, American psychiatrists T. Holmes and R. Ray analyzed people's reactions to significant events, ranked them and compiled a scale of stressors. The list includes not only obvious disasters, but also a large number of “ordinary” events and situations. The ten most important situations are listed below in descending order:

- death of a spouse or other closest person;

- divorce of spouses;

- separation of spouses (in marriage);

- imprisonment;

- death of one close family member;

- illness (injury);

- marriage;

- dismissal;

- reconciliation of spouses;

- termination of work upon retirement.

Fewer points are “given” for changing jobs, vacations, pregnancy, fines for minor offenses, and changing habits. In the Holmes and Ray scale there are only 43 event points that can pull the rug out from under your feet.

To assess the resource and likelihood of developing a nervous or psychosomatic disorder, the authors of the theory recommended noting the events that a person experienced during the year and summing up the points. A high score on the Holmes and Ray scale indicates that the subject has exhausted his resources and needs immediate help.

Symptoms of cardiomyopathy

Unfortunately, cardiomyopathy can occur for a long time without any symptoms, and then manifest itself with symptoms common to many cardiac diseases:

- shortness of breath with minor physical effort, walking;

- arrhythmias;

- pain in the heart area;

- constant loss of strength;

- dizziness;

- fainting states.

Often, cardiomyopathy can be suspected only when the disease is already in the stage of decompensation and all the symptoms of heart failure are present:

- shortness of breath even at rest;

- presence of swelling in the legs;

- ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity), enlarged liver, etc.;

- atrial fibrillation and other types of arrhythmias;

- cough that gets worse when lying down;

- attacks of suffocation;

- pulmonary edema.

1 Ultrasound of the heart for cardiopathy

2 ECGs for cardiomyopathies

3 Blood tests for cardiomyopathy

Diagnosis of cardiomyopathy

Diagnosis of CMP should be trusted only to an experienced specialist, since the clinical picture for various pathologies has similar signs.

First, the doctor collects anamnesis and examines the patient (pays attention to skin color, clarifies the presence of edema, measures heart rate and blood pressure, listens to the heart and lungs with a stethoscope).

Next, laboratory and instrumental studies are prescribed:

- blood tests (clinical, biochemical, hormonal status, lipid profile, etc.);

- electrocardiography (ECG);

- Holter monitoring ECG;

- echocardiography (ultrasound of the heart);

- radiography;

- coronary angiography;

- MRI, CT scan of the heart.