The symptom complex of vegetative-vascular dystonia includes many manifestations that affect the functioning of almost all organs. Extrasystole with VSD is a very common symptom and accompanies almost every VSD patient. It is exclusively neurological in nature and in most cases does not threaten the patient’s life, but it brings a lot of inconvenience and leads to an exacerbation of the disease.

What is characteristic of vegetative-vascular dystonia

It is important for a VSD patient to understand that his arrhythmia is of a functional nature. And no matter where exactly and in what quantity it occurs, one thing is clear: the heart is healthy, and the reason lies in something completely different.

Extrasystole in such patients manifests itself when a large amount of adrenaline enters the blood. But as soon as it decreases to normal, all sensations subside. That is, the problem is temporary and reversible. But patients tolerate it very hard. For them, this is like death: heart failures catch them suddenly, they can be repeated for several months and even years, until the cause is eliminated.

At this moment, a person is seized by a feeling of fear. He begins to choke, his legs give way, and he may lose consciousness. The patient becomes pale, begins to rush about, and scream. The sensation in the chest resembles a blow to the rib cage.

An even greater fear is the compensatory break after an extraordinary compression. The patient fears that his heart will stop. It seems to him that he will die, and this cannot be avoided.

If the excitement intensifies, then the symptoms worsen. Atrial fibrillation occurs. It seems that the heart works outside the regime, chaotically, as it pleases. Fortunately, this condition rarely occurs.

Extrasystole, its treatment with folk remedies

Extrasystole . we can say that this is the most common arrhythmia that is not familiar to us. Extrasystoles can occur in patients, but it is also quite possible for them to occur in practically healthy people. Most often, the cause is stress or possible overwork, under the influence of caffeine, alcohol and tobacco.

The statistical, normal norm for a completely healthy person can be considered up to 200 ventricular and 200 ventricular extrasystoles per day. But, for some completely healthy people there may be more extrasystoles - even possibly up to several tens of thousands per day. Extrasystoles, in themselves, are completely safe; they are sometimes called “cosmetic arrhythmias.”

Extrasystole is a fairly common occurrence in life, for modern society, which at the same time does not require any treatment at all. In order to make your general well-being better and at the same time speed up the process of normalizing your heart rhythm, you can use not only special pharmaceuticals, but also many popular recipes. I would like to note that in this case, old and proven traditional medicine is much better and more effective, since it is not capable of causing the development of possible side effects. There are some recipes for treating extrasystole with folk remedies.

You need to take two teaspoons of valerian roots. then fill them with 100 milliliters of water and leave on the fire for about 15 minutes. After which the broth needs to be strained and cooled, you can take 1 tablespoon, a tablespoon in the morning, at an offensive time, in the evening, and preferably before bed. The important thing is that it is advisable to take the decoction before meals.

When fighting extrasystole, the following recipe is also suitable: You need to take one tablespoon, a tablespoon of lemon balm. herbs, pour it with two and a half glasses of boiled water and leave to infuse. Afterwards, the resulting infusion must be filtered and taken half a glass in the morning, lunch and evening. The course of treatment for extrasystole with folk remedies takes about two to three months, after which you need to take a week's break and you can continue therapy. Another excellent remedy that can help is a composition of black radish with honey - it will help well against extrasystole. To do this, you need to take one to one, black radish juice and an even amount of honey, all this must be mixed thoroughly. We received the remedy, as we always do, we take a tablespoon in the morning, during lunch and, of course, in the evening. If you use one of the proposed folk recipes, then do not forget about the usual healthy lifestyle.

You need to pour 10g of dry hawthorn fruit. 100 ml of vodka or 40-proof alcohol, the resulting mixture must be infused for 10 days, then strained. The infusion can be taken 10 drops with water, 3 times a day and before meals. Remedies that were prepared from hawthorn increase coronary blood circulation, tone the heart muscle, eliminate arrhythmia and tachycardia, lower blood pressure, and reduce the excitability of the central nervous system.

Herbs also help very well, horsetail grass - 2 parts and knotweed grass - 3 parts, blood-red hawthorn flowers - 5 parts. Take a tablespoon from the prepared mixture and pour it all into one glass of boiling water, preferably in a thermos, and leave overnight. The resulting infusion must be strained, after which you can take 1/3 - 1/4 cup 3 - 4 times a day, it helps very well with rapid heartbeat, insomnia, and irritability.

We recommend visiting the “Diets” section of the website and choosing a diet to suit your taste, or sharing your weight loss experience on the forum “How to lose weight, diets, nutrition.

Why do extrasystoles occur during VSD?

Cardiac “dancing” in vegetative-vascular dystonia can occur when both parts of the autonomic nervous system are disrupted.

If the sympathetic department fails, extrasystoles appear after physical exertion. They are poorly controlled by sedatives, and may even intensify after taking them.

If the functioning of the parasympathetic system is disrupted, in addition to cardiac symptoms, digestive disorders are of concern: epigastric pain, diarrhea, bloating. A cup of coffee or sweet tea or a brisk walk will help relieve such an attack.

If the cause is psychological, treatment measures are directed in the other direction.

Most often, dystonics are bothered by two types of extrasystole:

- Ventricular. Usually makes itself felt in the first half of the day. It is caused by disturbances in mental balance, for example, great joy or grief. It also appears when the weather changes or when drinking strong drinks. Other provoking factors include magnesium and calcium deficiency, osteochondrosis. It all starts with an intense beat in the heart area, followed by a pause. The patient becomes covered in cold, sticky sweat and develops a feeling of fear. Despair sets in, he cannot choose a comfortable position for himself, becomes numb or begins to fuss. The violence of his heart leads him into an uncontrollable state, causing him a lot of suffering.

- Supraventricular. The most common type of arrhythmia in VSD. The causes of this condition coincide with those of the ventricular form. In addition, dystonics who are addicted to antiarrhythmic and diuretic drugs are at risk. Patients claim that the condition worsens when lying down. It is this sign that indicates that the cardiac failure is functional in nature.

Extrasystole and other signs of VSD

Considering that extrasystoles cause severe discomfort to dystonics and knock them out of their normal state, they become the cause of the development of other symptoms of VSD. These include:

- increased sweating;

- irritation;

- worry and anxiety;

- weakness and malaise;

- chills and feeling of heat.

Panic attacks that occur during heart dances become the basis for the formation of cardioneurosis. A dystonic person risks developing a phobia against the background of such interruptions in the heart.

Attacks of arrhythmia that occur at night disturb the sleep of the sufferer and provoke insomnia. It can also accompany him as a result of constant worry and anxiety.

Extrasystoles in neurocirculatory dystonia, despite their harmlessness, cause circulatory disorders, including cerebral circulation. As a result, the patient experiences attacks of suffocation, lack of air, and dizziness. Shortness of breath appears.

One of the complications provoked by extraordinary heart contractions during VSD is a panic attack. It begins with an attack of panic and fear, accompanied by a feeling of anxiety and tension. Other symptoms include tachycardia, internal trembling and sweating, nausea, suffocation and dizziness. Characterized by unpleasant sensations in the heart area, tingling and numbness of the arms and legs. The panicker is overcome by fear of death, consciousness is confused, and thinking is impaired.

Thus, arrhythmia, being a sign of VSD, provokes the development of other symptoms of the disease and aggravates its course.

EXTRASYSTOLIA: stages of treatment

Extrasystole (ES) is the most common type of rhythm disturbance and is diagnosed in patients with a wide range of diseases, not only cardiac ones. At the same time, its clinical significance varies greatly among different patients, so the treatment of ES requires a differentiated approach. This message will outline the basic principles of treatment for various types of ES.

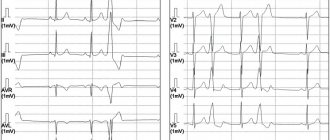

The first step necessary to select adequate treatment is an accurate diagnosis of ES with determination of its origin (ventricular or supraventricular). It is not difficult to suspect that a patient has ES when it is subjectively felt. Often the most unpleasant for the patient is “harmless” functional SE. With ventricular extrasystole (VES), the symptoms are more pronounced, apparently due to an increase in the duration of the pause (a feeling of “cardiac arrest” and a stronger first post-extrasystolic contraction of the heart). To make a diagnosis of ES, a standard ECG in combination with Holter monitoring (HM) is sufficient. Diagnosis of supraventricular extrasystole (SVES) can be difficult in the presence of a wide (E 0.12 s, due to aberrant conduction) QRS complex on the ECG, in most cases - as a right bundle branch block; “early” NVES (superposition of the P wave on the preceding T may cause an error in identifying the P wave); blocked NVES (premature P wave not conducted to the ventricles). To differentiate between VES and NVES with aberrant conduction, a comparison of the shape and coupling interval with previously recorded extrasystoles should be used.

The constancy of the coupling interval and the shape of the P wave (with NVES) or the QRS complex (with VES) is a sign of the monotopy of ES. The need for more accurate topical diagnosis of ES arises in the case of surgical treatment, which is preceded by an electrophysiological study (EPS). Induction of extrasystoles, completely identical to “natural” ones, using a localized stimulus, confirms the accuracy of the topical diagnosis.

CM is carried out to verify the diagnosis of PVCs (especially in the presence of rare extrasystoles that cannot be recorded on a standard ECG), to determine the mono- and polymorphism of PVCs and mainly to determine the number of PVCs during the day, their distribution by time of day and their relationship with various factors. . The presence of no more than 30 ES per hour is considered acceptable. Shorter monitoring may be used (for example, to assess the effectiveness of treatment). ES can also be first detected during various stress ECG tests. If there is a clear anamnestic connection between the occurrence of ES and exercise, these tests can be performed specifically to verify the diagnosis of ES (usually ventricular); in these cases, conditions must be created for possible resuscitation. The association of PVCs with exercise most likely indicates their ischemic etiology.

At the same time, idiopathic PVCs can be suppressed by physical activity.

The second stage - and one of the most important - on the path to selecting adequate therapy for ES is determining its etiology, knowledge of which, in addition to the possibility of carrying out etiotropic therapy for a number of diseases, allows you to determine the prognostic value of ES in a particular patient and select an antiarrhythmic drug. Therefore, all opportunities should be used to make an etiological diagnosis, which in therapeutic practice is of much greater importance than determining the electrophysiological mechanism of ES (reentry or trigger activity).

First of all, it is necessary to identify those causes of SE that can be eliminated (effective etiotropic therapy is possible), without which SE therapy will not be successful:

1. Abuse of tea, coffee, alcoholic beverages (including beer), heavy smoking, taking psychostimulants, drugs, methylxanthines, tricyclic antidepressants, thiazide and loop diuretics, Cavinton, nootropil, hormonal contraceptives, use of inhaled β-adrenergic agonists. The patient himself may note the connection between interruptions in heart function and one of these factors; in this case, along with underestimation, their role may also be exaggerated. In the case of a fairly acute development of ES, it is necessary to exclude hypokalemia, including that caused by taking diuretics. We should not forget about the possible arrhythmogenic effect of antiarrhythmic drugs IA, IC, III classes and cardiac glycosides (they can provoke not only PVCs, but also NPVS).

2. Hyperthyroidism (thyroid hormone screening is mandatory in patients with ES).

3. Myocarditis, including within the framework of infectious (including infective endocarditis) and autoimmune diseases. The connection between the first episode and “exacerbations” of extrasystole, which flows in waves (with periods of remission) with intercurrent infections, is the most characteristic sign of a history of myocarditis, which led to the formation of post-myocardial cardiosclerosis or remains active (cardiosclerosis is proposed to be considered only as one of the phases of latent myocarditis). In the absence of obvious clinical signs of myocarditis, this diagnosis may be supported by: nonspecific signs of inflammation; antibodies to the myocardium (especially the IgM class), Coxsackie viruses group B, ECHO, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV (up to 10% of those infected suffer from myocarditis), streptococci; nonspecific changes in the T wave on the ECG and conduction disturbances, often at different levels; signs of pericarditis in combination with mosaic contractility disorders, subclinical valve regurgitation, moderate chamber dilatation (possibly only the atria), a moderate decrease in ejection fraction; increased troponin T levels (determined only during the first month of illness); decreased interferon levels and increased tumor necrosis factor (are additional markers of immune myocarditis). The most accurate method for diagnosing indolent myocarditis, the only manifestation of which may be ES, is a myocardial biopsy (not performed in most institutions).

In the absence of signs of myocarditis and the simultaneous presence of an inflammatory focus, which is difficult to “discount” when trying to identify the etiology of ES, it is appropriate to make an assumption about toxic-infectious myocardial dystrophy.

The diagnosis of “post-myocardial cardiosclerosis”, which implies the completion of the inflammation process and the impossibility of etiotropic treatment, is justified when identifying signs of inflammatory myocardial damage without immunological markers of current inflammation. It should be noted the possibility of the existence of a trigger mechanism for PVCs, sensitive to verapamil or β-blockers, in patients with post-myocardial cardiosclerosis.

4. Anemia. Its importance for the development of SE may be underestimated, but at the same time, against the background of an increase in hemoglobin levels, the course of SE significantly improves.

For other diseases accompanied by ES, the possibilities of etiotropic therapy are significantly limited (often it is impossible), however, making an accurate etiological diagnosis remains important. Similar causes of ES include the following factors:

- IBS. ES can serve as an early clinical manifestation of myocardial infarction, be of a reperfusion nature (and in this case it does not require treatment), reflect electrical instability in the area of the post-infarction aneurysm (reminiscent of infarction QRS) and be a manifestation of diffuse cardiosclerosis. When performing a treadmill test, the appearance of paired VVCs at a heart rate < 130/min in combination with ischemic ST changes is important. We can speak with confidence about the non-coronary nature of PVCs only after coronary angiography. NVES can also be a manifestation of coronary artery disease, but has a lesser effect on the prognosis in these patients.

- Dyshormonal myocardial dystrophy is usually diagnosed in women. In these cases, ES can occur with dysovarian disorders - in puberty, with premenstrual syndrome, against the background of ovarian dysfunction of various origins, with uterine fibroids (“myomatous heart”) and, of course, in the menopause. Often the stigma of trouble in this area is fibrocystic mastopathy. The presence of dyshormonal myocardial dystrophy can also be assumed in individuals with signs of dyspituitarism; in this case, of course, autonomic imbalance should also be taken into account - within the framework of hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction. ES in such individuals can be either ventricular or supraventricular.

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). PVC is one of the earliest symptoms and largely determines the prognosis; the development of NWES is uncharacteristic.

- Dilated cardiomyopathy. It is characterized by a combination of VES with NVES, which eventually turns into atrial fibrillation (AF). Often, PVC develops as part of alcoholic cardiomyopathy. For familial forms of the disease, a combination with AV blocks of varying degrees, Duchenne or Emery-Dreyfus myodystrophy is typical.

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy can also be accompanied by the development of VES and NSES in combination with blockades; the ECG shows a decrease in voltage. Amyloidosis can occur not only with restrictive changes, but also in the form of isolated atrial damage with the development of NVES and AF. In all cases of unclear heart disease, it is advisable to perform a biopsy of the mucous membrane of the gums and rectum for amyloid. Heart damage is most typical for primary and familial amyloidosis. Isolated cardiac damage does not exclude the presence of amyloidosis, but detection of weakness, fever, weight loss, purpura, macroglossia, lymphadenopathy, neuropathy, hepatosplenomegaly, enteropathy, and nephropathy makes the diagnosis more likely.

- Heart defects (congenital and rheumatic). PVC appears relatively early in aortic defects and may first develop during treatment of MA with cardiac glycosides. Mitral defects (especially mitral stenosis) are characterized by the early appearance of NVC due to overload of the right ventricle. Early development of PVCs with mitral valve disease may reflect active rheumatic carditis.

- Hypertonic disease. The severity of PVCs usually clearly correlates with the degree of left ventricular hypertrophy; a provoking factor may be the use of potassium-sparing diuretics. NVES is less typical and apparently reflects severe diastolic dysfunction with the development of mitral regurgitation.

- Chronic cor pulmonale. Characteristic is the appearance of NVES and right ventricular ES, which is combined with deviation of the heart axis to the right, signs of right ventricular hypertrophy, P-pulmonale, and conduction disturbances in the system of the right bundle branch.

- Sarcoidosis. Mostly young and middle-aged people are affected, more often women; isolated heart damage is uncharacteristic. In the presence of typical changes in the lungs, evidence of sarcoidosis of the heart can include: syncope, persistent cardialgia, a picture of dilated (less often, restrictive) cardiomyopathy, a combination of AV block, right bundle branch block and ventricular arrhythmias. The method for verifying the diagnosis is a biopsy (intrathoracic lymph nodes, liver, skin); An additional diagnostic test is to detect elevated levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme (synthesized by granuloma cells).

- Hemochromatosis. Mostly men aged 40–60 years are affected, but the heart is usually affected in those who become ill at a younger age. Heart damage (restrictive or dilated type) occurs in 15–20% of cases and can be combined with bronze coloration of the skin, arthropathy of the second and third metacarpophalangeal joints, hepatomegaly, and diabetes mellitus. NVES is more common than VES; AV block of varying degrees and supraventricular tachyarrhythmias are possible. The most specific are an increase in the level of serum iron, ferritin, a high - up to 55% or more - percentage of transferrin saturation, a decrease in the total iron-binding capacity of serum (TIBC), hemosiderin with fibrosis and cirrhosis in liver biopsy, as well as confirmation of a specific mutation in a genetic study.

- Mitral valve prolapse, especially in the presence of a prolonged QT interval (in 25%), mitral regurgitation and additional chordae (more often, but not necessarily in people with the stigmata of mesenchymal dysplastic syndrome). PVCs are more often observed in the presence of myxomatous valve degeneration and mitral regurgitation. NVES develops against the background of severe mitral regurgitation.

- Heart operations.

- Tumors of the heart (rarely) affecting the ventricles, pericardium, and atria.

- Heart injuries.

- "Heart of an Athlete" Characteristic is a combination of various rhythm disturbances (including ES) and conduction against the background of myocardial hypertrophy with inadequate blood supply.

A special etiological group consists of genetically determined diseases, in which arrhythmias (PVS, ventricular tachycardia (VT), less commonly, NVES, supraventricular tachyarrhythmias) are the main clinical manifestation. In terms of the degree of malignancy of ventricular arrhythmias, this group is close to ischemic heart disease. These diseases include primarily arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), which must be excluded in all patients (especially young and middle-aged women without obvious heart pathology) who have mono- or polytopic right ventricular ES. When VT occurs, most patients experience syncope.

The criteria for the diagnosis of ARVD proposed by the European Association of Cardiology in 1998 are presented in the table.

Also characteristic are deviations of the EOS to the right, conduction disturbances in the system of the right bundle branch, the ratio of the QRS width in the opening. V2 and V4 more than 1.1. A normal ECG with an arrhythmic history of more than 5 years makes the diagnosis of ARVD unlikely. The diagnostic standard is cardiac MRI: lesions with a diameter of several mm are identified, and the content of adipose tissue is calculated. EchoCG reveals an increase in the end-diastolic diameter of the right ventricle and disturbances in its contractility. When ventriculography is specific, the combination of aneurysms of the wall of the right ventricle and increased trabecularity of the apex.

Other monogenic channelopathies (congenital syndromes of long and short QT interval, Brugada syndrome) are manifested almost exclusively by ventricular tachycardia - the development of VVCs (and especially NVES) is uncharacteristic for them. In WPW syndrome, PVCs and NPVS are not a common symptom; they are combined with other arrhythmias that are more specific to the syndrome (primarily supraventricular tachycardias and AF).

In the absence of all of the above reasons, ES is regarded as idiopathic. The so-called “functional” (as opposed to organic) extrasystole is characterized by the following features, which should be assessed together: the absence of visible organic damage to the heart; constitutional features (in particular, mesenchymal dysplasia syndrome); signs of vegetative dystonia; emotional lability; the occurrence of extrasystoles at rest; often young and middle-aged. It is often possible to identify a connection between NSES and the activation of the sympathetic (during exercise) or parasympathetic (during sleep, after eating, in the presence of a hiatal hernia, cholelithiasis, prostate adenoma) nervous system.

Idiopathic PVCs and tachycardia from the anterior wall of the left ventricular outflow tract occur against the background of vagotonia; ectopic activity predominates at night against the background of a slowdown in the basic rhythm, is suppressed by physical activity, PVCs have a large (not “R to T”) and constant coupling interval, arrhythmias are continuously recurrent in nature. PVCs and tachycardia from the outflow tract of the right ventricle have the morphology of left bundle branch block with moderate widening of the QRS complex and the “right” axis, are provoked by stress and physical activity, and are triggering.

At the third stage, a decision is made on the need for treatment of ES. Indications for the use of antiarrhythmic drugs (AAP) are:

a) poor subjective tolerability of ES (in some cases, psychotropic drugs can be used, AAP can be prescribed situationally); b) prognostically unfavorable ES: frequent (more than 1–1.5 thousand/day) NSES in patients with atrial dilatation, especially against the background of organic myocardial damage (heart defects, dilated cardiomyopathy) threatens the transition to AF; malignant (according to JT Bigger) VES (fainting or cardiac arrest in the anamnesis, there is a heart disease, the frequency of VES is 10–100/hour, stable paroxysms of VT are often detected) and potentially malignant (there is no history of fainting or cardiac arrest, VT is unstable) PVCs threaten the development of ventricular fibrillation; c) regardless of tolerability - frequent ES (more than 1.5–2 thousand/day), which itself can lead to arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy with a decrease in myocardial contractility. Thus, it is possible to refrain from treatment only in cases of relatively rare ES, which is well tolerated and occurs in patients without serious organic myocardial damage, as well as without a history of episodes of AF and ventricular tachycardia. Moreover, this rule does not apply to acute cases of ES, when the cause of its occurrence is not entirely obvious, but nevertheless, one can think about the action of some arrhythmogenic factors that will persist over time and, in the absence of treatment, can lead to the consolidation of ES.

At the fourth stage (after deciding on the need for therapy), an AAP is selected taking into account the type of ES, its etiology, prognostic significance, initial ECG parameters (heart rate, PQ, QT intervals, duration of the QRS complex), previous treatment experience, concomitant diseases and allergic reactions.

It should be remembered that β-blockers and Ca antagonists (verapamil, diltiazem) are effective mainly for NVC and only for certain (trigger mechanism, usually idiopathic), rare variants of PVC, the features of which are described above. Of the class I drugs, allapinin, etacizine, disopyramide, propafenone and flecainide (not available in Russia) have a universal effect (on both NSES and VES). Quinidine should not be prescribed in the presence of ventricular ectopy; ethmozin and class IB drugs (lidocaine, mexiletine, diphenine) are effective only for PVCs. Representatives of class III AAPs d,L-sotalol and amiodarone are equally effective in cases of PVCs and NPVS; “pure” class III AAPs in isolated ES are usually not prescribed (due to their serious proarrhythmogenic effect, they are used only for paroxysmal tachycardias resistant to other drugs), although they are capable suppress both VES and NSES.

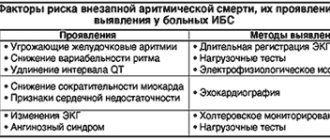

The etiology of ES only to some extent determines the choice of AAP. Thus, in case of thyrotoxicosis, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, HCM, the prescription of b-blockers (in case of HCM - and calcium antagonists) is pathogenetically justified, while in case of ES in combination with paroxysmal tachycardia against the background of WPW, verapamil is contraindicated; ajmaline can be used; for ARVD, d,L-sotalol is the most effective; for digitalis ES, diphenine is very effective (and safe); for PVCs, lidocaine is used predominantly in the acute period of myocardial infarction. Ethmozin is most effective for PVCs of ischemic origin. Taking into account the etiology, the prognosis of ES is also determined - serious organic damage to the myocardium in various diseases is associated not only with a high risk of transition of ES into life-threatening arrhythmias, but also with the risk of developing the proarrhythmic effect of AAP of classes IA, IC and III and requires caution when prescribing these drugs. In the early post-infarction period, only class IB drugs, amiodarone and, apparently, d, L-sotalol, are safe. For other organic pathologies, the approach must be individual. In order to reduce the risk of transition of PVCs to fibrillation, as well as the development of the proarrhythmic effect of AAPs (primarily tachycardia of the “pirouette” type), in addition to AAPs of classes I and III, beta-blockers should be prescribed whenever possible (especially in the presence of sinus tachycardia). If NVES is highly significant (for example, in patients with mitral stenosis), amiodarone can be immediately prescribed to suppress it. In case of VES, to improve the accuracy of the prognosis, a complex of predictors of sudden death is additionally used, each of which individually is not decisive: cardiac arrest or a history of sustained ventricular tachycardia; severe left ventricular hypertrophy; left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40%; presence of late ventricular potentials; increased dispersion of the QT interval over time or space; decreased heart rate variability.

It should also be remembered that most AAPs lead to an increase in the PQ interval (the exception is class IB) and a decrease in heart rate in sinus rhythm, with the most severe effects of propranolol, atenolol, betaxolol, high doses of verapamil and diltiazem (360–480 mg/day). day), d,L-sotalol (160–320 mg/day) and amiodarone (400–600 mg/day); Propafenone also has β-blocking activity. AAPs that increase the rhythm include allapinine (sympathomimetic), quinidine, disopyramide and novocainamide (anticholinergics); This effect is characteristic of etacizin and ethmosin to a much lesser extent. In patients with sick sinus syndrome and initial AV block, the reaction to taking “increasing” drugs may be the opposite. Slowing of intraventricular conduction (QRS widening) is caused by drugs IA, IC (ethacizine, flecainide) and, to a lesser extent, “pure” class III drugs. Amiodarone and d,L-sotalol can be prescribed for moderate (with caution for severe) QRS widening. Class I drugs and, to a lesser extent, class IA and IC drugs lead primarily to prolongation of the QT interval with the risk of developing tachycardia of the “pirouette” type - with a QT with more than 460–470 ms, these drugs should not be prescribed. QRS widening and QT interval prolongation are not a contraindication to the use of β-blockers and Ca antagonists. It should be noted that a moderate and non-progressive increase in the duration of the PQ interval (up to 0.22–0.24 s), as well as moderate sinus bradycardia (up to 50 beats/min) are not indications for discontinuation of drugs, subject to regular monitoring ECG.

Finally, if there is a history of ineffectiveness of one of the β-blockers or calcium antagonists in adequate doses, there is no point in prescribing another representative of the same class of AAP. At the same time, representatives of class I AAP, as well as amiodarone and d,L-sotalol, have significant differences and should be tested independently of each other (it does not make sense to replace the ineffective ethacizin with ethmosin or poorly tolerated ethmosin with ethmosin, since ethmosin is weaker metabolite of etacizine). If you want to prescribe etacizin, you should exclude an allergy to honey.

So, there is all the preliminary data in order to choose one or another AAP. In case of NVC, especially in patients with tachycardia, stress-induced ES, in the presence of other indications for the use of β-blockers (coronary heart disease, arterial hypertension, sympathoadrenal crises, etc.) or verapamil (bronchial asthma, variant angina, nitrate intolerance in patients with coronary artery disease) Treatment of NJES begins with these AAPs. β-blockers include propranolol 30–60 mg/day, atenolol or metoprolol 25–100 mg/day, bisoprolol 5–10 mg/day, betaxolol 10–20 mg/day, nebivolol 5–10 mg/day); verapamil or diltiazem are prescribed in doses of 120–480 mg/day. In case of simultaneous presence of NZHES and VES, a more rational drug is d,L-sotalol (80–160 mg/day). At the same time, patients with vagus-mediated NVES are prescribed belloid, 1 table. 4–5 times a day, small doses of teopec (50–100 mg 2–3 times a day and at night), nifedipine, taking into account their rhythm-increasing effect; in this case, the circadian rhythm of NVES is taken into account (if NVES occurs against the background of nocturnal bradycardia, drugs that increase the rhythm should be prescribed at night).

If there is a tendency to bradycardia, AAPs that increase the rhythm can be immediately prescribed (disopyramide 200–400 mg/day or quinidine-durules 400–600 mg/day, or allapinin 50–100 mg/day), which are not only safer, but also allow you to act on the pathogenesis of brady-dependent NSES. It makes sense to start treatment with drugs IA or IC class (propafenone is prescribed in a dose of 600–900 mg/day, etacizine - 100–200 mg/day, flecainide - 200-300 mg/day, ajmaline - 200-400 mg/day). patients with a high prognostic significance of NVES, when class II and IV AAPs are generally not so effective. Prescribing amiodarone (200–300 mg/day) for NSES, taking into account the numerous side effects, is advisable only if other therapy is ineffective; however, if it is necessary to quickly achieve maximum effect, amiodarone can be prescribed immediately (without testing other drugs), in a rapid saturation mode. When treating patients with an undulating course of NZHES, one should strive for complete withdrawal of the drug during periods of remission (excluding cases of severe organic damage to the myocardium).

For PVCs of a benign or potentially malignant nature, therapy begins, as a rule, with the prescription of class I AAP (in addition to the previously mentioned universal drugs - ethmozin 400-600 mg / day), and only if they are ineffective - amiodarone or d, L-sotalol. Mexiletine 400–600 mg/day and diphenine 0.117, 1 tablet each. 3 times a day (in the absence of glycoside intoxication) are usually inferior to other AAPs and are prescribed only if there are contraindications to more active treatment. Sometimes novocainamide can be used - 2–4 g/day, i.e. 1–2 tablets. 4–6 times a day, the effectiveness of which for PVCs is quite high, but the dosage regimen for oral administration is inconvenient. For malignant and potentially malignant (in the case of a previous heart attack) PVC, it is preferable to prescribe amiodarone (300–400 mg/day, effective in approximately 50% of cases) or d,L-sotalol (80–320 mg/day). However, d,L-sotalol should be used only in cases where amiodarone is contraindicated or ineffective. In patients with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, the development of thyroid dysfunction is not a reason to discontinue amiodarone. G. A. Melnichenko, N. Yu. Sviridenko et al. (2004) developed an algorithm for monitoring and normalizing thyroid function (both in hypothyroidism and thyrotoxicosis) during long-term therapy with amiodarone. It should be noted that in this category of patients therapy with class I antiarrhythmics is not excluded. Their effectiveness in general is significantly less than that of amiodarone, and the incidence of proarrhythmic effect is higher, however, in a particular patient, a class I drug may be the most effective and safe.

Frequent PVCs require parenteral therapy in cases of acute occurrence or increase in frequency in patients at high risk of sudden death. Lidocaine or amiodarone is administered intravenously as a bolus and subsequently as a drip. The frequency of PVCs may decrease during therapy with β-blockers (with myocardial infarction).

An ineffective drug is usually completely discontinued, and another AAP is prescribed as monotherapy - thus, all potentially effective AAPs for a given patient are consistently tested. If monotherapy is insufficiently effective, combinations of AAPs can be used; in particular, if high doses of d,L-sotalol and allapinine are poorly tolerated, their combination using lower doses is indicated (40 mg x 2 sotalol + 25 mg x 2 or 12.5 mg x 4 allapinine); combinations of allapinin with β-blockers, calcium antagonists are possible, which successfully combine the multidirectional effects of drugs on heart rate, but increase the inhibitory effect on AV conduction; combinations of quinidine (0.4–0.6 mg/day) with β-blockers, calcium antagonists. The prescription of amiodarone in combination with β-blockers for malignant PVCs, especially with persistent sinus tachycardia, is justified. Combinations of class I and III AAPs (especially those including amiodarone) have the most powerful effects; however, with isolated ES, such aggressive (and unsafe) therapy is usually not required.

Along with the appointment of AAP, the following options should be used:

- Prescription for 1–2 months of glucocorticoids (prednisolone 10–20 mg/day), aminoquinolones (delagil 250–500 mg/day, plaquenil 200–400 mg/day) or NSAIDs (butadione, ibuprofen, voltaren) if current myocarditis is suspected.

- Prescription of tincture of hawthorn, motherwort, as well as benzodiazepines that have an antiarrhythmic (phenazepam 0.5–1 mg) or vegetotropic (clonazepam 0.5–1 mg) effect and improve the subjective tolerability of NVES.

- Prevention of sudden death (with malignant PVC) using aspirin, ACE inhibitors (which apparently also have an antiarrhythmic effect), statins.

- In patients with moderate atrial dilatation, without heart defects, with ischemic and alcoholic origin of ES, with concomitant hyperlipidemia - the use of hemosorption or plasmapheresis with a clear connection between the “exacerbation” of ES with infection, an increase in ES over the last 6 months, with the development of resistance to previously effective antiarrhythmics (especially amiodarone), ineffectiveness of drug therapy or contraindications to it, if it is necessary to achieve an antiarrhythmic effect in the coming months (before surgery).

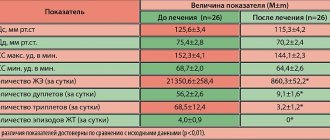

The fifth stage in selecting therapy for ES can be considered adequate monitoring of the effectiveness and safety of treatment. The effectiveness of AAP can be assessed empirically (observation of the patient while taking therapeutic doses), during an acute test (after a single dose of half the daily dose), using a standard ECG (the safety of treatment is assessed to a greater extent; the effect can only be assessed with frequent ES) and optimally - control HM. Firstly, the drug can be evaluated in an acute test (half of its daily dose is prescribed at once, chemotherapy is carried out within 2-3 hours before taking the AAP and for the same time after taking it), however, extrapolation of the data obtained in the acute test to the results of long-term use AAP is not always possible. Secondly, with the help of CM, the effect of planned therapy is assessed - daily CM is carried out before the appointment of an AAP and on the 2-3rd day of its administration, treatment is considered effective when tachycardia runs, steam, early ES disappear, ES decreases by 75-80% after days; An assessment is made of the proarrhythmic effect that occurs during the treatment of conduction disorders.

Finally, at the sixth stage , the insufficient effectiveness of drug therapy serves as the basis for the use of surgical (interventional) techniques. In all cases of frequent (up to 10 thousand/day or more) ES - including those with a known etiology - and resistance to 3-5 AAPs, the question of conducting EPI mapping and ablation of arrhythmogenic foci should be raised. To preliminarily identify such lesions, cardiac MRI is performed. The need to prescribe AAP after ablation often remains (it is lower in patients with idiopathic PVCs and post-myocardial cardiosclerosis), but their effectiveness can be significantly higher than before the procedure; less often it is possible to completely abandon AAP 3–12 months after ablation. Surgical treatment (ablation of arrhythmogenic foci) for ARVD should be quite early, since simultaneously with the relief of arrhythmias (in 75–80%; in 40–50% of patients - with subsequent administration of AAP), fatty replacement of the myocardium is stopped. In later stages of the disease, heart transplantation is necessary. A difficult option for surgeons may be left ventricular triggered PVC, in which the arrhythmogenic focus is located subepicardially near the ostia of the coronary arteries - the risk of developing coronary artery stenosis makes it necessary to refuse radical treatment, however, ablation of the zone adjacent to the arrhythmogenic focus can lead to a change in its electrical properties and the appearance of sensitivity to previously ineffective AAP. In patients with PVCs with post-infarction aneurysm, in principle, the more preferable intervention is aneurysmectomy, which allows simultaneously with the elimination of the arrhythmia substrate to improve hemodynamics, however, such a large-scale operation is not always feasible. In the absence of ventricular tachycardia, the indication for aneurysmectomy is congestive heart failure in combination with PVCs, including allorhythmia.

The need for another type of surgical treatment (implantation of a permanent pacemaker) may arise both in the early stages of selecting therapy and after the prescription of AAP: the impossibility of prescribing adequate doses of AAP due to the development of severe concomitant bradycardia, pauses of ≥ 3 s, and conduction disturbances is an independent indication to install a stimulator.

It is also important to correctly determine the duration of antiarrhythmic therapy. In patients with malignant PVC or NPV that threatens the development of MA, AAP therapy should be continued indefinitely. For less malignant types of ES, therapy should be quite long (up to several months), with the possibility of gradual (due to the danger of the rebound effect) its withdrawal. After discontinuation of continuous therapy, the patient should be advised to constantly carry a well-proven AAP with him and take it when cardiac dysfunction recurs. Usually this is enough.

A. V. Nedostup, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor O. V. Blagova , Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of MMA named after. I. M. Sechenova