The fibrous ring is the outer shell of the intervertebral disc, which is responsible, in principle, for its integrity. It consists of dense cartilage fibers that can quickly adapt to any shock-absorbing loads. Very elastic and hardy. With the development of osteochondrosis, pathological changes primarily affect the fibrous ring - it begins to crack, become covered with deposits of calcium salts, and loses the ability to receive sufficient amounts of fluid and nutrients through diffuse exchange with the surrounding paravertebral muscles.

As a result of this, various damage to the fibrous ring occurs, most of which will be discussed in the proposed material. Here we talk about how the annulus fibrosus is structured and what main functions it performs. Information is given about the potential causes of destruction of its tissues. Characteristic clinical symptoms are described, when they appear, you should immediately consult a doctor for examination and differential diagnosis. In the article you will learn about modern effective methods for restoring the integrity of the cartilage tissue of the fibrous ring.

If you have symptoms and signs that are described in the material, we recommend that you consult a neurologist or vertebrologist as soon as possible. These doctors have sufficient competence to provide effective and safe treatment for degenerative changes in the intervertebral discs.

In Moscow, you can sign up for a free consultation with a vertebrologist or neurologist at our manual therapy clinic. The appointments are conducted by experienced doctors. They establish a preliminary diagnosis and prescribe additional examinations as necessary. They give individual recommendations for treatment and lifestyle changes so that the spinal column regains its lost health.

You can make an appointment for a free appointment using a special form, which is located at the end of this page. You can also call our administrator and agree on a convenient time for your visit.

Features of the manifestation of fibrosis of heart valves

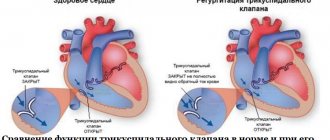

The condition does not worsen immediately. It is possible to identify compaction of the valve wall from the clinical picture of a hemodynamic failure only with the development of severe regurgitation. It is characterized by reverse blood flow. It returns to the atrium or ventricle depending on the affected valve. The essence of the problem lies in the incomplete closure of the valves. Sometimes it happens the other way around. Fibrosis leads to the fusion of the valves with each other. In the first case, the pathological process provokes an enlargement of the atrium, and in the second, a narrowing of the valve opening.

The degree of regurgitation varies between mild and severe. The clinical picture will depend on the severity of the pathology.

Mitral valve damage

If the mitral valve leaflets are compacted, the patient may eventually develop the following symptoms of fibrosis:

- fast fatiguability;

- frequent shortness of breath;

- feeling of heartbeat;

- arrhythmia;

- feeling of shortness of breath;

- pain in the heart area;

- swelling of the legs.

Aortic valve damage

Fibrosis of the aortic valve contributes to the manifestation of cerebral hypoxia. The patient exhibits a pathological process with the following symptoms:

- general weakness;

- pulmonary edema;

- loss of consciousness;

- angina pectoris.

Fibrosis classification

Each form of pathology has its own characteristics.

- The focal form is the basic one. It is characterized by moderate fragmented damage to the structure of the valve apparatus.

- The diffuse type is characterized by a large area of damage (cusps and subvalvular space). It is detected at advanced stages of fibrosis development.

- The cystic form is perceived as a separate pathology. It manifests itself as serious disruptions in metabolic processes and leads to the formation of cysts.

If the cusps of the mitral valve are sealed, then it is not at all necessary that this is a heart defect. Fibrosis is only a pathological change that occurs under the influence of other factors, and not a diagnosis. Because of it, stenosis and valve insufficiency can develop. The appearance of voiced pathologies requires urgent medical intervention. The proliferation of fibrous tissue can be perceived as a substrate for the formation of cardiac muscle defects. However, it is unlikely to predict its development in advance. The chances of timely identification of the problem increase through regular examination.

Induration, calcification and fissure of the annulus fibrosus

At the initial stage of development of osteochondrosis, a gradual thickening of the fibrous ring occurs - this process tells an experienced vertebrologist that the cartilage tissue does not receive sufficient fluid. Induration of the annulus fibrosus does not cause any clinical symptoms and may be detected incidentally during MRI examinations of the spinal column.

A fissure in the annulus fibrosus is the next stage of osteochondrosis. If there is little fluid flow, then the compacted cartilage tissue cannot fully cope with the shock-absorbing loads placed on it. It loses its elasticity and plasticity. A network of small cracks appears that do not completely disrupt the integrity of the fibrous ring.

Against the background of impaired diffuse nutrition, the body sees the only way to restore the integrity of the cracked surface of the intervertebral disc through the deposition of calcium salts. Secondary calcification of the annulus fibrosus is a serious pathology that significantly reduces the ability of cartilage tissue to absorb fluid secreted by the endplate and paravertebral muscles. With its development, osteochondrosis begins to rapidly destroy the intervertebral disc.

What it is?

You can understand what fibrosis of the mitral valve leaflets is by looking at the features of its structure and functioning.

The essence of the operation of the valve apparatus is to allow blood to pass (in one direction) when a certain section contracts. The main role is played by the valves, which are represented by loose connective tissue. Their nutrition is carried out through the smallest vessels. The aortic valve has three leaflets (right, left, posterior), and the mitral valve has two (posterior, anterior). Under the influence of irritating factors, the connective tissue becomes coarser, which is why it ceases to fully perform its functions (maintain the flexibility of the valves). Over time, the number of blood vessels supplying the valve is significantly reduced. The cells that make up it begin to die, being replaced by fibrous tissue. It is one of the types of connective tissues, which is characterized by high strength.

Protrusion of fibrous rings

At its core, protrusion of the fibrous rings is the second stage of osteochondrosis. Degenerative dystrophic changes in intervertebral discs reach the next level. The fibrous ring, unable to absorb fluid from the outside, begins to take moisture from the structure of the nucleus pulposus. It quickly decreases in volume and can no longer support the normal height of the disc.

This results in an increase in the area occupied by the disk. It begins to extend beyond the vertebral bodies that it separates. This begins to exert irritating pressure on the surrounding soft tissue. A persistent pain syndrome appears, which is difficult to relieve with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Protrusion with rupture of the fibrous ring is called extrusion. If, in the process of violating the integrity of the fibrous ring, part of the nucleus pulposus falls out, then this is a disc herniation. Extrusion is the third stage of osteochondrosis.

Fibrosis of the mitral valve leaflets

Fibrosis of the mitral valve leaflets is a rather dangerous and serious condition. The reasons for its occurrence are very diverse. It is worth considering them in more detail.

Causes

Quite often, this disease appears after the patient has suffered a myocardial infarction. A common cause is age-related changes in the human body. Over the years, tissues and organs wear out. Heart tissue and urinary tract can be damaged due to hormonal changes, rapid slowdown of metabolism, etc.

- Life against the tide. Mitral valve prolapse and what is behind it

Mitral valve fibrosis can also be caused by the following reasons:

- Hypertension.

- Lung dysfunction.

- Heart defects.

- Infectious or viral infection of the connective tissues of the heart.

- Strong physical activity, etc.

This disease, in the absence of timely intervention by specialists, can develop into myocardial fibrosis. Otherwise it is called myocardiofibrosis.

“Senile” heart disease: truth and myths

What is hidden behind the diagnosis of “atherosclerotic aortic stenosis”? What is the mechanism of development of aortic stenosis? Is there a difference in treatment tactics in Russia and abroad?

| Picture 1 |

Many therapists and cardiologists are well aware of this frequently occurring clinical phenomenon: in an elderly person without a rheumatic history, when listening to the heart, a rough systolic murmur is detected over the aortic points.

Often it is practically not interpreted in any way and is not reflected in the diagnosis. But sometimes, in an attempt to explain such an auscultatory picture, the doctor still makes something like this verdict: “atherosclerotic stenosis of the aortic mouth.” But we must not forget that a diagnosis is a formula for treatment, and further tactics largely depend on how correctly it is formulated. This applies to any diagnosis, and this one in particular. That is why it is necessary to seriously understand not only and not so much the validity of the term “atherosclerotic stenosis”, but what actually hides behind a “non-rheumatic” systolic murmur at the base of the heart. In the USSR, three main causes of acquired aortic stenosis were traditionally considered: 1) rheumatism, 2) infective endocarditis and 3) atherosclerosis. It was this triad, and, as a rule, in exactly this order, that migrated from manual to manual, from one textbook to another until the middle of this decade, while other prerequisites were given a place in the “and others” column. Most authors, after describing rheumatic and “septic” endocarditis in one form or another, mention atherosclerosis, which usually in old age can lead to the formation of calcified stenosis of the aortic valve [1].

Meanwhile, people abroad have held a different point of view for more than 30 years. It is consistently discussed in English-language sources published in the 60s, 70s and 80s, and the last decade is no exception. According to Western researchers, aortic stenosis in adults can be the result of: 1) calcification and dystrophic changes of the normal valve, 2) calcification and fibrosis of the congenital bicuspid aortic valve, or 3) rheumatic damage to the valve, with the first situation being the most common cause of aortic stenosis [2] .

So, there is an obvious difference in approaches to this problem in Russia and abroad. The “crossing point” was and remains only rheumatism, while domestic and foreign schools each “supplement” it with two different etiological forms: the first - infective endocarditis and atherosclerosis, the second - idiopathic calcification and calcification of a congenital defect (usually the bicuspid valve). But keep in mind that there are two caveats. Firstly, isolated calcification of both the tricuspid and bicuspid aortic valves is essentially the same process, observed only in different time ranges. Secondly, infective endocarditis, by the work of modern authors, is actually excluded from the list of significant causes of aortic stenosis. Thus, by and large, there remain two conditions that determine diagnostic, therapeutic and methodological discrepancies: atherosclerosis and idiopathic calcinosis. The fundamental difference between these two pathological conditions will become clear after a more detailed consideration of senile calcification of the aortic mouth as an independent nosological form.

- Morphological aspects

In 1904, in the journal Archives of Pathological Anatomy, 28-year-old German physician Johann Georg Menckeberg described two cases of aortic stenosis with significant calcification of the valves [3]. He proposed to consider changes in the valves as degenerative, as a result of tissue wear followed by their “sclerosis” and calcification. Having apparently discovered something similar to what is shown in Fig. 1, he depicted in his article a deformed valve, in which, against the background of fatty degeneration, there are many calcareous deposits (Fig. 2). His correctness will be confirmed many years later, which will be reflected in the very term “degenerative calcified aortic stenosis.” But at the beginning of the century, I. G. Menkeberg’s article did not cause a significant resonance. And only after a decade and a half it will become the object of attention and form the basis of heated discussions that have been going on for a long time. The morphogenesis of the defect also caused a lot of controversy.

| Figure 2 |

Mainly two theories competed with the Mönckeberg hypothesis: atherosclerotic lesions and post-inflammatory calcification.

In our country, the atherosclerotic hypothesis has acquired primary importance. It is believed that a detailed study of “atherosclerosis of the aortic valve” in the dynamics of the development of “atherosclerotic defect” was carried out by Professor A.V. Walter in the late 40s. He described intense lipoid infiltration of the fibrous layer of the valve at the level of the closing line and at the bottom of the sinuses of Valsalva, and he also observed lipoid deposition on the sinus surface of the valves in small thickenings of the subendothelial layer. Next, petrification of lipomatous lesions took place. The calcareous masses split, which the researcher explained by the mobility of the valves, and the resulting cracks are filled with plasma proteins and new portions of lipoids, in which calcium is again deposited. The splitting of petrification continues, and after this the calcification of the valve continues. The fibrous ring becomes rigid, the valves are hard and inactive. Aortic stenosis develops [4].

It seems that in 1948 the publication of these data was enough to substantiate the atherosclerotic hypothesis, although even the very idea of “splitting” of petrified masses requires critical reflection: if it had taken place, the frequency of microembolic complications would probably have increased significantly. Today, when knowledge about atherogenesis is much more extensive, it seems possible to put forward at least two counterarguments to the theory of A.V. Walter.

- It is now known that the main anatomical substrate that requires lipids for metabolism is the myocyte. It is smooth muscle cells that utilize substances transported into the arterial wall by plasma lipoproteins. The predominant damage by atherosclerosis to the inner, rather than the middle layer of the vascular wall is explained by the fact that normally in old age the intima thickens due to the movement of smooth myocytes into it from the media with subsequent proliferation. In other words, the intima owes much of its infiltration of cholesterol esters to smooth muscle cells. So, these are the ones that are practically absent in the leaflets of the aortic valves. Modern histologists point to this [5], this was mentioned in 1904 by Menkeberg himself.

- According to the current theory, atheromorphogenesis includes three stages: fatty streaks or spots, fibrous plaques and, finally, complicated lesions, which include calcification of the fibrous plaque. That is, the stage of calcification in atherosclerosis must be preceded by a stage when extracellular cholesterol mixed with detritus appears under the lens, covered with a special visor of a large number of smooth myocytes, macrophages and collagen. Professor A.V. Walter did not describe anything like this. And not by chance. In 1994, that is, almost 50 years after the publication of Walter’s work, V.N. Shestakov describes the morphogenesis of this defect as follows: “The initial phase of this process is lipoid infiltration of the valve surfaces facing the sinuses of Valsalva. In areas of lipoidosis, deposition of calcium salts begins. This process slowly progresses, leading to limited mobility of the valves” [6]. As can be seen, these observations are fundamentally similar, and both lack the fibrous plaque stage. In addition, as American scientists have long proven, in the pathology we are discussing, in contrast to atherosclerotic damage, there are no cholesterol crystals [7]. As far as can be judged from English-language periodicals, there is also no correlation between calcified aortic stenosis and the severity of general atherosclerotic lesions, including the aorta itself in a given patient.

The line under these considerations can be summed up with an excerpt from an article on atherosclerosis by Professor E. Bierman at the University of Washington: “It should not be confused with atherosclerosis <...> local calcifying lesion of the aortic valve, when with age there is a gradual accumulation of calcium on the aortic surface of the valve” [8].

The post-inflammatory hypothesis, widespread mainly in the West, suggested looking for a connection between calcification and a history of infective endocarditis, or, more likely, latent rheumatic carditis. Thus, some researchers point to the presence of microbial agents in calcium conglomerates [9]. Others report the results of a histological examination of 200 calcified aortic valves, 196 of which showed signs of rheumatic lesions [10]. Now it is difficult to give an objective assessment of such data, but, probably, these were sectional finds in people who were not so elderly and without pronounced calcareous deposits. These are the conclusions you come to when studying the opinion of modern pathologists, who claim that in old patients the massiveness of petrification always masks the signs, perhaps, of a history of rheumatic endocarditis.

However, the approach that emerged in the first half of the century led to the formation of two views that are now prevalent abroad. One of them suggests that rheumatic valvulitis, even without leaving persistent granulomatous lesions, makes the valve more vulnerable in the future, significantly increasing the risk of structural degeneration [11] and allowing senile aortic stenosis to be considered truly “degenerative”, whereas post-inflammatory dystrophy, post-rheumatic degeneration; at the same time, the transferred inflammation seems to determine the connective tissue destruction of the valves in old and senile age, turning out to be a kind of predictor of calcification of the aortic valve apparatus. According to another view, senile calcified stenosis is not so much the result of infective endocarditis, but can itself be caused by an infectious pathogen that persists in the aortic valves [12], that is, we are generally talking about a completely independent nosological form.

The uniqueness of the pathology under consideration is also evidenced by the fact that more and more often there are publications about the discovery of various bone tissue cells and even elements of red bone marrow in the calcified cusps of the aortic valve [13].

- Clinical aspects

The reminder of the well-known signs of aortic stenosis to the medical audience in this case is not accidental. The fact is that in elderly and elderly patients, doctors are often inclined to explain the presence of certain complaints more likely by coronary disease or general involutive processes in the body, rather than by a mature “senile” heart defect. Therefore, briefly about the main features of this disease.

| Figure 3 |

Aortic stenosis is one of the most long-term compensated defects due to myocardial hypertrophy, which is as severe as can be found in other heart diseases (Fig. 3). In this regard, the end-diastolic pressure in the left ventricle increases significantly, its filling (especially during physical activity and in conditions of tachycardia) becomes more difficult, which gradually leads to an increase in the wedge pressure of the pulmonary artery. The shortness of breath that develops, thus, at first turns out to be a consequence of primary diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle, and during the period of decompensation - also of systolic dysfunction. Increased myocardial tone in diastole is also associated with impaired oxygenation. While the increase in left ventricular mass increases the myocardial oxygen demand, the compressed coronary arteries cannot satisfy it. Hence the angina pain that is so typical for this category of patients. Moreover, although angina occurs in 70% of patients with aortic stenosis, only half of them have coronary atherosclerosis [2]. The third common complaint - fainting - is a consequence of a decrease in cardiac output, which develops as a result, on the one hand, of a decrease in diastolic filling of the ventricle, and on the other, an increasing pressure gradient at the level of the aortic valve [14]. Dizziness can be equivalent to syncope.

Among the complications of senile stenosis, embolism with crumbling calcareous masses (most often of the coronary, renal and cerebral arteries), poorly tolerated and prognostically unfavorable arrhythmias (associated with both ischemic myocardiopathy and enlargement and dysfunction of the left atrium) and rarely developing gastrointestinal bleeding should be noted associated with angiodysplasia of the right colon. At the same time, the risk of infective endocarditis of calcified valves is reduced in comparison with isolated aortic stenoses of rheumatic etiology.

On examination, it is rare to find anything specific for degenerative stenosis in elderly patients. Unlike young patients, who often have a “slow and small” pulse, even with severe stenosis, due to a decrease in the elasticity of the arteries, the pulse can remain normal. By palpation, a long ascending apical impulse is determined in the 5th intercostal space somewhat outward from the midclavicular line; Systolic tremor may often be palpable. During auscultation, the first tone may not change, but due to functional-hemodynamic changes, it is often observed

| Figure 4 |

weakening

In this case, the second tone, as a rule, changes, which is especially clearly recorded during long-term observation of the patient: while valve calcification has not led to stenosis, the second tone is intensified (at the same time, at the Botkin point, after the first sound, a systolic ejection tone is sometimes heard), then from -due to reduced mobility of the valves, it is weakened. Aortic stenosis is characterized by a rough fusiform systolic murmur, heard maximally at the left edge of the sternum and carried to the carotid arteries. With senile lesions, this noise has some pathogenetic features (Fig. 4). As can be seen from the diagram, a rheumatic calcified defect creates a hemodynamic “jet” effect during systolic expulsion, giving rise to only auscultatory phenomena, and an isolated calcified stenosis creates a “spray” effect with slightly different hemodynamics and nuances of the auscultated picture [15]. Thus, with severe petrification, Gallawarden's symptom occurs: high-frequency components of the noise are conducted into the axillary region, simulating the noise of mitral regurgitation. In the diagnosis, the clinician will be helped by routine instrumental techniques: ECG (signs of hypertrophy and impaired blood supply to the left ventricular myocardium, arrhythmias), radiography (calcification of the aortic valve, changes in the configuration of the heart, signs of congestion in the lungs) and, of course, EchoCG (the nature of changes in the valve leaflets, accurate assessment of the degree of stenosis and hypertrophy of the myocardium, measurement of intracardiac hemodynamics, impaired local contractility, ejection fraction, pressure gradient between the aorta and left ventricle).

Laboratory indicators, as a rule, are unspecific and reflect extracardiac pathology.

- Treatment tactics

The prognosis for isolated degenerative aortic stenosis is determined by the degree of narrowing of the aortic valve opening (see table), but in general, as a rule, is favorable. This is determined by long-term compensation with an asymptomatic course and slow progression due to the absence of commissural adhesions, as in rheumatic disease. It should be remembered that when symptoms appear, mortality and the risk of complications increases sharply, and 15-20% of patients die suddenly.

In Russia, this nosology as such has not been studied, which means that the practicing physician is not focused on the appropriate diagnostic search. At the same time, the rather rare diagnosis of “atherosclerotic aortic stenosis” due to a lack of understanding of the true nature of the defect leads to the fact that the patient is more often prescribed a diet and cholesterol-lowering drugs rather than referred for a consultation with a cardiac surgeon. But such “pathogenetic treatment” only leads to the progression of petrified stenosis. Conservative symptomatic tactics are generally ineffective in patients with aortic stenosis, and even more so in patients with calcified aortic stenosis. Vasodilating and inotropic therapy requires great caution, and the use of nitrates and diuretics should be avoided.

Rate of progression of aortic stenosis

|

| * Published according to the manual “Cardiology in tables and diagrams”, M. - Praktika, 1996, p. 343 |

In other words, refusal to interpret senile calcified stenosis of the aortic mouth as “atherosclerotic” will lead Russian cardiologists and therapists to form a completely definite view of the treatment prospects for such patients. The only effective treatment worldwide is surgical treatment, either by aortic valve replacement (the method with the best long-term survival rates) or by balloon valvuloplasty. The second method has a number of significant disadvantages: a high risk of complications and the likelihood of re-obstruction, high intraoperative mortality (>6%) and mortality within a year (25%). Meanwhile, this intervention option remains the main one for elderly patients abroad; and in general, degenerative calcification became the main reason for surgical treatment for isolated aortic stenosis (51% of cases of percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty, while calcification of the bicuspid valve and post-rheumatic lesion - 40 and 8% of cases, respectively). Moreover, the age of the operated patients often exceeds 80 years [16].

When writing the last paragraph, the author, of course, was aware that it was impossible to project a foreign situation onto Russian reality. The frequent somatic “negligence” of our patients and the cost of cardiac surgery in the near future do not allow us to hope for any fundamental changes in this issue. This article has only raised a gerontological problem, which has not been discussed in our country for many years. And the point is not so much that 1999 has been declared “the year of the elderly” - domestic doctors must have up-to-date information and abandon outdated formulations and non-existent diagnoses.

Literature

1. Burakovsky V.I., Bockeria L.A. Cardiovascular surgery. M.: Medicine, 1989. 2. Goldstein JA Aortic stenosis // Essentials of Cardiovascular Medicine / Ed. M.Freed and C.Grines. Birmingham, 1994. 3. Monckeberg, JG Der normale histologische Bau und die Sklerose Aortenklappen // Virchows Archiv fur pathologische Anatomie und Physiology und fur Klinische Medizin, (1904). 176, 472. 4. Walter A.V. Chronic aortic valve defects. L., VMMA, 1948, p. 23-88. 5. Ham AW, Cormack DH Histology / JB Lippincott Company, NY 1979. 6. Shestakov V. N. Aortic stenosis. Internal illnesses. Ed. B.I. Shulutko. St. Petersburg, 1994, p. 66. 7. Edwards JE Calcific aortic stenosis / Circulation, 1962, 26, 817. 8. Bierman EL Atherosclerosis and other forms of arteriosclerosis // Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Hill Book Company, 1987, p. 235. 9. Friedberg CK, Sohval AR Non-rheumatic calcific aortic stenosis // Am. Heart J. 1939 vol. 17 p.m. 452. 10. Karsner HT, Koletsky S. Calcific Disease of the Aortic Valve. J. P. Lippincott, Philadelphia. 1947. 11. Hultgren HN Calcific disease of the aortic valve // Arch. Path., 1948, vol. 45, p. 694. 12. Poller DN, Curry A. et al. Bacterial calcification in infective endocarditis // Postgrad. Med. J., 1989, vol. 65. No. 767, p. 665. 13. Fernandez AL, Montero JA Osseous Metaplasia and Hematopoietic Bone Marrow in a Calcified Aortic Valve // Tex. Heart Inst. J., 1997, 24/3, p. 232. 14. Braunwald E. Valvular heart disease / Heart Disease. Ed. by E. Braunwald - WB Saunders Company, 1988, p. 1023. 15. Roberts WC, Perloff JK Severe Valvular Aortic Stenosis in Patients Over 65 Years of Age // Am. J. Card., 1971, vol. 27, p. 497-506. 16. Logeais Y., Leguerrier A., Rioux C. et al. // International Symposium on Surgery for Heart Valve Disease. Londres, 1989.